Netflix UK TV review: Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes

Review Overview

Archive materials

10Narrative

8Themes

10Martyn Conterio | On 03, Feb 2019

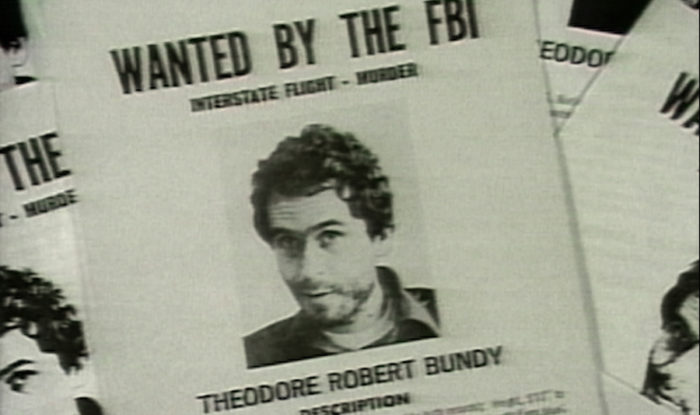

In 1989, Ted Bundy, a serial killer responsible for the deaths of at least 36 young women and children, was strapped to Old Sparky in a Florida prison and executed. Upon arrest in 1975, his string of “extremely wicked, shockingly evil and vile” crimes (to quote Judge Cowart) caused a media sensation. Around this time, the FBI Behavioural Science Unit had coined the term ‘serial killer’ to categorise a specific type of repeat offender. It boasted a catchiness that entered pop culture.

Subsequently, novels and movies further cemented their position and sensationalised these men (and, on rare occasion, women), turning them into super-criminals. Joe Berlinger’s documentary works as both an exploration of a mind insane and how society and culture reacted to men like Bundy. It didn’t seem to matter that many killers were in fact below-average intelligence or just about average. Yet the manner of their outrageous provocations, overpowering compulsion to harm others, and ‘catch me if you can’ brazenness was less from an inherent Professor Moriarty-style genius and more to do with police bungling, lack of urgency and imagination in seeing pattern homicides, and law enforcement agencies refusing to cooperate. But we tend not to see things that way. Strings of dead bodies, grieving families, mystified cops, valiant journos hitting the beat for fresh information… it all begins to feel like a thriller, with documentaries and movies tending towards this format.

The antithesis of an ogre-like fiend, Bundy didn’t outwardly look like a wrong ’un. Ted Bundy was the boy next door. He was good-looking and educated. He knew how to act normal. How to ingratiate himself to people. He could be charismatic and funny. These traits were not genuine. They were superficial, empty, a mimicking of human behaviour. But it did the trick – devastatingly so. Bundy himself said in very rare moments of honesty and candour that he didn’t know how to connect with people or understand everyday interactions freed from his obsessive, controlling thoughts. And people were tricked. Family, friends and acquaintances would find it absurd, when he cropped up as a suspect. The notion ‘Ted wouldn’t harm a fly’ is precisely why he was able to do what he did. It wasn’t because folk were stupid. The victims were certainly not stupid. His persuasive shtick was matched to a chameleon-like ability to change appearance. He didn’t need false noses, glasses and wigs to alter the way he looked. Multiple photographs – taken while at liberty and in jail – highlight how weight loss, hairstyle, clothing, camera angle and lighting did the job. Some eyewitnesses saw right through it, others were unsure. Bundy was very aware of this unusual trait in his physiognomy, too.

Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes sets its stall as a disturbing but rewarding journey into the heart of human darkness. It should be applauded for seeking to enlighten and for pulling back the curtain. Bundy was not a mastermind crook, even when acting daringly (such as his escape from jail on two separate occasions). As we learn, he was a narcissistic psychopath who fed off media notoriety.

What Berlinger does is use 100 hours of audio tapes and extraordinary archive footage to put together what is tantamount to a deprogramming session delivered in four parts. Not to ween us off our societal addiction to true crime, because that would be utterly impossible and do little good to the general quest for knowledge in human psychology, but to at least move beyond the entrenched exploitative elements and tactics of television and relish the opportunity to strip away decades of untruth. It does so without being nagging, po-faced or piously moralistic. It tells us straight: Bundy’s image was a fraud, the mythology BS.

Bundy never confessed wholly to his crimes. Instead, he issued blanket denials, offered piecemeal info, often referred to incidents obliquely or talked about the case as if he was a profiler discussing the actions of another person. That was how journalists Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth were able to coax him into revealing discussions on cassette tape – by having Bundy talk in the third-person. He famously dubbed his misanthropic actions as ‘The Entity’, as if he wasn’t in control during the murders. Another in a long line of Bundy cop-outs. Ted Bundy wanted power and dominion over others. With young women, it meant their demise and warped post-mortem activity. With police detectives, journalists and the public, it meant game-playing with information. In his very last interview, conducted with a religious leader, a day or two before he rode the lightning, Bundy glibly informed the world about the dangers of pornography and its capacity to turn young men into maniacs. He could never admit – on record – that he did the things he did because then people would lose interest and he’d lose his powers.

It’s all self-deception twinned with what appear to be self-destructive tendencies (medical professionals differ in diagnoses to this very day). Plenty of times, he could easily have been acquitted – as there was very little evidence in a lot of the individual cases – only for Bundy to screw himself over. He projected rationality while simultaneously acting deeply irrational. The narcissism is staggering, and it’s something Berlinger zeroes in on. Far from the smartest guy in the room, Bundy’s repeatedly poor judgement is astonishing.

The co-director of the acclaimed Paradise Lost trilogy, Berlinger sparingly uses graphic crime scene photography; Bundy’s infamous modus operandi is barely touched upon (arguably because it’s so well known) and lurid details of what Bundy did to young girls tends to be vague or used for well-timed shock effect (particularly in the latter stages of the fourth episode).

By the end, Bundy’s ceaseless parade of lies, half-truths, sneakiness, bland insights into his life and excuses for extreme behaviour becomes exhausting, the absence of emotion repulsive and horrifying. It’s easy to agree with the Florida detective interviewed, who refers to Bundy as “garbage in human form”. But what is so disquieting, eerie, thought-provoking and nightmarish are the questions Berlinger’s must-see doc raises, yet cannot hope to answer. “Why are there people like Ted Bundy?” is the big one.

Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes is a major achievement because Berlinger constructed his epic four-hours-plus doc as a complete demystification of a big bad wolf. It gives us what we need, not what we want.

Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.