The fantasy of flight: Porco Rosso and Miyazaki’s lifelong obsession

Matthew Turner | On 01, Feb 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2015.

Miyazaki’s obsession with flight is evident throughout his films. In fact, flying sequences feature in all but three of his 11 pictures (Ponyo, Princess Mononoke and The Castle of Cagliostro are the exceptions). Flight, in general, is often central to the plot, most notably in 2014’s The Wind Rises (about an aviation engineer) and 1992’s wonderful fantasy Porco Rosso, about a flying pig.

It’s not hard to see how the magic and wonder of flight worked its way into Miyazaki’s childhood imagination – both his uncle and his father were involved in the aviation industry and the latter was director of Miyazaki Airplane, which made rudders for Japanese fighter planes during World War II. However, it’s not just the spectacular visuals that made an impression on the young Miyazaki – he also developed a passionate interest in the technical details of flight design, perhaps as a result of being surrounded by conversations between aeronautical engineers for most of his early life.

Both Porco Rosso and The Wind Rises contain scenes with characters poring over blueprints and excitedly discussing specifications and improvements in a way that emphasises their creativity and inspiration. To Miyazaki, then, flight is a feat of technical engineering that produces something close to art; the details are meticulous (the importance of each rivet is noted), but the whole is something that is breathtaking in its beauty. Indeed, it could be said that Miyazaki’s approach to animation operates in much the same way.

Flight is also something that represents dreams, fantasy and imagination – in a way, it is where the fantastical invades the real world, since it’s where humans have actually achieved their dreams and made the fantasy of flight a reality. Porco Rosso is the perfect embodiment of this crossover – he’s a pilot who has been transformed into a pig, the only fantastical element in an otherwise realistic film.

The movie takes place during the inter-war years (in or around 1929, as evidenced by the date glimpsed on Porco’s film magazine) and is set in the Adriatic Sea, between Italy and the former Yugoslavia. Porco Rosso himself is an ex-WWI flying ace (his name, the Italian for “Red Pig”, is perhaps an allusion to The Red Baron), who now makes a living as a freelance bounty hunter, taking down air pirates, such as the heavily bearded Mamma Aiuto (meaning “Mummy, Help!”) gang.

© 1992 Nibariki – GNN

Alhough he flew during the war as a fighter pilot named Marco Pagot (named after an Italian animator), Porco has since been transformed into a pig, through a magic spell or curse that the film never clearly defines. However, it is suggested that the curse is in some way self-inflicted, either through Porco’s disillusionment with the human race or through survivor guilt, after he witnesses the deaths of many fellow pilots.

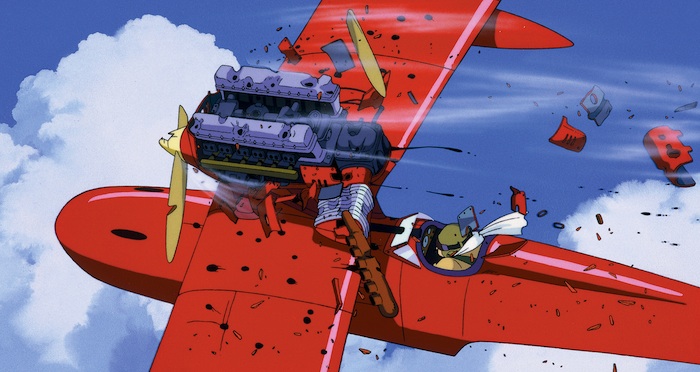

The plot itself is relatively simplistic. Shot down by Curtis, an American pilot who’s working for the pirates, Porco travels to Milan where his plane is re-designed and rebuilt by Fio, the gifted grand-daughter of Porco’s loyal mechanic, Piccolo. When the pair return to the Adriatic, they are captured by pirates and Fio talks them into allowing a rematch between Porco and Curtis.

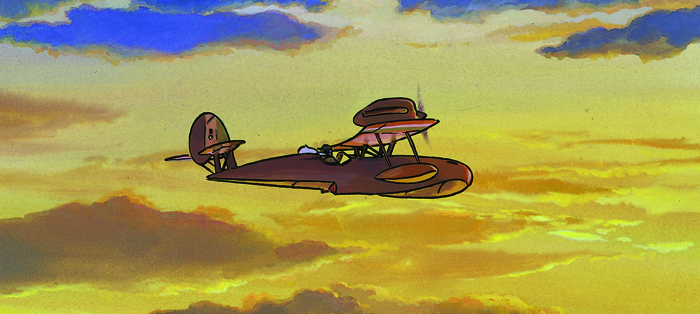

The film is, of course, packed with beautiful flying sequences, and it’s fascinating to examine the differences between them. Most obviously, there’s the thrill of the action, in particular the exciting dogfights, which contain both gunfire and aerial stunts. However, there are also more peaceful moments, such as a beautiful, leisurely sequence of Porco flying back to the mainland, soundtracked to French torch song Le Temps des Cerises, which is being sung by the Hotel Adriano’s Madame Gina (who loves Porco) to a roomful of pirates. This scene captures the serene, tranquil quality of flight, emphasised by a stunning shot of Porco’s plane framed as a tiny speck in the distance, set against a vast cloudscape.

Another breathtaking sequence occurs when Porco flies over Gina’s hotel, to let her know he’s still alive (she has already lost three pilot husbands). As his plane dips towards her, the perspective shifts to Porco’s point of view and the scenery is suddenly inverted, with Gina and the hotel grounds swirling around the screen. This shot, coupled with a later point-of-view sequence – in which the plane speeds low over the countryside, its shadow visible on the ground below, before hurtling out over the sea – captures the sheer speed and spectacle of flying, but from the pilot’s perspective; a visual thrill that appeals to both Miyazaki and his audience on a visceral level (the effect is equivalent to being on a roller coaster ride).

However, the stand-out flying sequence in Porco Rosso occurs during our porcine hero’s flashback to his combat experience in WWI, as he relates the story of how he turned into a pig to a rapt Fio. There are two stages to the scene – the first shows a sky filled with fighter planes, except rather than depict them in hellish deadly combat, Miyazaki has the planes flying around each other in almost balletic fashion, giving what should be a scene of horror and chaos a sense of astounding beauty. This is then shattered as the first of the planes (in long shot) falls away in smoke and flames.

The scene then shifts to a peaceful shot of Porco’s plane emerging from a “cloud prairie” (a flat, desert-like bed of white), as Porco says that he lost consciousness during the battle. Looking up, he sees a streak of light, which is then revealed to be hundreds of airplanes, the souls of the dead pilots ascending to the heavens. After calling out to his friends and receiving no answer, Porco sinks back beneath the clouds and later regains consciousness to discover he was the soul survivor of the vicious battle. This poignant and brilliantly under-stated sequence brings home the tragic side of flying, as well as an awareness that something so beautiful can have such deadly consequences when used in warfare.

As well as capturing both the technical detail and the physical sensation of flight (note the use of sound and visual flourishes, such as the spatter of engine oil), Miyazaki fills Porco Rosso with a multitude of tributes to early aviation. Curtis is named after American aviation pioneer Glenn Hammond Curtiss, who, along with the Wright Brothers, founded the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. Porco’s dead pilot friend, Bellini (one of Gina’s husbands), is named after an Italian pilot who was killed while attempting to set a seaplane speed record in the 1930s. Many of the planes in the film are also closely modelled on real aircraft, although Porco’s Savoia S.21 bears no resemblance to the real-life Savoia S.21 and is instead derived from a plane Miyazaki saw as a child. There are also a number of nice in-jokes, such as Porco’s engine being embossed with “Ghibli” (a real-life WWII airplane, as well as Miyazaki’s studio name).

Perhaps the most amusing detail, though, is that the film was originally conceived as a short movie designed to be shown as an in-flight film for Japan Airlines, before Miyazaki decided to expand it into a full-length feature.

Porco Rosso stands as the perfect crystallisation of Miyazaki’s lifelong obsession, capturing the technical artistry of airplanes, the visual poetry of them in action, the visceral, physical sensation of soaring through the air, and the sheer child-like wonder of seeing the fantasy of flight come to life.

Porco Rosso is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

Note: This was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.