Miyazaki’s motto: Living for art as The Wind Rises

David Farnor | On 01, Apr 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our review archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2015.

“The wind is rising! We must try to live!”

That quote heralds the final film of Hayao Miyazaki. The director, whose career spans over five decades, has enchanted kids of all ages with his unique brand of animated magic. It might seem surprising, then, for his work to end with a distinctly adult tale, but The Wind Rises – a fictionalised biopic of aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi – reveals itself to be a personal history, as much as a national one.

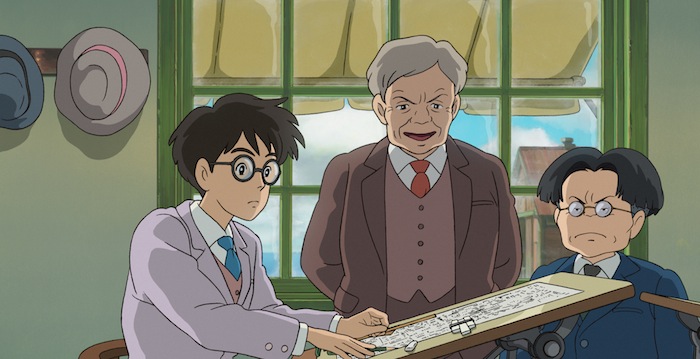

Like many of Miyazaki’s protagonists, Jiro longs more than anything to fly. He dreams of being a pilot, a hope that is quashed by his imperfect eyesight. And so he decides to build planes instead, poring over blueprints and complex sums to create a flawless craft.

It’s not hard to imagine a young Hayao doing the same – even without his obsession with planes cropping up everywhere from The Castle of Cagliostro to Porco Rosso. The director’s love of soaring, by magic, manufactured objects or otherwise, has gifted the childlike maestro with some of his most memorable and dazzling moments, ones that, like Jiro’s work, took hours of dedication and detail to bring to life. In the case of Ponyo alone, that hand-drawn approach saw Hayao himself contribute 170,000 odd images to the project.

As Jiro slaves away to bring his vision of the Zero fighter into being, he travels the world (visiting Germany to gain inspiration from their designs) and even falls in love. The latter occurs as the Great Kanto Earthquake strikes in 1923, causing him to help out a young girl (Nahoko Satomi) and her mother on a derailed train. Years later, when they are reunited by chance, it seems only natural that they should end up together, especially when she falls ill, leaving Jiro torn between looking after her and caring for his other, airborne baby.

Love – and, particularly, devotion – crops up frequently in Miyazaki’s work, often tied to the importance of nurturing nature. That message informs the filmmaker’s keenly pacifist stance (he was born in 1941, the year that the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor) and this ethical concern becomes a central dilemma for Jiro. The engineer wants to build the perfect plane, a vision that is thrown off balance by the addition of guns to the wings; he sees his vehicles as art, not instruments of war.

As WWII descends, though, Jiro finds himself once again torn over his work. And yet he keeps going, honing theories, devising new ways to reduce wind resistance. All the while, he dreams of Caproni, his Italian aviation inspiration, a moustached man with vivid proclamations about life, ambition and airplanes.

These literal flights of fancy aside, though, The Wind Rises is notable for its down-to-earth realism compared to many other Studio Ghibli adventures. Heartbreak, poverty and cigarettes all make an appearance – things you would never see on your typical Catbus commute.

It’s tempting, therefore, to see The Wind Rises as a reference to what the world throws at us. Earthquakes sweep casually across the screen like rain rolling on the breeze, a natural force buffeting our existence, as we struggle to carry on. The wind is rising! We must try to live!

But Miyazaki’s swan song shows us the other side of the drawing board. Jiro gives up hours, days, years to his work – the film spans several decades, the most epic scale of any Ghibli movie, despite taking place in offices and tiny bedrooms, rather than lush forests or hovering cities. The rest of it, Jiro squeezes in when he can.

“Beautiful! Look at that curve!” he exclaims, as he goes to eat lunch with his colleague (whose attitude towards planes and war is far more pragmatic). “Only you would get a thrill from a fish bone,” comes the dry reply.

There is a clear contrast between mother nature and machinery – oxen drag ships out to runways ready for testing, echoing the environmentalist leanings of Hayao’s previous films – but through Jiro’s eyes, they blend into the same thing. Miyazaki shares that view. Here, as in many of his animations, the metal contraptions seem to pulsate rather than move; the pencilled edges wobble and breathe, while “Whish! Whoosh!” noises (provided, tellingly, by the voice cast) pitter and patter over the top.

That same thrill is even felt from Jiro’s drawings; the film’s most bravura sequences see his sketches leap off the page and dive and swoop as fully-formed things.

“Oh, she’ll fly,” he tells his colleague. “I feel the wind rising.”

The wind of inspiration is what drives our hero, a man whose ideas float in unexpectedly, only to blow everything else off the table. The struggle, really, is trying not to forget the rest of his adult life.

But it’s not just Jiro’s seemingly limitless creativity that astounds; it’s his ability to convey it to others. A whole room buys into his hypothetical concepts; his imaginary planes are seen hovering by everyone around him.

“That was interesting,” says one of his bosses, after a meeting. “It was inspiring!” says the other, his hair flapping like wings, as they stroll down a corridor.

There are traces of the director’s other themes and concerns – “Men have it so good,” scoffs Satomi, with a hint of the feminism that has given Ghibli an unparalleled run of female leads, while Joe Hisaiashi’s music is typically beautiful – but it’s in this final, atypical entry that you sense Hayao Miyazaki the most. In the endless rustling of his pages, and in his ability to share that imagination with audiences.

“Artists are only creative for 10 years,” Caproni tells Jiro, in a dream towards the end of the movie. “We engineers are the same.” Even if the film’s assertion is true, that an artist’s creations are tied to the period in which they’re made – planes hijacked for war, rather than for peace – after 50 odd years, Hayao’s own career (and its ongoing influences) defies the message’s apparent gravity. The master may be retired now, but his imagination continues to soar. The wind rises. We must try to live.

The Wind Rises is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.