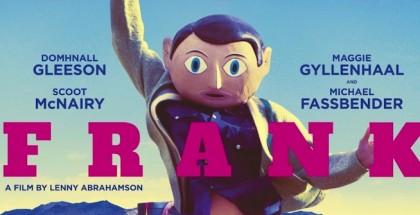

Interview: Lenny Abrahamson (Frank)

David Farnor | On 15, Sep 2014

How do you know if you’re any good at something? Who hasn’t asked themselves that? For those in creative industries, where their careers depend on the subjective opinion of others, it’s an even more pressing question. Frank, out now on VOD, DVD and Blu-ray, attempts to answer it – using theremins, Michael Fassbender and a giant papier mache head.

We chat to director Lenny Abrahamson about his oddball comedy, making music and the finding the balance between art and success.

Frank follows Jon, a keyboardist (Domnhall Gleeson), who winds up in a weird band called Soronprfbs, led by the charismatic Frank Sidebottom (Michael Fassbender). Frank is impulsive, confident, talented and wears a giant papier mache head. He’s everything that Jon is not – particularly the giant papier mache head. And so we see Jon try to find his role in the group.

It’s a situation that Lenny identifies with. Rewind 28 years to when he was 20 years old. Was he in a band?

“Yes!” he tells us. “I was in several really, very, almost profoundly forgettable bands.”

Most were with friends, he explains, and were “never serious”, just performing gigs in pubs around Dublin. He played, he wanted to play, but, he smiles, they were “never good enough”.

The parallels with Jon jump out immediately – although Lenny wasn’t a keyboard player. He played guitar.

“That and standing around looking a bit awkward,” he laughs. “That was my main function in the band. You know when you think you’re supposed to be there, but deep down you don’t really believe you should be there, you know? That sort of look?”

Fast forward 28 years and the director admits that the feeling stays with him – as they do with any person in his line of work.

“Those questions about whether you really are able to do what you want to do, whether you’re deluding yourself or whether it’s real, I think they attach themselves to any creative endeavour, you know?” he muses.

Indeed, Frank’s triumph is that it doesn’t buy into the expected formula of artistic success that we’re sold in the media. It is, on one level, a satire against the Britain’s Got Talent machine.

“That’s exactly what it is,” agrees Lenny, warming to the point. “It’s the opposite of The X Factor, of someone standing there saying ‘I can be famous, I will be famous, just through sheer effort.'” That reality TV show narrative – which Lenny terms “a whole lot of cliched nonsense about wanting it enough” – has no place in Frank Sidebottom’s world of strangers and self-doubt.

This subversive nature gives the move an unpredictable edge, which is part of what the director liked about the project.

“Because the film itself is a celebration of work outside the mainstream, its own structure tries to be fresh and avoid those cliches. For an audience not to know what’s going to happen next, but for it to make sense when it does happen…”

The approach goes right down to the casting of Michael Fassbender in the lead role – someone whose face we never really see.

“The fun of doing that, of taking something a face so well-known, that people are so keen to photograph, and hide it felt like the right thing for the film.

“It’s about how people present themselves and inflate themselves and how myths are created – and a famous actor, they are part person and part brand. So to take that part away and be left with the actor was something that seemed to make a lot of sense.”

Fassbender himself seems to revel in the limits of the giant head mask.

“You marvel at how good he is, in a way!” enthuses Lenny. “I don’t know why it’s more strongly felt when he’s masked than when he’s fully visible. It does give you an encounter with Fassbender that’s very pure.”

While in the film, Frank has to say his facial expressions out loud for Jon to understand – welcoming smile – did they resort to any of that on set?

Lenny says that it was a worry at first.

“But I don’t know, partially because the head is a canvas upon which you can project, we all on set just accepted that was the character. It was a very natural way of working. We never had to adjust what we were doing. He was just that person. And the scenes are written in a way that acknowledged that. It was quite seamless in the end.”

They ended up using five or six different heads during production, including one “hero head”, he says – “if you can describe a bug-eyed, harmlessly smiling head as a ‘hero’!”

Fassbender wore that head most of the time, the director explains, although they had spares for scenes where he’s on stage or gets damaged. On one, they cut the eyes out so if he was running, he could actually see.

But Michael liked the constraints of the head physically too. “It affected the way he moved, so it always seemed to be a better take when he wore it.”

What Frank also achieves is to attract a cast full of starry names, despite telling a small, highly unusual story. Was it ever a problem getting those people on board?

“Donmhall came on board the earliest,” says Lenny, “he just really understood what I was trying to do.”

One of the talented Gleeson clan, Domnhall is credited with writing some of his character’s songs – such as “Lady in the red coat” – which form a central part of the movie’s themes and sound.

“He was fabulously giving in the department of writing terrible songs!” chuckles Lenny. “We hit it off extremely well from the beginning.”

Once Michael was shown the script – “and just really responded to it” – that was the step that helped secure Maggie Gyllenhaal as mildly psychotic theremin player Clara.

The actress, though, was reluctant at first, as artistic uncertainty looms its head once more.

“When I met Maggie, she did say – we had a great conversation – ‘Look, I just don’t know how this will be. It’s tonally so hard to imagine and I don’t know if I could do it.'”

“But she called me a few weeks later,” continues Lenny. “She couldn’t stop thinking about it and decided she wanted to do it. The script had that affect on people.”

Lenny confesses he had the same reaction, those questions lurking in his head as he signed on: “I had that experience myself. I thought ‘Am I really going to make a film about a man in a big head?’ There were so many ways it could be a catastrophe.”

How mindful was he of the film’s shifting tone – part funny, part serious, part sad – during the shoot?

“Very. There are some sharp corners the film takes and they have to be taken very carefully, otherwise you just go straight on and hit the wall. I had a territory the film was in and I was pretty sure I could move around that comfortably. That is that tradition of tender slapstick and sad slapstick and that’s an area I really understand. But Frank does go to dark places. Some of those were darker than I anticipated and it was really just a question of trusting that it would work. In the editing, there was more crafting and massaging of those transitions until it felt more truthful.”

That truthful element is arguable something that Lenny has often managed to bring to his work, even if this project does take him a long way, geographically, from his roots.

“I see some through lines, yeah, I do,” the director considers. “It’s a different kind of energy to the films I’ve already made, but there are deeper connections, I think, to meandering, slightly overwhelmed characters and slapstick elements and probably that kind of humane quality and that idea of tonal shifts, that’s in my other films a lot.”

The main aim, he says, was to save it from being a “kind of chirpy, quirky oddity”. A warning light for many was the film’s prominent use of social media – modern technology, if used inaccurately, can sink an entire production.

While Frank uses Twitter and YouTube with an amusing authenticity, Lenny reveals that they were not intended to be part of the story in the beginning.

“The script was originally set in the 80s,” he tells us, “and the story of Frank was recounted by this older Jon looking back. In that script, we used Jon’s voiceover.”

But Lenny wanted to introduce a simpler structure and make it “more contemporary and direct”. In the new script, though, there was no place for voiceover.

“There is something that voiceover helps, that process of compression,” he adds. “And I was travelling a bit with Jon and he’s big on Twitter and I had the idea of using that as a different sort of voiceover – a very self-promoting voice. And then that fit into the ideas of self-promotion, self-marketing, that DIY mantra. And it seemed to again just mesh very well with the deeper themes of the film.”

A tweeter himself, it’s not hard to imagine Lenny – like Jon (and Jon) – sitting at his phone composing mundanities to share with the world, while wondering whether his latest creation is up to scratch.

But unlike Soronprfbs, we’ll never have the chance to hear his own attempts at music (although Abrahamson is credited on the soundtrack alongside Gleeson and composer Stephen Rennicks). Where are all those tapes from 28 years ago?

“All of have receded into the – thankfully – pre-internet archaeological lair,” he laughs, “never to be paraded in front of me on a chat show!”

Any doubts about his artistic talent, you sense, deserve to be equally long forgotten.