Astonishment and empathy: The magic of Studio Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki

Nathanael Smith | On 30, Jan 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2014.

Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary animator celebrated by a Blu-ray box set out in time for Christmas (Monday 8th December), once unwittingly summarised the appeal of his films in an interview with Roger Ebert. “If you stay true to joy and astonishment and empathy, you don’t have to have violence and you don’t have to have action. [Children] will follow you. This is our principle.”

While only some of his films do have violence and action – surprising amounts of it, in Princess Mononoke – every single one of them is characterised by joy and astonishment and empathy. That he combines such rare storytelling traits with the technical skill and creative élan of cinema’s historical greats is what makes him not only one of the greatest animators of all time, but also one of the greatest directors.

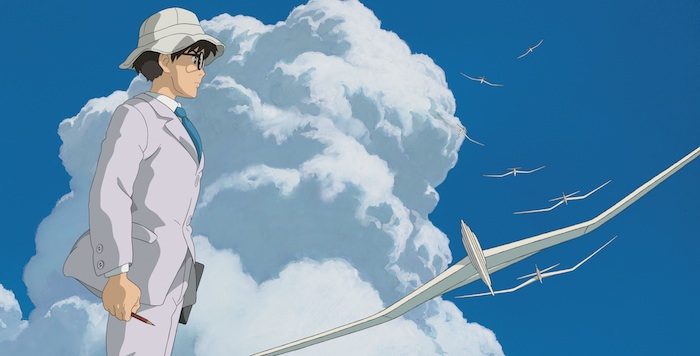

Miyazaki’s most distinctive quality, his vivid and unparalleled imagination, was present from his debut feature, The Castle of Cagliostro. Starting out in 1979 with this pacy adventure of dashing thieves and crumbling castles, the then young upstart established himself as a fiercely creative mind, injecting a formulaic princess-trapped-in-a-tower plot with as much visual verve as possible. Cars don’t turn, they careen (bad drivers are a recurring theme in his films), while the final action sequence takes place inside a clocktower, a scene so thrilling that Disney would homage it only a few years later in Basil: The Great Mouse Detective. His last film, 2013’s The Wind Rises, has invention spilling equally out of the frame, even though it is ostensibly his most realistic film. Whether in the gorgeous dreams of flight that punctuate the story, or in the way the earthquake is depicted as a series of waves swelling beneath the earth, the brightness of the man’s mind remains undimmed by non-fiction. And those are the only two films in his canon that couldn’t be classified as a fantasy – the rest of his work is even more dazzlingly inventive.

Kiki’s Delivery Service

© 1989 Eiko Kadono – Nibariki – GN

One touchstone for this invention seems to be Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, most evident in the rabbit-hole and Chesire cat homages in My Neighbour Totoro, but twinkling behind every reel of his films. Just as with Carroll’s capacity for the absurd, Miyazaki uses fantasy to let his imagination run, unrestrained, across the celluloid. Who else could have imagined the grotesque denizens of the bath house in Spirited Away, or the robot gardeners of Laputa: Castle in the Sky?

Carroll and Miyazaki both love children, and their work exists to bring joy to the younger generations, yet what Miyazaki also manages with his films is to make the audience – children and adults alike – see the world in a new way. Consider the way Kiki flies haphazardly through the town in Kiki’s Delivery Service; he uses flight in this, as with Porco Rosso and The Wind Rises, to view his world differently, whipping through it at great speeds and from a number of different angles, above, along and upside down. With Kiki, however, he also shows it to us through the eyes of a child, as big and scary as it is exciting. By adding the one fantastical element of a young witch to an otherwise real world, the familiar and the strange collide in a way that exactly captures the astonishment he aims for – something he succeeds in doing with each one of his films.

Part of the enduring appeal of Alice in Wonderland, however, is the heroine herself: curious, intrepid and strong-willed – a description that could easily fit most of Miyazaki’s leading ladies. Mei and Satsuki in My Neighbour Totoro bicker and cry, like most children, yet they are also characterised by vibrant imaginations and a strong sisterly bond. Nausicaa is a warrior princess who leads her people with wise judgement, yet still finds the time to be curious about the toxic jungles that line the edges of her world. Sophie in Howl’s Moving Castle, Chihiro in Spirited Away and Sheeta in Laputa are all equal parts naïve and principled, and all of them have character arcs that too few live action films can muster for women. Miyazaki is unafraid to show their complexities and vulnerabilities, proving that such traits are not mutually exclusive to ‘Strong Female Characters’. The consistency with which he writes believable and inspirational female lead roles frankly puts the rest of cinema to shame.

Spirited Away

© 2001 Nibariki – GNDDTM

Alongside the thrill of his imagination and the richness of his writing, the third major characteristic of a Miyazaki film is the craftsmanship of the animation. His films are instantly recognisable, combining fairly plain character animation with lushly detailed backgrounds that display a hushed reverence for the power of nature – accompanied by the always excellent Joe Hisaishi, his composer and collaborator. Not only are they beautiful works of art, bursting with colour, but Miyazaki also directs as if the artists were cameramen, not simply content to depict a scene, but to shoot it, making them intensely cinematic.

There are any number of scenes that could be used to illustrate the skill and flair of Miyazaki’s style: the opening dream of The Wind Rises; the trumpet wake up call in Laputa; the flashbacks in Nausicaa; every single moment of Howl’s Moving Castle or Spirited Away. Yet it is, perhaps, best to appeal to his most iconic scene, featuring a bus stop, two sisters and a Totoro. Lit with a single streetlamp, and beneath the rain of a Kurosawa movie, the three unlikely companions bond over the sound of raindrops hitting an umbrella. Cutting between wide shots and the reactions of each character, plus a passing frog, the scene juxtaposes the mundanity of waiting for a bus with the magic of the everyday, one of Miyazaki’s great skills.

Every shot is perfectly judged, from the way a raindrop causes a branch to sag, to the way the circle of the lamp light crosses over with the patterns on Totoro’s chest, to the way the camera looks upwards to the grinning spirit’s face. It’s a moment of pure cinematic magic.

My Neighbour Totoro

© 1988 Nibariki – G

Miyazaki once described his determination to use hand-drawn animation as “like rowing in a sea full of speed boats”, and his public defence of the art form makes his retirement an even bigger blow to fans of the medium. It seems as though hand-drawn animation, like black and white cinema and anything in academy ratio, will be consigned to art house cinemas, wholly replaced without much choice by the unstoppable homogeneous force of computer animation. Obviously, there are some real binary artists out there who can create beautiful images and compelling stories from the most cutting edge technology, yet there is something ineffably different about the magic of hand-drawn animation, and Miyazaki was the master of it. Beneath his brush, earthbound humans realised they could fly, children learned to imagine and create, and his audiences have been on the most unforgettable journeys, lost in a sense of wonder that is impossible to replicate anywhere else.

Which brings us back to the joy, astonishment and empathy that the man himself prizes so much. His films are exuberant, brightly lit, and behind all the fluffy forest spirits and flying pigs, exceptionally human. The commitment to these principles has so clearly guided his choices that his collected work is perhaps more cohesive and recognisably his than that of any other director.

Many film makers have at least one film in their catalogue that they are less proud of, or was compromised by studio interference, or doesn’t seem to fit in their canon quite so well – Spartacus, Alien 3, half of Spielberg’s recent output. Not so, Miyazaki. 11 films form a perfect canon, with the sheer, unrestrained joy of creation coursing throughout each one of them. They are all made out of love, for the people watching it and for the medium itself, and that love is evident in every single frame.

He is a director who is optimistic about the world, because he cares about the people in it.

Studio Ghibli films are available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2014. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.