Narratives of war: The conflicting adaptation of Howl’s Moving Castle

Alex Clements | On 01, Apr 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our review archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2014.

“It’s a battleship, looking for more cities to burn,” says the titular wizard in Howl’s Moving Castle, looking across a field of flowers towards the vast flying war machine.

“Is it the enemy’s or one of ours?” asks Sophie, a young girl with a curse that has turned her into an old woman.

“What difference does it make?” replies Howl, before a wave of his hand brings the whole thing crashing down.

At the start of Hayao Miyazaki’s ninth film, the build up to the war looks worryingly familiar: infantrymen with dashing moustaches and crowds waving garish flags, as brown and grey tanks and warships (of both the flying and sailing kind) head off to glory. Everyone is excited, and there is very little anxiety about this. People are more scared of wizards like Howl and his old enemy, The Witch of the Wastes.

© 2004 Nibariki – GNDDDT

When she curses Sofie, it’s easy to think that this will be a familiar story, the kind of quest where the young, beautiful man – and Howl is defined, in part, by his beauty – must defeat the ugly woman to save the heart of the pure girl. But as the war progresses and we learn more about everyone’s respective curses, who the enemy is becomes harder to see clearly.

Make no mistake: if you’ve read Diana Wynne Jones’s book of the same name and loved it (the only possible response to such a beautiful, elegant story) and are hoping to see it turned into glorious Ghibli animation, then you might be taken by surprise. The characters are all there in this adaptation and some plot points are kept, but everything is shuffled. Jones herself wrote one of the most insightful pieces of criticism of the film in an interview published in the last edition of the novel before her death in 2011.

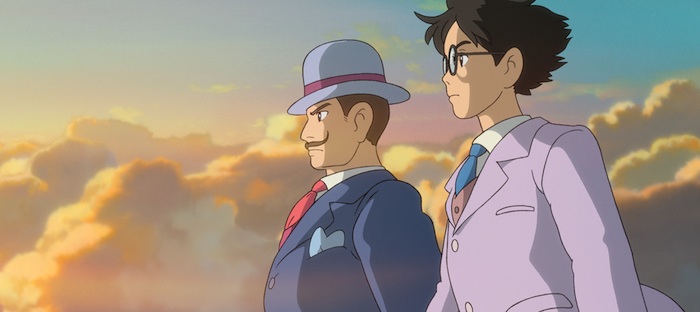

The author said that she and Miyazaki both grew up with the Second World War as a background and developed a similar distaste for war. While she decided to create fiction that had nothing to do with it, Miyazaki’s obvious fascination with the technology of war meant that, even in an ostensibly anti-war work, it was like trying to have his cake and eat it. Maybe this was ringing in his head when he set out to make The Wind Rises, his final film.

The war machines and Howl’s titular castle truly are beautiful in their industrial ugliness. They also don’t quite fit into the fairytale world. Perhaps this incongruity was intentional, but if one looks at Miyazaki’s earlier work, Nausicaa and The Valley of the Wind – especially his manga that pre-dates it – one realises that he’s drawn all these contraptions before. The insectile fliers that fit into Nausicaa’s world effortlessly seem a little more patchwork in Howl.

“But remember this, Japanese boy… airplanes are not tools for war” – The Wind Rises

© 2013 Nibariki – GNDHDDTK

The story ricochets from domestic charm to the the firebombing of civilians with little concern for foreshadowing or information dumping. Much of the magic is so familiar from fairy tales that most viewers don’t need signposting. And we all know the narrative of war, although it is rarer than you’d think to see a civilian perspective on the air-raids and warships scuttling, as they come burning into port. It gives Howl’s Moving Castle a dreamlike quality, which some people might find frustrating, but just seeing the world and being with these characters is almost so engrossing that one doesn’t need to know about the geopolitics and battle reports.

Almost, almost…

Because of this conflicting adaptation, Howl’s Moving Castle has arguably one of the most deeply unsatisfying endings of any film in the last 10 years. It is so abrupt, so jarringly convenient, that revealing it would hardly count as a spoiler because the only thing that leads up to it is a single sentence said by an unseen character in the background of the first scene. The process from parades to refugees displaced by war, from Sofie’s curse to cure, and Howl’s entire emotional development, is about growing up and facing the world as it is. It’s about the loss of innocence of individuals and populations. The ending, in under five minutes, takes all the grief and loss and death visited upon the world by distant, power hungry rulers, ties it up in a pretty little box with a pretty little bow, and ignores it.

It is infuriating. It is insulting to the character of the film. As a result, it is a dissonant note in Miyazaki’s filmography. That is telling in and of itself, of how much we expect from the director. Failing to stick the ending of something otherwise well above the normal standard for a “good” film feels like a huge let down.

© 2004 Nibariki – GNDDDT

The question is, then, with such a bad conclusion, why watch Howl’s Moving Castle? There is nothing in it that one cannot find in Miyazaki’s other work. The war machines are in Nausicaa and Laputa. Howl himself is very reminiscent of Haku, the dragon boy from Spirited away, as are many of the wizardly creatures. But of course, of course it’s worth watching. It’s just not worth watching before you’ve seen all of his other films.

Howl’s Moving Castle is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.