Simple, not simplistic: The joy of childhood in Ponyo

Philip W Bayles | On 01, Apr 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our review archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2015.

“Is someone different at age 18 or 60? I believe one stays the same.”

― Hayao Miyazaki

There’s a very fine line between a movie made for kids, and one that just happens to be a kids’ movie. The former can be a terrible thing, full of condescending dialogue and puerile toilet humour, like every Shrek movie after the first one. The latter is a thing of enthralling, transcendent beauty, that makes an 80 year-old feel like they’re eight again without talking to them like they’re eight. And nobody does it better than Hayao Miyazaki.

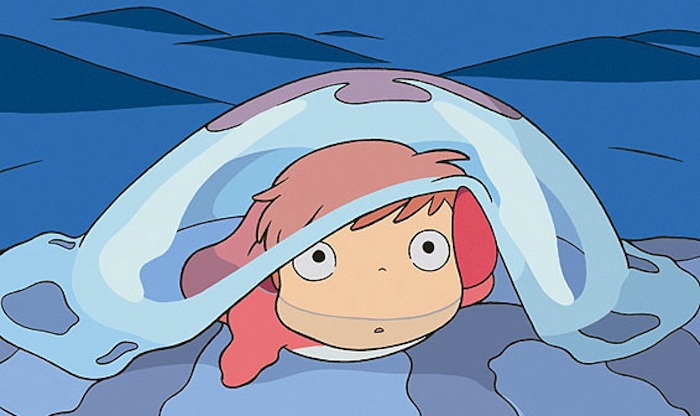

Ponyo is arguably Miyazaki’s most child-oriented film, even more than the likes of Spirited Away or My Neighbour Totoro. The rolling waves and pastel hills of the seaside town in which it takes place – to which the director himself contributed 170,000 images, the most of any of his films – look softer than usual, almost like illustrations in a children’s’ book. The story of a young girl from an undersea kingdom who dreams of becoming human to be with a boy she loves is simple and (for western audiences) highly familiar. There are nods here to the Japanese legend of Urashima Taro, a fisherman who spends 300 years at the bottom of the ocean, but the most obvious frame of reference here is The Little Mermaid – the 1989 Disney movie as much as the original fairytale by Hans Christian Andersen.

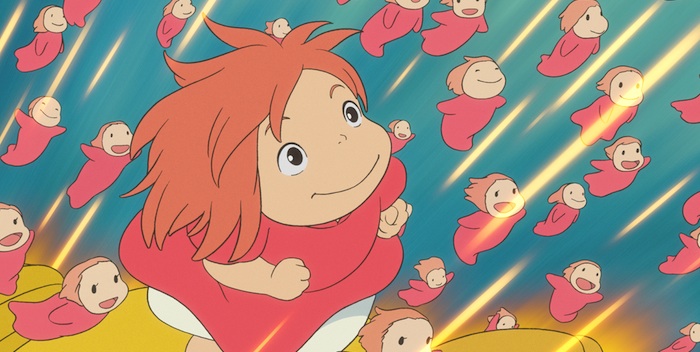

But this isn’t just a story for young children; it’s also about them. Ponyo’s age is never stated, although she is clearly pre-pubescent, and her human friend Sosuke is five years old; the youngest protagonists of any Ghibli film, with the exception of Totoro’s Mei (aged 3). But whereas the girls who meet Totoro react to the supernatural creature with surprising unflappability – even going so far as falling asleep on his tummy – Ponyo herself is a perfect representation of the completely unfettered emotion one can only feel at the age of five.

© 2008 Nibariki – GNDHDDT

Only a five year old could love another human being after meeting them for only an hour, or express the same love for ham after roughly the same amount of time. Only a five year old could look at a mug of hot milk and honey or a pot of noodles like they were ambrosia and nectar sent from heaven. And consider Ponyo’s parents: her father Fujimoto, a scientist presented as a magician in pinstripe suits who prepares magical potions; her mother Granmamare, a huge spirit who may or may not represent the ocean itself that Ponyo even describes as scary. Not every child starts life as a magical fish, but surely we all see our parents the same way she sees hers, omnipotent and scary, able to do (almost literally) anything? It’s certainly a much truer portrayal of parents as seen by their kids than we get in Totoro, where the father is a floating entity and the mother is confined to a hospital for most of the film’s runtime.

What’s more ambiguous, and more interesting, is the film’s presentation of how humans interact with nature – specifically, marine life. One would imagine a Miyazaki film set under the sea to cast a bleak light on humanity’s treatment of the ocean and, for a while, it looks as if it’s going that way. No sooner has Ponyo left her father’s watchful gaze than she is trapped in a glass jar amid a pile of sludge being dragged across the bottom of the ocean. Fujimoto, who has turned his back on the “disgusting” human world, is preparing to flood it with a multitude of aquatic creatures not seen since prehistoric times. But this is not the machination of an evil genius – he is merely trying to make a better world for his children. Again, everything comes back to the kids.

On the surface, meanwhile, the people of the seaside town may not be in total harmony with the ocean – diesel-powered boats and generators are commonplace – but it is an integral part of their lives. Sosuke’s mother Lisa weaves her little car in and out of the dry harbour every morning past hulking great ships coming in to dock. It also refuses to shy away from how dangerous coastal towns can be; given the catastrophic events in Tohoku three years later, the scenes of the oncoming tsunami seem strangely prophetic in hindsight. Yet the characters overcome these adversities and get on with their lives remarkably easily – after all, as Lisa reminds Sosuke, their house is a beacon to the ships out at sea.

© 2008 Nibariki – GNDHDDT

However, there’s a bizarre paradox hiding at the heart of Ponyo – while it sweats the small stuff the way most young children do, it presents the really meaty arcs of the narrative with an indifference bordering on the blasé. Sosuke’s father spends the majority of the film stuck out at sea, yet when the tsunami hits, it’s a long time before anyone even addresses the question of whether his ship might have sunk. We learn from Fujimoto that if Ponyo’s magic doesn’t keep her human she will turn to sea foam (a macabre aspect of the mermaid story that Disney wisely chose to cut) and yet this turns out to be nothing more than a passing remark, never mentioned again. Perhaps this is Miyazaki taking a subtle dig at Hollywood’s tendency to add tension for its own sake. After all, given Sosuke’s actions, his love for Ponyo is hardly in doubt. But alongside the importance he bestows on other scenes of the film, it makes for an oddly uneven tone.

While Ponyo may not be the most narratively accomplished of Miyazaki’s movies, though, it still serves as a shining example of something many family oriented films still fail to grasp: the difference between being simple and being simplistic, between being childlike and merely childish. Just because kid’s tastes aren’t as refined, it doesn’t mean they don’t deserve to be told genuinely great stories. And Ponyo, despite its flaws, is certainly one of those.

Ponyo is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.