Pick up and play? The Castle of Cagliostro: Studio Ghibli’s first video game

Review Overview

Colourful visuals

8Fast pace

8Fun characters

8David Farnor | On 03, Dec 2014

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

Cast: Yasuo Yamada, Kiyoshi Kobayashi, Eiko Masuyama

Certificate: 15

Watch The Castle of Cagliostro online in the UK: Netflix UK

In the 11 days running up to Studio Ghibli’s first ever Blu-ray box set, we look back at the films of Hayao Miyazaki and what makes them so magical.

In 2013, Studio Ghibli surprised fans by providing the animations for RPG Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch. Their first video game, though, arguably came 35 years earlier.

The Castle of Cagliostro is notable for many reasons. It’s based on a manga; it directly inspired Walt Disney’s films (Cagliostro’s clock tower sequence is echoed in The Great Mouse Detecive); and, of course, it’s the directorial debut of Hayao Miyazaki. Perhaps its most striking quality of all, though, is how seemingly unlike the rest of Miyazaki’s work it is. Placed in the context of Studio Ghibli’s box set of the director’s 11 films, the 1979 flick sticks out like a sore thumb wearing 3-D glasses.

The Castle comes hot on the heels of Hayao’s work on the anime TV series Lupin III, which was, in turn, based on Monkey Punch’s manga. The second feature-length spin-off for the titular gentleman thief, Arsene Lupin, Miyazaki takes our lecherous fellow and turns him into a more conventional hero: a figure closer to James Bond than a sneaky stealer.

Of course, the word “hero” is already ringing alarm bells. One of the most recognisable traits of Miyazaki’s work is his use of female protagonists; women or girls who are defined by their actions, emotions and beliefs rather than by their appearance. Kiki’s Delivery Service is about a girl becoming independent in a new town. Spirited Away follows the coming of age of Chihiro. Even in Porco Rosso, another Miyazaki film about a male protagonist, we meet aviation engineer Piccolo, who wins respect through mechanics rather than make-up. In an age of Hollywood testosterone, Hayao’s work is a breath of fresh air.

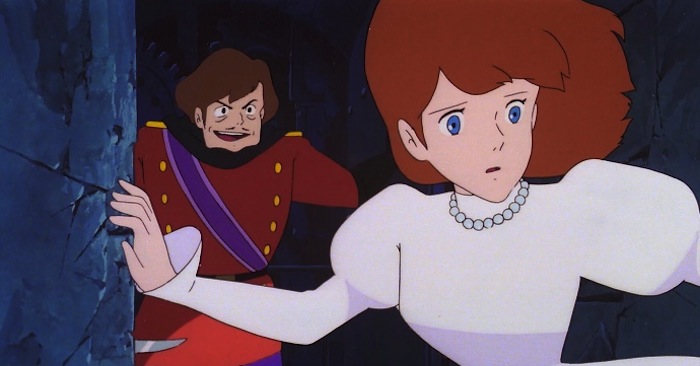

Rewind to The Castle of Cagliostro, though, and that trait doesn’t seem to have developed yet. Within the first five minutes, it’s made clear that we are following the old-school formula of man saving woman, as Lupin and his sidekick, Jigen, get caught up in a car chase with some goons, trying to rescue Clarisse, who is soon to wed Count Cagliostro. The opposite of the rescue scene later found in Kiki, where a woman saves the man, it’s made even clearer that depth is not on the cards for Cagliostro’s wee lass.

“We don’t even know why they’re chasing her,” notes our wolfish hero, with his bright tie and arrogant charm. “So who do we help?” “The girl,” replies Jigen. “Good enough,” nods Lupin. And the action begins.

A car chase? A male-driven adventure? A damsel in distress? If these are traits more akin to a video game than a Miyazaki movie, it’s perhaps no coincidence: the Lupin franchise spawned a LaserDisc computer game, Cliff Hanger, which used footage from The Castle of Cagliostro for its cut scenes, although the story itself was altered.

Why change the narrative at all, though? The Castle’s simple, yet effective, mantra – stop the bad guy, unmask his conspiracy to counterfeit global currencies and get the girl – is ready-made for a console outing.

The level design is superb (the Count’s vast Italian castle is beautiful) and practically everything on screen has a hidden trap door. Even the car chase, which sees our hero drive up the side of cliffs to get ahead of the competition, shooting tyres and dodging explosives, could be straight out of an anime version of Mario Kart. Everything about The Castle of Cagliostro, from the cocky, Indiana Jones-like lead to the simple story, begs you pick up a controller.

That’s perhaps the most defining quality of The Castle of Cagliostro: it moves at a breakneck speed, set piece after set piece, willing us to run and jump – and grapple and drive – to progress.

Such pacing would later become alien to the director. In an interview with Roger Ebert in 2002, just after making Spirited Away, he described his approach:

“The time in between clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it’s just busyness, but if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb.”

Make no mistake: The Castle of Cagliostro claps like a seal on steroids. It doesn’t worry about waiting to explore characters or find depths. After all, like a game, viewers can always pause and save when they need a breather.

Like Cagliostro’s director (and animation), though, computer games have matured since 1979. They are increasingly considered an art form now, albeit a young one, that is gradually moving away from brainless shooting and button-bashing to something more substantial. Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead, for example, is entirely about making difficult decisions to stay alive, with each choice you make dictating how events unfold. Other games are written by people such as David Goyer (Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight trilogy) and Stephen Gaghan (Traffic). Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, meanwhile, stars a motion-capped Kevin Spacey as its antagonist, with the actor helping to develop the narrative and character during production.

And, of course, there is Studio Ghibli’s contribution to Ni No Kuni. A stunning piece of design, their storytelling turns what could be a generic fantasy about a boy chosen to save a parallel universe into something genuinely moving. The opening sees our young hero’s mother lost, a tragic narrative that unfolds through regular, patient interruptions to the controller pad action – a game of “ma” rather than hyperactive applause.

And yet, even in 2014, with Miyazaki retired, the gaming industry continues to struggle with its representation of women. It’s interesting to note, for example, that Ni No Kuni has a male protagonist. Those who highlight these tropes, such as feminist critic Anita Sarkeesian, are bombarded with violent threats and sexual harassment. There are exceptions – see Clementine in Season 2 of Telltale’s zombie series – but the contrast between contemporary video games and Hayao’s later work (a juxtaposition also echoed by Studio Ghibli and Hollywood’s mostly macho output) makes you appreciate just how much the filmmaker has grown from his debut.

“If you want to shoot him, you’ll have to shoot me too,” threatens Clarisse at one point, putting herself in jeopardy to protect the man she has inevitably fallen in love with. But even that act of agency only reinforces her role within the story as a mere “treasure” to be possessed. “I’ll become a thief, just to be with you!” she later declares to Lupin, willing to lose her princess identity altogether for the sake of some male validation.

And yet there is undeniable enjoyment to be found in these formative hand-drawn frames. Approach The Castle of Cagliostro hoping for a fully-formed masterpiece and you may well be disappointed. Pick it up and play and you will be entertained no end. There are many proto-Ghibli elements to be spotted during each repeat gaming session, from Miyazaki’s wondrous flair for architecture and natural landscapes to his visual sense of humour and burgeoning style. Most of all, though, it is his sheer imagination that wins you over: a glance at the movie’s storyboards (included on the Blu-ray) shows you just how much detail his brain constantly throws up on screen in each frame.

“Cliff Hanger!” shouts the Cagliostro video game trailer. “A game to keep you on your toes and keep players hanging in there!”

That same thrill would eventually be expressed by Miyazaki through characters and creativity rather than blokes rescuing dames, but as the film’s conclusion finally slows down between claps to admire the stillness of a sunken city, The Castle of Cagliostro offers a glimpse of Miyazaki already levelling up for his next project. The result isn’t just a likeable thriller, but a demo for a magnificent career.

The Castle of Cagliostro is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.