True Crime Tuesdays: Outcry

Review Overview

Ease of viewing

6.5Balance

6Puncturing of assumptions

8Helen Archer | On 08, Sep 2020

On Tuesdays, our resident true crime obsessive gets their fix with a documentary film or series. We call it True Crime Tuesdays.

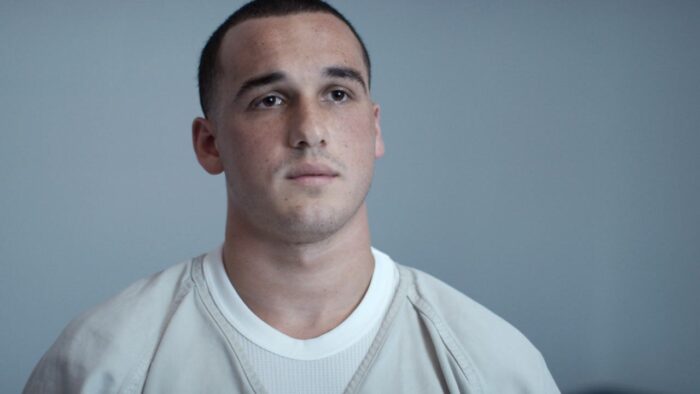

This five-part documentary charts the story of Greg Kelley, a talented high-school football player with a promising future who saw his life turned upside down in 2013, after being accused of sexually accusing a 4-year-old boy. Director Pat Kondelis spent three years filming his struggle to clear his name.

In recent times, much criticism has been given to foregrounding an accused sex offender’s aptitude for sport as a mitigating factor for their alleged crimes. Brock Turner, the “Stanford Swimmer” convicted of sexual assault in 2016, is perhaps the most infamous case, although there is a long history of men being partially absolved for their wrongdoings through their prowess on the athletic arena or in the classroom. Nowadays, we’re almost hard-wired to push back against any such attempt at exculpation. Yet this is a series which seems, in the first couple of episodes, intent on wrongfooting not only the viewer, but some of the participants.

Kelley’s emerging sporting career is highlighted from the beginning, as the film details his background in Williamson County, Texas. Although, on the face of it, Kelley seemed to have it all – talent, popularity, a devoted girlfriend, and the prospect of a full college scholarship – the 17-year-old had, in fact, been through considerable stress for his young age. His parents were struggling with serious health issues and Kelley was sent to live with the family of his friend Jonathan McCarty, so that he could concentrate on school. But this is where his problems really began.

McCarty’s mother ran a daycare service from the house in which Kelley was staying, and in 2013 one child who spent his time there made an outcry – the legal term for the first allegation made by a victim of sexual abuse. That child told his parents, and later the authorities, that Greg Kelley was the perpetrator.

Initially, the viewer – like the public, the police and the victim’s advocates – are primed to believe the accusations. And, while the detail is murky, it’s clear that something terrible happened. By withholding certain information until later in the series, the programme almost challenges us to go against our instincts. It makes for uneasy viewing.

By the time Kelley was found guilty and sentenced to 25 years in prison without parole, he had amassed a number of supporters. Protests sprang up outside the courtroom, and vocal spokespeople, led by Jake Brydon – a stranger to Kelley who nonetheless believed wholeheartedly in his innocence from an early stage – took up his cause. Yet even the protesters seem unable to articulate just what it is that makes them so sure of Kelley’s righteousness. Without any other explanation, there seems to be, in some cases, a blind belief that such a clean-cut athlete couldn’t be capable of such a crime.

It’s only about halfway through that the programme starts showing its hand, by investigating the way in which the initial police case was mishandled, and the poor practice of the child trauma interviews, before revealing that there is good reason to suspect that another person – Kelley’s “best friend”, McCarty, who looked startlingly like Kelley – was behind the abuse. At which point, this becomes a labyrinthine tale of police failure and prosecutorial misconduct, and hints at some larger conspiracy, as the lawyers fight it out in court and Kelley finds his life on hold.

For such an emotionally-charged subject matter, the whole series is curiously unaffecting. For fairly obvious reasons, we have no access to the victim or the victim’s parents, meaning we don’t get to hear their side of the ordeal. The result is somewhat unbalanced. Kelley himself is something of a blank slate, even as he explains the toll the accusations have taken on him. The unwavering support of his family, his girlfriend, and his network of supporters – most of whom never once seemed to question his innocence – must have been some solace. Without them, his hope and will to fight would doubtless be less strong. Without them, he may yet be serving his original 25-year sentence.

While initially questioning the belief of certain of his advocates, this ultimately turns into a programme about the failures of police and prosecutors – just not, perhaps, one that follows the same lines viewers are used to. Kelley doesn’t fit so easily into the category of those who fall through the cracks of the justice system, be it through race or class or gender. He received the support not because he was atypical of the crime, but because he was atypical of a miscarriage of justice. Perhaps that is what shocked so many people, and thrust them into action – wrongful conviction is something that could, as is stated throughout the series, happen to anyone.

Outcry is available on Sky Crime. Don’t have Sky? You can also stream it live and on-demand legally on NOW, for £9.99 a month, with no contract and a 7-day free trial. For the latest Sky TV packages and prices, click the button below.