National Theatre at Home review: A Streetcar Named Desire

Review Overview

Cast

10Staging

10David Farnor | On 21, May 2020

Read our interview with director Benedict Andrews

“What is straight?” asks Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire. “A line can be straight, or a street, but the human heart, oh, no. It’s curved like a road through mountains.”

That’s what the Young Vic’s production of Tennessee Williams’ 1947 play manages to capture on stage: the curve of the human heart and mind. When the traumatised Blanche arrives on the doorstep of sister Stella’s apartment in New Orleans, she is hoping for a straightforward stay. In no time, she locates the liquor under the sink and takes a swig. The room immediately starts to spin. It doesn’t stop.

It’s a stunningly bold piece of design from Magda Willi: staged in the round, the production centres on Stella and Stanley’s home, an exposed unit on a turntable that constantly, slowly revolves.

On a technical level, it’s an impressive feat: under the careful eye of director Benedict Andrews, things are choreographed seamlessly so that people hop on and off the carousel of Blanche’s downward spiral, hanging off stairwells or slipping out into the wings just as the opportunity arises.

On a practical level, it’s also what makes this version of A Streetcar Named Desire perfect for an NT Live recording. While sitting in the theatre, every scene rotates to be shown from always-shifting vantage points – a process that might sound distracting but is anything but. In fact, it’s actually very cinematic, like watching a screen that repeatedly pans to another character’s perspective; a restless, uneasy experience that taps directly into Blanche’s crumbling mental state.

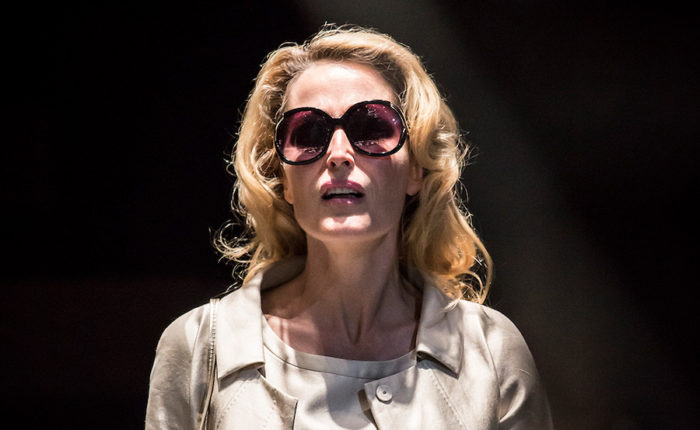

Gillian Anderson is jaw-dropping as the faded belle, simultaneously attractive and pathetic, powerful and pitiful. “I don’t tell the truth, I tell what ought to be the truth,” she insists to her sister (the equally wonderful Vanessa Kirby), impressively stubborn in her deceit, but tragic in how she has fooled herself. Ben Foster echoes her subtle turn with a similarly nuanced Stanley, giving the plain-speaking brute a soft, sympathetic edge. When he throws plates against the wall, he doesn’t yell like an ape; he almost resentfully tips them with a casual flick, more conflicted than crude.

As this trio collide in varying combinations, a normal in-the-round production would see you miss parts of their performances. Andrew’s staging, though, amplifies every detail. Sitting behind the sink adds to the home’s claustrophobic confines; swooping behind the door during a row leaves you eavesdropping from the bathroom. It’s a perfect display of how to make obstacles and props a part of the text, turning background into foreground.

Throughout, Alex Baranowski’s music creates an oppressive atmosphere that adds to the voyeuristic feel, while rough and ready song choices during scene changes echo the action with the irony you’d normally associate with the end credits of Mad Men.

When Blanche dresses up for a birthday party halfway through, flashing lights and colourful decorations create the illusion of spinning top, a circus act gone horrifyingly wrong. The spinning production’s most powerful aspect, though, comes in between the lines. When Blanche insults Stanley to Stella, he stands behind the mesh front door, hearing everything; like the audience watching this abstract unit of architecture, he sees no wall there. When Stanley later talks to Stella about Blanche, she sits in the bath, isolated by a shower curtain singing show tunes – an element that would normally take place off-stage. We still move through the home without boundaries, but for Blanche, those walls actually exist; she is the only one who hears nothing outside of her own world. Overhearing from behind the kitchen sink, the division between reality and fantasy has never seemed more visible.

The result is a rare example of a production that could be recorded just by leaving a camera in one static position, as Blanche’s descent into madness repeatedly cycles into view. The screen may be straight, but Benedict Andrew’s A Streetcar Named Desire is dizzyingly curved.

A Streetcar Named Desire is available on YouTube from 7pm on Thursday 21st May until 7pm on Thursday 28th May.

For more information on National Theatre at Home, including other plays being released online for free, click here.