Why Kevin Can F**k Himself should be your next box set

Review Overview

Cast

8Story

8Satire

8Martyn Conterio | On 04, Sep 2022

The origins of Valerie Armstrong’s AMC-backed genre parody meets existential saga are said to reside in the Kevin James-fronted sitcom, Kevin Can Wait. In the world of that show, Kevin’s wife was killed off (when the actress playing her was fired after the first season’s run) and then this harrowing and life-altering bit of news was brought up casually in dialogue at the start of Season 2, like it was no biggie. This surreal handling of death and grief inspired Armstrong’s dissection of gender politics and sitcom dynamics, and clearly its title draws inspiration directly from the Kevin James character, with a message for him – and other sitcom leads like him – delivered loud and clear.

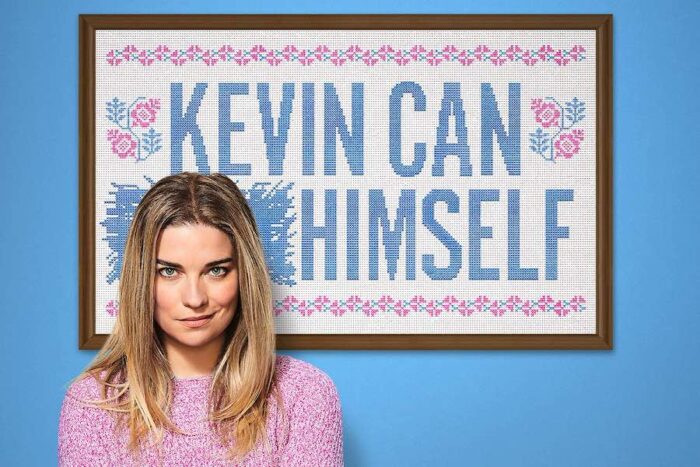

Headlined by Schitt’s Creek star Annie Murphy, Kevin Can F**k Himself tells the story of Allison McRoberts, a 30-something working-class woman from Worcester, Massachusetts. She’s married to Kevin McRoberts (Eric Peterson), a bloke who is nothing but selfish, idiotic and barely sees his wife as a person. He acts like the star of his own show, the centre of his own universe – everything is always about him, his needs, his wants, his hare-brained schemes and shenanigans are ripped straight from Sitcom 101 scenarios.

Allison’s terrible marriage is presented as a classic US sitcom: there’s the bright lighting style pioneered by legendary cinematographer Karl Freund, multi-camera shooting with a tendency towards wide shots, a big stage-like set, false backdrops, make-up, and caustic and sarcastic chatter that’s followed by a canned laughter track. As soon as Allison is removed from Kevin’s sphere, the shooting style changes completely to a single camera set-up, with realistic lighting and décor. The world around her is drab, duller; Allison doesn’t wear make-up and we see her as thoroughly miserable and defeated rather than comically exacerbated.

Allison is fed up and increasingly hostile to her husband, declaring the world is rigged in his favour and that she feels cosmically cheated out of a good life. She’s better than this, better than Kevin, but how can she change her lot? As the show is seen exclusively through the eyes of troubled Allison, it means Kevin, his best mate, Neil (Alex Bonifer), and enabling father, Pete (Brian Howe), are depicted as one-dimensional morons. But Allison to them is almost invisible; they do not take her into account or their mutual friend and neighbour, Patty (Mary Hollis Inboden). Allison sees domesticity as a torturous grind. What Kevin sees is domestic bliss. Allison is stuck in a trap, her best years wasting away.

The sitcom set-up is never explained, and rightly so. It doesn’t need an explanation because its function is psychological, satirical and thematic. It’s not some magical bump on the head or a dream-style presentation. It also works because the juxtaposition, while jarring and strikingly odd, is also bravura, always enriching the subtext and constantly feeding into the unfolding, sometimes bleak material. It captures succinctly Allison’s alienation from her own house and environment. She is powerless when existing in the sitcom, and the contrasts between realities take increasingly dark turns as she plots her escape from life with Kevin.

Annie Murphy, a comic revelation as Alexis Rose in the beloved Schitt’s Creek, proves she has more in her acting locker than playing an airhead with a heart of gold. Here she excels as a deeply frustrated and entirely flawed woman filled with murderous rage, who rebels against playing the doormat sitcom wife and is sick to death of being both like a mother and a wife to her man-child spouse. In the sitcom scenes, the look in her eyes, when heightened by the glossy aesthetic, is blackly comic. When she’s alone, her eyes register as a thousand-yard stare. We feel Allison’s despair, the suburban suffocation, the deep loneliness, and she develops into a kind of antihero. Murphy knocks it out of the park.

Eric Peterson, too, is brilliant as Kevin, the actor all-in as a thoughtless oaf, a Homer Simpson made flesh, a bloke who loves his bros and sports and male freedoms, who takes his wife for more than granted. His patronising dismissals of Allison’s numerous concerns always feed into the stifling atmosphere that builds and builds throughout the first season’s 8-episode run. In vibe, the closest thing Kevin Can F**k Himself comes to is perhaps Too Many Cooks. Allison is living her own version of that nightmarish sitcom satire, which became an internet sensation. At its best, Armstrong’s drama boasts the same cyclical weirdness and Murphy’s superlative performance ensures we are invested in Allison’s dangerous mission to break the spell.

Kevin Can F**k Himself, a drama masquerading as a sitcom, deserves plaudits – and most importantly eyeballs – for exploring and rejecting standard-issue sitcom hijinks, and for using genre parody in such a fascinating and insightful way.