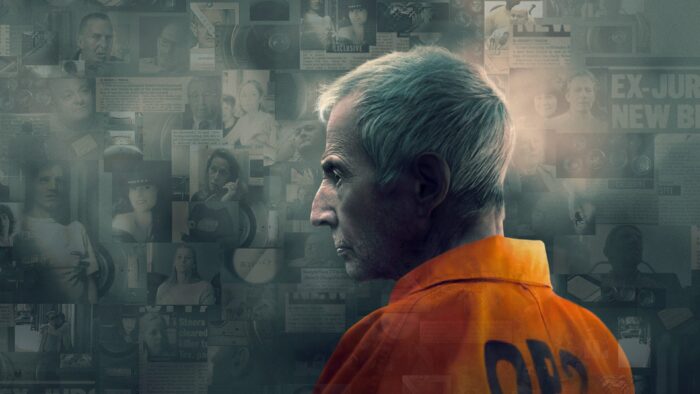

True Crime Tuesdays: The Jinx: Part Two

Review Overview

Crime

10Justice

4Entertainment

6Helen Archer | On 11, Jun 2024

Almost 10 years have passed since the release of The Jinx, Andrew Jarecki’s game-changing true crime series, which looked into the life and crimes of multi-millionaire real estate heir Robert Durst. That series opened with the allegations that he had murdered his friend and neighbour Morris Black in 2001 in Galveston, Texas, but soon jumped back in time to the disappearance of his first wife, Kathleen McCormack, in 1982, and the murder of his close friend and confidante, Susan Berman, in 2000. Durst volunteered to take the hot seat to be interviewed about it all after Jarecki made the 2010 film All Good Things, which was a loose adaptation of the Durst marriage. Presumably, Durst hoped the documentary would clear his name. In fact it had quite the opposite effect.

Durst’s hot-mic moment in the closing of the first season, in which he mumbled to himself during a bathroom break ‘killed them all, of course’, was something of a seminal moment in the genre of true crime – a filmed confession, of sorts, albeit an unintended one. Part Two spans the years from 2015 to Durst’s death in 2022 and beyond, and opens the day before the Season 1 finale aired on HBO, as Durst is arrested – thanks, in part, to the content of the series – and a viewing party congregates to watch, for the first time, that final episode. Gathered together are the victims’ family and friends, and various Durst associates, and the mood of the party turns from buoyant to stunned silence as the episode ends.

It’s almost symbolic of the way in which the viewer interacts with this series as it goes on. While the viewing party seems in retrospect fairly crass, so too do the various contributors who gush about how “entertaining” Durst is, even at his most sociopathic. Lawyers, interns and assistants, Durst’s “friends” (most of whom are bought and paid for, including a man who served as a juror in one of his trials), journalists, and so on can’t help but talk about him in a somewhat flippant manner, perhaps imitating the interviewing style – cajoled into telling stories that they perhaps don’t realise how poorly they reflect on them. It all makes for rather uncomfortable viewing, in which the audience feels vaguely complicit in this true crime as entertainment.

Much of it is a tawdry tale of the greed and amorality of those who surrounded Durst, and the lengths they would go to protect him – and, therefore, their income streams. Durst himself is less of an occasionally charming enigma and more of a chilling psychopath – perhaps because we know more about him now, perhaps because we are more used, as viewers, to being more suspicious, less easily charmed. It all culminates in an episode that focuses on Durst’s widow, Debrah Lee Charatan, the woman who profited most from her association with Durst. The privileges that shield the elite from any consequences for their behaviour are exposed, although sadly not defeated.

It is something of an unsatisfying ending, given that, for most of his life, Durst evaded justice, and that Charatan was – and is – financially rewarded. It is, though, an ending to the story of Durst – a story that would doubtless not have come to public light had it not been for the years-long work of the show’s director and creator. Perhaps it is, too, an ending to that particular era of true crime, in which criminals are laughed with, chummed up to, their victims playing second fiddle to the main character. It may have worked a decade ago, but in an ever-changing world the jaunty tone seems somewhat distasteful.