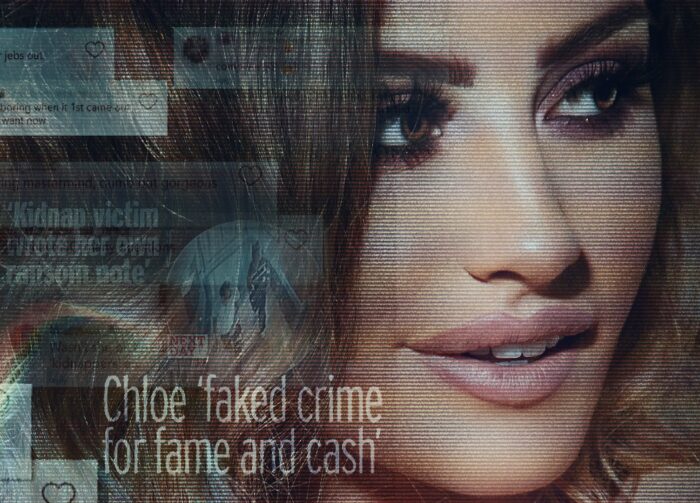

True Crime Tuesdays: Chloe Ayling: My Unbelievable Kidnapping

Review Overview

Victim-blaming

8Exploitation

7Analysis

3Helen Archer | On 19, Aug 2025

In 2017, Chloe Ayling, a fairly unknown glamour model from Surrey, travelled to Milan for what she and her then-agent thought was a photoshoot. In fact, the appointment she had made was with Łukasz Herba and his brother, Michal, who ambushed her, injected her with ketamine, and took photos of her in her underwear, before stuffing her into a holdall bag and putting her in the boot of their car. They took her to a cottage in the Italian countryside, handcuffing her to furniture and telling her that they worked for an organisation called ‘Black Death’, which specialised in sex-trafficking women and girls on the dark web.

Łukasz was the one who ‘looked after’ Chloe, pretending to protect her from the more ruthless elements of Black Death, sleeping in the same bed as her, before ultimately agreeing to release her to the Italian embassy, against the will of his alleged overlords, and on the condition that Chloe say nothing about the organisation he claimed to be working for. If this seems fantastical, it’s because it was – Lukasz had made it all up, although Chloe believed it, remaining in fear for her and her family’s lives long after she was safe.

Much of the British public first heard about all this when Chloe, having finally returned to England after a time spent in hiding in Italy, gave a statement to a gaggle of press who had been camped outside her house. Immediately judging her, both by her clothes and her demeanour, they, en masse, decided she was lying – believing instead the kidnappers’ second version of events. Łukasz, after telling Italian authorities that he was in debt to Black Death, who coerced him into the kidnap, had since changed his story, implicating Chloe in her own kidnapping – indeed, suggesting it was all her idea: a complicated publicity stunt in order to boost her profile. He was eventually convicted and sentenced to 16 years, branded a narcissist by the Italian courts, and yet his second set of lies lingered in the public consciousness, resulting in an orgy of victim-blaming that Chloe felt the brunt of, in her personal life and through the press.

Both this three-part documentary (directed by Stuart Bernard and Miles Blayden-Ryall) and last year’s six-part dramatisation, Kidnapped: The Chloe Ayling Story (directed by Al Mackay), should finally put paid to any lingering doubt, even if the verdict and sentencing did not. Chloe clearly falls into that unfortunate category of women whose behaviour somehow belies their status as true victims. In both drama and documentary, however, the viewer understands her behaviour completely – her calmness in the face of real danger saving her from further harm, and her smiling through each press appearance a form of masking, a tight control of emotions to present a public face of neutrality.

But both programmes also fall short of delving into the more institutional nature of victim-blaming and exploitation. Much more should be asked of Adrian Sington, for example, the agent who swooped in after Chloe’s ordeal, to monetise her story by throwing her to the sharks of the tabloid press and daytime TV. Though Chloe was a willing subject – unable to get work modelling thanks to the controversy surrounding her – her naivety and unworldliness made her easy pickings for the cynical purveyors of the news cycle. One journalist is interviewed in the documentary, to voice the side of those in the media who questioned her version of events. Nick Pisa states that the story was “too good to be true”, while simultaneously asserting that his profession’s obligation was to “ask questions” of the victim, rather than report on the facts. More analysis of this would elevate a sympathetic, though run-of-the-mill, series into something more thought-provoking.

Ayling herself is far more gracious in the documentary than anyone has the right to expect. Any anger at her treatment at the hands of the press and public is either successfully suppressed, or expressed through a demeanour of delicate confusion. Yet she admits that the victim-blaming did more long-lasting damage to her psyche than the kidnapping, and it is this need to be believed which forms the impetus of both drama and documentary. One can but hope for her story to spur some self-reflection in both press and public alike, even as we seem doomed to repeating the same cycle indefinitely.