Adulthood and imagination: The secret to Spirited Away’s success

Neil Alcock | On 01, Mar 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our review archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2015.

With a CV containing just 11 features as director, Hayao Miyazaki’s career is the very definition of quality over quantity. It’s impossible to pick the “best” entry from his filmography, not just because such an endeavour is based entirely on subjective criteria, but because they’re all wonderful in their own way. Objectively speaking, though, Spirited Away is the most successful: it remains the highest-grossing film of all time in Japan (unsurprisingly, Miyazaki owns four places in that particular top 10), has made more money than any of his other films, and is the only one to pick up an Oscar (Best Animated Feature, 2002).

There are countless reasons for Spirited Away’s global success, some more prosaic than others – it was the first Miyazaki to get an English language dub from the Pixar team, who treated it like one of their own – but placing it in the context of the rest of its director’s output reveals that it’s the perfect summation of all the themes about which he was most passionate. Everything Miyazaki cares about, and everything he was a master of, is woven into Spirited Away in exactly the right proportions, making it both the ideal introduction to his work and the definitive Miyazaki masterpiece.

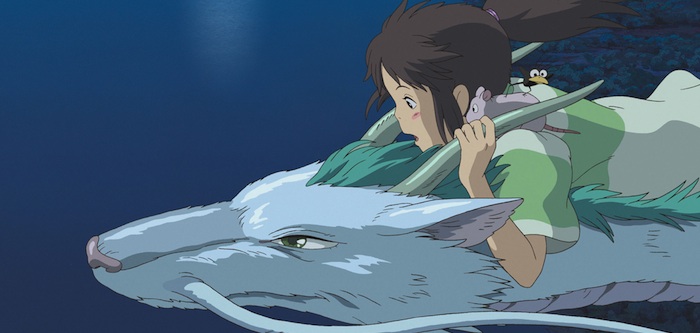

Spirited Away

© 2001 Nibariki – GNDDTM

As in Alice’s adventures in Wonderland or Dorothy’s Oz-based shenanigans before her, Spirited Away’s Chihiro undergoes an odyssey filled with enormous change,

lesson-learning and cold, hard realisation. Separated from her family during the move to a new town, she finds herself in Yubaba’s bath house, a mysterious place full of terrifying, complex grown-ups and weird concepts, where hard work equals reward and survival. The sign over the door may as well read “Welcome To Adulthood”. And like those earlier stories, as in life, Chihiro learns that adults don’t have all the answers (Yubaba’s benevolent twin sister Zeniba only nudges Chihiro towards her goal). As time goes by, she makes the transition from student to teacher, showing Yubaba’s giant baby and the childlike spirit No-Face how to be better people.

Miyazaki’s preoccupation with nature and frustration at man’s relentless destruction of it were concentrated in his previous film, Princess Mononoke. In Spirited Away, he dials his anger down without diluting the message. The disgusting spirit, who enters the bath house a stinking, rancid mass of gunk, is purged of man-made trash to reveal a pristine, smiling River God, who bestows upon Chihiro a magic dumpling she uses to cleanse her two “polluted” friends, No-Face and Haku, while Haku’s character reveal is a heartbreaking reference to the ceaseless march of industrialisation at the expense of natural beauty.

Spirited Away

© 2001 Nibariki – GNDDTM

In a similar vein, Miyazaki’s representation of greed as the most abhorrent sin is prevalent throughout. Most obviously portrayed through Chihiro’s parents voraciously troughing unearned food – only to find themselves turned into foul, oversized pigs – greed is a constant presence in the adult world. The bath house staff’s lust for gold doesn’t go unpunished, and its effect on No-Face – tainting his purity and rendering him an appalling monster – forces Chihiro to show him that acts of selflessness trump being a grotesque, all-consuming beast any day.

The old ways are the best in Miyazaki’s oeuvre, and the complex, mechanical workings of the bath house are another quiet plea for a return to tradition in Japanese culture. Chihiro’s father trumpets his car’s four wheel drive, but it doesn’t help him avoid his porcine fate; the train that carries her across the water, meanwhile, is a peaceful carriage to hope. And let’s not forget the animation itself: exquisitely hand-drawn at a time when Hollywood animation was splurging on CGI, Spirited Away is a warm, rich vinyl record in a world of soulless, compressed mp3s.

Defeating bad guys through violence and superior masculinity is not a theme for which Hayao Miyazaki greatly cares, because life isn’t like that. His protagonists – usually young girls – overcome the odds through strength of spirit and emotional intelligence, and Spirited Away is no exception. And sure, there’s love between Chihiro and Haku, but their relationship is a mutually beneficial one; they both come to each other’s rescue at different points in the film.

Spirited Away

© 2001 Nibariki – GNDDTM

Crucially, all these themes are merely those apparent to a western audience. There’s an entire world of symbolism and metaphor that speaks to Japanese culture, and the sense that there’s so much more going on under the surface of Spirited Away is one of the things that keeps us coming back to it.

The nuance and indefinable nature of many of the ideas on display here are partly culturally specific, but at the same time they can be applied to the strongest of the film’s primary themes: the introduction to an intriguing and confusing adult world in which we struggle to assign meaning to that which we do not fully understand. As such, Spirited Away is far more than just a children’s film; it’s a look at ourselves, at where we’re going and what we’re doing. It doesn’t claim to have all the answers, but asking the questions has rarely been more enjoyable.

Spirited Away is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.