Lost classics: Why the end of FilmStruck matters (and what to do about it)

David Farnor | On 11, Nov 2018

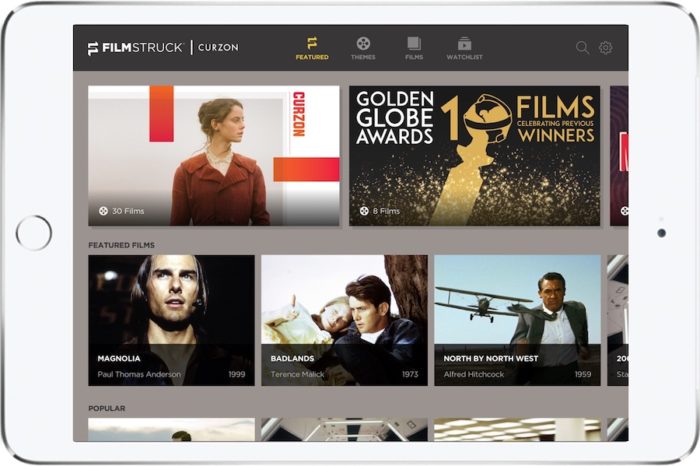

Thursday 29th November will see the end of FilmStruck as we know it. The joint venture between Turner International’s Digital Ventures & Innovation Group and Warner Bros. Digital Networks first opened its online doors in 2016, becoming a key platform for cinephiles, thanks to its focus on classic, arthouse and indie cinema – titles often overlooked by larger streaming players, such as Netflix. Earlier this year, FilmStruck teamed up with Curzon in the UK to launch on British soil, marking its first step into international territory. Less than a year later, though, the whole of FilmStruck is ceasing operations.

The decision, announced last month, is the kind that can be commonplace in this booming tech era, as AT&T (which recently acquired Warner) looks to cut down and consolidate its online presence. FilmStruck itself may have been successful as a specialised website, but as corporations merge to compete in a fast-moving, online environment, and big numbers are moved from one column to another, the idea of something niche doesn’t hold much commercial sway. Ironically enough, it’s a subject that’s tackled in a poignant segment (starring Liam Neeson) of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a Netflix original film that has sparked its own debate about the streaming company making more films available in cinemas.

It arrives at a time when John Lewis has announced that it will no longer sell standalone DVD players in its stores – once a fixture in every living room beneath every TV set. It feels like a turning point for the film industry and film community, the point at which we can decide what to do with cinema’s past and shape cinema’s future.

It’s not the fault of VOD that there’s a lack of support for classic films in a commercial marketplace. The clock has been ticking on the issue ever since the beginning of cinema: something like 90 per cent of all silent films and half of sound films made in America before 1950 have disappeared forever – even King Kong doesn’t have its original camera negative intact anymore. Preserving movie history is essential; losing stories, voices and experiences can only be damaging to our culture and our civilisation, preventing us learning, engaging and empathising with others, both from our past and present.

Indeed, online video presents a remarkable opportunity to store, restore and retain films for generations to come. The BFI’s Britain on Film is just one initiative that’s making miraculous use of digital technology, with 1000s of archive films available for free on BFI Player, showing people areas of the UK they grew up in or their families went to school in, dating all the way back to 1902. Netflix, meanwhile, proved the kind of powerful clout streamers can have when it stumped up a whopping big cheque to finally free Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind from a sea of legal claims, so that it could be removed from a Parisian vault, restored and completed – you can now see it on any phone, tablet, TV or computer with Netflix in the world for less than a tenner a month.

The opportunity for access as well as preservation makes FilmStruck’s closure all the more poignant: the Internet is a great leveller, making movies available easily and affordably for people, regardless of their location and background. But it’s also a warning: that access can end unexpectedly. Black Mirror’s taught us repeatedly that the proverbial cloud can stretch out into a terrifyingly infinite void, but a company can still come along and turn off the rain whenever they choose – a thought almost as upsetting as that tragically poor extended metaphor.

A recent news story that fanned outrage online saw a man suddenly lose access to a heap of movies in his iTunes collection. That wasn’t because Apple deleted a ton of films, but because he changed regions, stopping himself from being able to access parts of his own library. But it’s still a cautionary reminder of how complex digital rights have become. As the industry still tries to adjust to the online age and all of its ramifications, the fact that things aren’t universally available at the same price and in the same version is both an important reality of a commercial marketplace that has historically drawn lines between territories and distributors, and a frustrating technicality. Permanence is, in an ideal world, theoretically possible, but there are endless pages of terms and conditions to scroll through first – and we may never reach the “Agree” button.

So, in the wake of FilmStruck’s closure, what can you do?

Firstly, be aware of what you’re getting when you watch a movie online. If you’re buying it, you’re purchasing the right to watch it through that particular provider, for as long as they have that movie available. Going with the largest possible provider, such as Apple or Amazon, is perhaps as close as you can come to having that film available to watch for the rest of your life – they’re more likely than smaller streaming players to stay in business, although they are also, like Warner, arguably more likely to wind up in some kind of merger with another entity that could have all manner of unforeseen consequences. Physical media, then, is the only way to guarantee a permanent copy of a film in your possession – as long as you’re not hoping to buy a DVD player from John lewis.

Awareness of what sites are available is also important. In the USA, FilmStruck was the go-to place for arthouse, independent and world cinema, not to mention the Criterion Collection. In the UK, however, we’re lucky to have a number of different streaming platforms that cater to the same need, such as MUBI and BFI Player+. Essentially rivals to FilmStruck, they could both be potential online homes to the Criterion Collection in the UK (the label previously had a deal with MUBI).

In short, don’t pin all your hopes on Netflix: it may be the streaming service that gets the most news headlines, but it’s not the only platform out there. If you are a committed Netflix user, though, don’t forget that you can request films to be added to Netflix by using this form here – if everyone started requested films from the 1940s consistently for three months, Netflix would be foolish not to listen.

That’s the same reason why you should also sign this petition to Keep FilmStruck Alive. Launched following the news of its impending closure, the Change.org petition has been championed by such filmmakers as Guillermo Del Toro, and is currently at over 47,000 signatures and counting. Those numbers are a drop in the ocean compared to Netflix’s 140 million odd subscribers, which means that it’s very unlikely to save the site from shutting down, but it’s the kind of gesture that could prompt AT&T to remember that consumer demand for arthouse and classic titles when it implements its plans for a more consolidated streaming presence in the future. Likewise, it signals the appeal of the Criterion Collection to other streaming services, as the collection looks to find a new streaming home in the interim.

In the meantime, if you’re frustrated by not being able to find smaller titles or older titles in this every-shifting sea of streaming video, we humbly recommend adding VODzilla.co to your bookmarks – or following us on Twitter or Facebook. We’re the only place in the UK to get a comprehensive guide to what’s on where, curating and highlighting recommendations from streaming services, both to purchase and as part of subscriptions. We’ve got up-to-date guides to what classic films are available on Netflix UK, NOW and Amazon Prime Video – and, for those who are already FilmStruck subscribers, a list of the 50 films you should see before the website closes its doors. Harder to find films, like niche streaming services, need support to stay alive. We’ll continue to support them throughout November and beyond.

UK streaming services to replace FilmStruck:

Missing FilmStruck already? Here’s our guide to the other streaming services in the UK that can scratch that cinema itch:

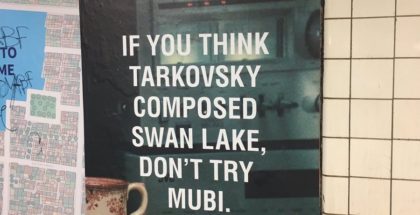

MUBI (£7.99 a month)

This subscription service operates like a carousel of classics, adding one film a day before removing it 30 days later. You can expect Bergman, Stillman, Bogdanovich, Antonioni, Fassbinder, Godard, De Palma, Rohmer, Mankiewicz, Clouzot and more. With MUBI investing in a string of “Special Discoveries” too, hand-picking new gems from emerging talent, you’ll be up to speed with the next big names to join the above list.

BFI Player / BFI Player+ (£4.99 a month)

BFI Player offers both titles available to buy and rent and, with BFI Player+, to stream on a subscription basis. The subscription library is smaller, at only 300 films, but it covers world cinema classics from Kurosawa, Rossellini and Cocteau, silent gems such as The Lodger, The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands and The Birth of a Nation, and sci-fi oldies, including The Day the Earth Caught Fire and Godzilla.

Curzon Home Cinema / Curzon12

urzon Home Cinema has swiftly become one of the go-to places for day-and-date arthouse and indie releases, thanks to Curzon also being a distributor, through its Artificial Eye label. Deals with others, such as Arrow Films, mean that you can rent new theatrical titles without having to wait. There’s also its new subscription service, Curzon12, which curates a dozen titles from its back catalogue on a monthly basis, available to anyone who’s paid for a Curzon Membership,

FilmDoo

FilmDoo is an invaluable pay-per-view platform, boasting films from around the world that wouldn’t otherwise find a home. Dedicated to picking titles from film festivals, its collection of around 800 movies range from indie titles you may have heard of (Andrew Haigh’s Weekend) to international gems such as Thailand’s Fathers, which are unavailable anywhere else.

Shudder (£4.99 a month)

AMC’s subscription service is the place to check for new and old-school horror titles, whether it’s a slasher, a supernatural thriller or sheer gross-out gore.