VOD film review: Dunkirk

Review Overview

Direction

10Action

10Cast

10Rating

David Farnor | On 28, Dec 2017

Director: Christopher Nolan

Cast: Mark Rylance, Tom Hardy, Fionn Whitehead, Barry Keoghan, Harry Styles

Certificate: 12

“All we did is survive.” “That’s enough.” That’s the heart of Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, and the fact that it can be read in two ways is what makes this war movie such a powerful watch. There’s a rousing, patriotic message to be found in the stirring tale of how the UK deployed tiny, civilian boats to bring back thousands of men from the shores of France. Why? Because the larger boats couldn’t get to the beaches, and repeatedly drew fire from enemy bombers. If that sounds like a smart tactic, Dunkirk strips away national pride from the situation: this wasn’t a military strategy; it was a desperate last resort.

Christopher Nolan has always been a storyteller with a knack for stripping things down: compared to the bombast and sentiment of Spielberg, he’s a clinical, detached master of clockwork. If Saving Private Ryan is a moving, stirring war film with gripping action sequences, Dunkirk is a raw, visceral war film that cuts out everything but the terror and tension of conflict: the overriding sentiment here is fear.

Nolan expertly escalates it threefold, by charting the countdown to the evacuation from three perspectives: the soldiers on the beach of Dunkirk, one week before the rescue; some civilians on a boat, on the day of the rescue; and a fighter in the sky, one hour before the rescue. It sounds convoluted, but it’s a puzzle box perfectly designed for this last-ditch solution, multiplying the immediacy and intensity of the challenge.

The soldiers (led by an excellent, resilient Ffion Whitehead) find themselves repeatedly trying different methods of escape. A moving, wordless turn by the ever-expressive Aneurin Barnard captures the horror of staying just through his widening eyes of realisation, while Harry Styles’ aggressive trooper conveys the gruff determination needed to leave that beach. Nolan trusts their performances to portray the hell of this existence, and the length of time we spend with them only reinforces the impossibility of surviving – there’s a doomed inevitably to how their every effort seems cursed to fail.

The civilians are headed up by Mark Rylance’s Dawson, a stiff-upped-lipped father who brings his sons (notably the sadly naive Barry Keoghan, worlds away from his turn in The Killing of a Sacred Deer) with him on their valiant quest – and it’s their tiny decisions, what truths to tell the troops they pick up (watch out for a shell-shocked Cillian Murphy), and their growing understanding of the task they’re undertaking, that brings soul to these events. Nolan is a director who doesn’t always successfully invest his movies with feelings, but his tri-part structure gives us the chance to become engaged in their smaller stakes, in a way that wouldn’t happen with a straightforward linear narrative.

Above them all flies one heroic pilot, Farrier, played with aplomb by Tom Hardy, who is surely the best Brit working today when it comes to acting with a mask over one’s face. Manually tracking his dwindling fuel supply, Farrier’s charismatic and calm to the last – and as the film jumps back and forward in time, we can see the impact his every shot has upon the lives below.

Seeing each tumbling vessel, flooding chamber and exploding bomb in triplicate becomes an almost hypnotic experience, as Hans Zimmer’s pounding score unites every plot strand with the same, ominous ticking of time – the seconds until hope finally arrives, or until death inevitably strikes. All the while, the booming, deafening notes and screeching, sliding strings combine seamlessly into the background noise of slaughter; a cacophony of despair that’s anchored by the stillness of Kenneth Branagh’s Commander, who stares into the distance from the pier at the British shores on the horizon. (Nobody stares into the distance quite like Kenneth Branagh.)

By the time the strands collide, and Farrier swings into place over Dawson’s craft, there’s a thrilling sense of a plan coming together – a brief glimpse of hope. But Nolan’s vision is bleaker than that, as his precision-tooled machine drives up the trauma to the very final frame – and that ticking soundtrack tells of the fact that the end credits are just a pause until the next battle starts up, engulfing the survivors once more.

The result is a filmmaker working at the top of his game. If Inception saw Nolan toy with the form of mainstream blockbusters by ambitiously playing with chronology and structure, this is the elegant, harrowing masterpiece it led to, as those same techniques are used in service of a greater story. The word Dunkirk is often associated with Churchill’s iconic address, a defiant speech of resistance and strength. Nolan’s Dunkirk tears that down and builds on these helmet-strewn beaches a story of pride and defeat; a victory that cannot overcome the casualties that went before and after, and a newspaper headline that can be read both ways. Surviving was enough for us to win the war, but this is one battle everyone lost.

Related Posts

Barry: Full trailer lands for Netflix’s Obama drama... November 23, 2016 | David Farnor

Christopher Nolan wrote to Netflix to apologise for “mindless” criti... November 8, 2017 | David Farnor

Netflix UK film review: Barry December 20, 2016 | Josh Slater-Williams

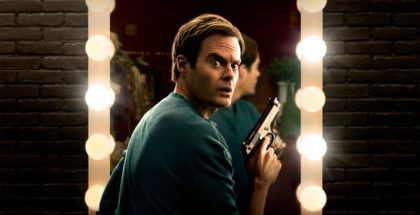

Why you should be watching HBO’s Barry June 16, 2019 | Chris Bryant