The Disaster Artist: Hayao Miyazaki and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Chris Blohm | On 01, Mar 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we delve into our archives to look back at what makes them so magical. This article was originally published in 2015.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is the second film from legendary Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki, based on his own manga series. Although the movie pre-dates Ghibli, Nausicaä’s success laid the foundations for the animation studio. For that reason above all others, it’s kind of a big deal. Influential, too: Miyazaki’s ideas and imagery continue to reverberate in science-fiction staples as diverse as Beasts of the Southern Wild and Avatar.

The film arrived in 1984, at the tail-end of the Cold War and during the emergence of the sustainability movement. A rather earnest, unapologetically Buddhist picture, Nausicaä can be viewed both as a reflection of the environmental concerns of the time and as an astonishingly prescient glimpse into darkness. This early version of Miyazaki doesn’t come across as a wide-eyed, castle-building visionary of future islands and fantastic voyages. At the beginning of Nausicaä, he’s practically a harbinger of doom, albeit with an intriguing morality tale to tell, and lessons to teach in the event that humanity dares repeat the mistakes of history.

And what mistakes they turned out to be. Chillingly, the numerous ‘scorched earth’ premonitions of Nausicaä started coming true within a couple of years of the film’s release. In 1986, an explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine discharged a devastating quantity of radioactive particles into the atmosphere, putting hundreds of thousands of lives at risk, and sealing off a good chunk of the Soviet map in the process.

More recently, in 2011, Japan suffered its own atomic emergency in the form of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, when three of the plant’s six nuclear reactors went into meltdown as a direct result of the Tōhoku earthquake and the accompanying tsunami. This was a significant and shocking milestone. Two hundred thousand people were evacuated from their homes, and the incident triggered a complete overhaul of the country’s regulatory approach to nuclear power.

Japan’s complex relationship with atomic energy has been well documented on the big screen. When former prisoner of war Ishirō Honda made Godzilla, he didn’t need to try particularly hard to conjure up images depicting the incineration of the modern world; his country had already experienced it first-hand, thanks to the war-time atrocities committed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not to mention the unfortunate events surrounding the Daigo Fukuryū Maru. (The Daigo Fukuryū Maru, or Lucky Dragon No. 5, was a Japanese fishing vessel that sailed straight into the fallout zone of the nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll early in 1954. Amazingly, many of the crew survived – some of them into old age – but not before suffering severe sickness due to radiation exposure.)

© 1984 Nibariki – GH

Honda exposed these fears and laid them bare: Godzilla’s iconic assault on Tokyo is nothing, if not the most ghastly and ominous extinction prophecy in the history of science-fiction cinema. As J. Robert Oppenheimer famously said, in the words of the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The allegorical roars of Honda’s hallowed kaiju fable may well have been ringing in Miyazaki’s ears when the Ghibli maestro wrote the sinister prologue that frames his own futuristic survival fantasy: “A thousand years after the collapse of industrial civilisation, the Sea of Decay, a swamp exuding toxic vapours, covered an Earth strewn with rusting ruins threatening human survival.” It almost reads like the beginning of some psychedelic Godzilla sequel, in which the monsters have taken over the world and made the entire place uninhabitable for Homo sapiens and other, similarly stunted, species. There are also echoes of another national ecological calamity, the pollution of Minamata Bay during the Sixties and Seventies.

But despite the grim set-up, Miyazaki offers glimmers of hope. In the next scene, following a credit sequence in which humanity’s downfall is artfully documented in portentous tapestries, we’re introduced to a girl in a gas mask, apparently playing with blithe abandon in the dreaded Sea of Decay itself. She is, to all intents and purposes, enjoying herself beyond all reasonable expectation.

Miyazaki starts subverting his premise almost immediately.

Firstly, the ‘Sea’ of Decay isn’t really a sea at all; it’s a vast, ecologically complex jungle, blighted by the spores and smog of an ancient catastrophe and mortally noxious to humankind. Life does thrive here, just not the kind you would expect. Giant bugs rule the land and skies. Think Avatar’s Pandora meets the Genesis planet from Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, with a solid dose of William Burroughs and Frank Herbert thrown in for good measure.

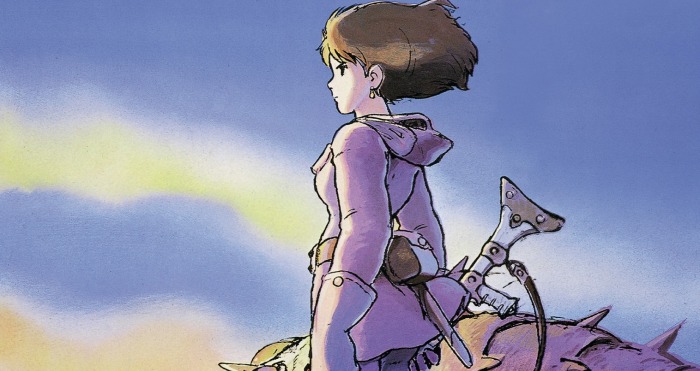

Secondly, this is no ordinary girl. This is Nausicaä: princess, warrior, explorer. Above all else, she is a scientist. As the scene progresses, it becomes clear that Nausicaä’s not playing around at all. She’s studiously and compassionately observing her accursed world, together with the monsters that lurk within, forever hopeful of finding a cure for the plague that threatens human extinction.

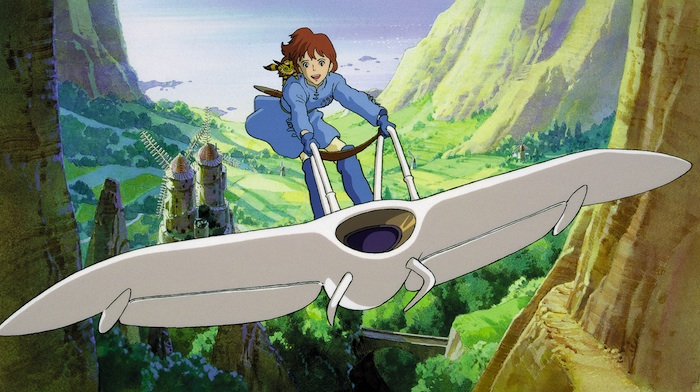

© 1984 Nibariki – GH

Nausicaä lives in a rural settlement called the Valley of the Wind. Her family and friends are simple, spiritual folk, who live in fear of the growing toxic threat from the Sea of Decay. One day, they’re invaded by Princess Kushana and the soldiers of Tolmekia, a more industrially advanced tribe that travels the planet in enormous, steampunk-style bombers of the kind Miyazaki would ultimately obsess over and fetishise in his 2014 film The Wind Rises. By way of comparison, Nausicaä herself flies a simple but versatile glider, free from mechanical dependence, and reliant solely on what nature provides. (Incidentally, there’s a very cool shot towards the start of the movie in which Nausicaä jumps onto her glider and shoots off into the barren, sandy distance. It’s eerily reminiscent of the moment Daisy Ridley grabs hold of her speeder in the Star Wars: The Force Awakens trailer – perhaps JJ Abrams is a Miyazaki fan?)

Kushana brings with her the ‘Giant Warrior’: a living, breathing biological weapon that looks like a cross between Alan Moore’s diabolical squid demon from Watchmen and a genetically modified walrus. Her intention? Use the Giant Warrior to destroy the Sea of Decay, and wipe out the huge, psychic, trilobite creatures known as Ohmu along the way. Kushana is a blunt but necessary metaphor: a bitter, technological despot, driven by ideology, and hellbent on deploying the cause of mankind’s own downfall against a false enemy. The destructive, immoral antithesis of Nausicaä’s voice of peace and reason, in other words.

In this battle for the future of the human race, it’s easy to see where Miyazaki’s sympathies lie. As the film swoops exhilaratingly towards its surreal, tentacular finale, Nausicaä emerges as the hero the world needs, though not the one it deserves. When faced with the ultimate destruction of everything we hold precious and dear, perhaps only the curiosity, audacity and bravery of youth can save us after all.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

This article was originally published in 2015. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.