The Sound of Studio Ghibli: Joe Hisaishi and Princess Mononoke

David Farnor | On 01, Mar 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2015.

When you think of Studio Ghibli, you immediately picture Hayao Miyazaki’s beautiful hand-drawn animation, you think of the fantastical stories, you giggle at the gentle humour and celebrate the preponderance of female protagonists. But tying that all together is another, equally mesmerising force: Joe Hisaishi.

More magician than musician, the composer (whose real name is Mamoru Fujisawa) has worked on almost all of the studio’s films – and 10 out of 11 of Hayao’s. Just like his frequent collaborator, Hisaishi’s work is instantly recognisable and often unforgettable. He is responsible for nothing less than the sound of Studio Ghibli.

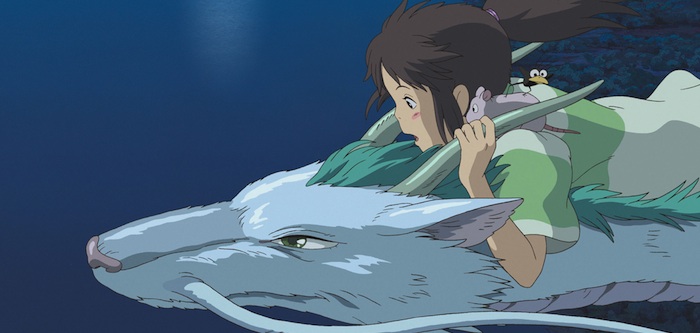

And what a sound it is. Play a few bars from Spirited Away to a fan and they’ll identify it as easily as they would a Totoro. There’s no doubt that the 2001 masterpiece is arguably the definitive Ghibli soundtrack.

The movie’s main theme establishes Joe’s favourite motif: a chord sequence that slides from the relative minor key through the fifth and fourth to arrive at the certainty of the first, only to slip back through the minor second and fourth to the cliffhanging fifth again (you can read more in detail about that in this very good thesis). It’s a journey that takes your ears from sadness to happiness to uncertainty in a few bars; from melancholy all the way to the charm of open-ended possibility.

Naturally, it’s played on the piano, Hisaishi’s instrument of choice – a listen to his fantastic concert in Budokan to celebrate the studio’s 25th anniversary shows the maestro in effortless ivory-tinkling mode. His comfort at the keys comes across in his deceptively simple melodies, almost always repeating a refrain while moving up or down a step, as the chords shift underneath. Then, he rolls a seventh up the piano; an arpeggiated sting you’d expect to hear in a jazz number, turned into the gentle tinkling of enchantment. You can almost picture a video game character discovering a hidden, magical object.

Spirited Away

© 2001 Nibariki – GNDDTM

But Joe’s not afraid to think big: Spirited Away erupts outwards into brass fanfares to announce its adventure, throwing in chopsticks and rapid quavers to convey chaos and excitement. It’s that contrast, even more than the chords, that defines Hisaishi’s style. Like Howard Shore’s The Lord of the Rings, Joe’s work manages to find enough space for gigantic scale yet still make enough time for intimate feelings. That balance between piano and orchestra, between tiny heroine and epic world, is central to the studio’s success: a blend of big and small that matches Miyazaki’s storytelling magic with Hisaishi’s own.

It’s recognisable throughout Ghibli’s work, in the cute pizzicato strings that give Kiki’s Delivery Service its cute humour to the uneven intervals the main theme jumps through to show her gradual mastery of flight; in the looped woodwinds and flurrying flute trills of Nausicaa opposite the drums and stabbing brass; even in Howl’s Moving Castle, despite its rare shift away from straight 4/4 time signatures into a lyrical, infectious waltz.

Hisaishi doesn’t just rely on the same old tricks, though. He’s also a firm believer in silence, never over-composing anything.

“According to Disney’s staff, foreigners (non-Japanese) feel uncomfortable if there is no music for more than 3 minutes,” he told Keyboard Magazine when commissioned to re-score Laputa: The Castle in the Sky’s re-release in 1999.

“You see this in the Western movies, which have music throughout. Especially, it is the natural state for a (non-Japanese) animated film to have music all the time. However in the original Laputa, there is only one-hour worth of music in the 2 hour 4 minute movie. There are parts that do not have any music for 7 to 8 minutes. So, we decided to redo the music as (the existing soundtrack) will not be suitable for (the markets) outside of Japan.”

Comparing the original 1986 score with the re-written one 13 years later shows you how much Hisaishi has grown alongside Studio Ghibli: from his early days, where he was a fan of electronic music, the 90s saw his love of full orchestras develop. What’s clear, most of all, is that whether it’s synth or symph, this is a guy who can orchestra the heck out of anything.

Just have a listen to Porco Rosso’s toe-tapping accompaniment, which uses trombones and a shimmering sax to capture the European jazz style of days gone by. (Bonus trivia: the pseudonym “Joe Hisaishi” – or “Hisaishi Joe” – is effectively a Japanese translation of Quincy Jones.)

Or, better still, Ponyo’s glorious soundtrack, which uses a lot of vocals (perhaps to conjure up a lullaby feel of a child’s bedtime story), but also features a rousing riff on Ride of the Valkyries that rivals Geoff Zanelli’s take on the William Tell Overture in The Lone Ranger for best musical arrangement in modern cinema. Timpani, eat your heart out.

In the face of all that, Princess Mononoke sticks out like a sore thumb. A sore thumb that happens to be very good at music. Why? Because it features almost none of the above.

Just as he was tinkering with Laputa, Miyazaki’s story of forest spirits and conflict landed in Joe’s lap – a story that is perhaps (discounting the mature biopic The Wind Rises) Hayao’s most grown-up of all. The result is an equally adult score.

Hisaishi’s ear for epic, orchestral music usually charms because it treats a child’s perspective seriously; like Totoro’s upbeat military march as Mei marches across a field, even the tiniest steps can seem like sprawling leaps across the globe. In Mononoke, though, the action is bloody, grimy and frequently lethal.

The orchestra doesn’t just arrive here: it announces its presence with a rumbling darkness. Cellos slowly move up minor thirds before The Legend of Ashitaka introduces its melody. But this no gentle keyboard ditty: this is a rousing line that, when it isn’t using that same melancholic interval, moves in full tones to give it the sound of a traditional Japanese legend. Gone are those familiar chord progressions: the orchestra is full of suspensions, ones that almost always resolve in sad chords, a mood emphasised by the pained pang of the oboe.

And that’s just the start of it. Battle Drums and the various Demon-themed tracks deliver Hisaishi’s best action licks to date, as wood blocks and Taiko drums tap out complex, contrapuntal rhythms; a dotted metronome that is soon overlaid with tangs, clangs, clashes and crashes that remain strictly in time but always feel like they could escape off the leash at any moment. Every now and then, strings rush up and down arpeggios, swirling without rest, driven by that non-stop momentum. Or a synth snakes down into ominous bass notes below.

Add in unusually chromatic brass and you have something quite alien to the world of Spirited Away and even the grander likes of Nausicaa or the Wagnerian Ponyo. By the time The Furies erupts, all offbeat squelches and trumpeting flutes, Joe Hisaishi reveals just how versatile he can be. Bad-ass and thrilling, Princess Mononoke is like his Star Wars – and he’s Japan’s John Williams.

But, like Williams, Joe still knows when to dial down the tempo.

Journey to the West takes Ashitaka’s theme and gives it a stately, mythical quality thanks to the nostalgic use of flutes, but it’s Ashitaka and San that really gets to the heart of Princess Mononoke: the melody reveals itself as three-step minor chord sequence that is echoed one third higher; a gentle act of support between the characters. Hisaishi plays this union out on piano, reaching up for the high notes with a lyrical, almost soppy, stretch. After the harsh sounds of earlier, it’s a treat to be back in the swooning arms of Miyazaki’s gentler fare. The fact that it occurs at the film’s climax is equally telling, as both Hisaishi and Hayao withhold the music you’d expect to hear, until they want to land their strongest emotional punch. (The film, in fact, is just as striking for its use of silence, with some battles taking place against just the swishing noises of swords and arrows.)

Perhaps more than any other, Princess Mononoke reveals the men as two storytellers who truly understand how each other’s work works; just as we recognise the trademarks of the director’s visuals, Miyazaki knows the sound of Hisaishi’s pizzicato harps, the upbeat vocals, the simple piano. And as that chord progression appears in Ashitaka and San – only briefly – and an arpeggiated chord rolls up the piano, you smile. Because you’ve just heard the sound of Studio Ghibli.

Princess Mononoke is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.