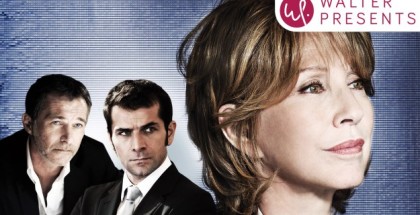

Walter Presents TV review: Spin Season 1

Helen Archer | On 10, Apr 2016

After our initial review of Spin’s opening episodes, we catch up with the rest of Season 1. Warning: This contains spoilers.

While the prize-winning French drama Spin seemed to tick all the right boxes when it debuted on More4 in January 2016 – political intrigue mixed with affairs of the heart, overshadowed by the threat of terrorism – the first, six-part season ultimately felt like more of an amuse bouche than a main course. While it gave us an insight into the morality-lite world of spin doctors and the politicians they serve, it was almost entirely without humanity or – crucially – anyone to really care about.

Opening with a suicide bombing targeted at the French president, wounding him fatally and plunging a country into fear and recrimination, the set-up was strong. As those who benefitted from a country in turmoil were quick to take advantage of the situation, it was left to the opposition to uncover the truth of the attack and attempt to restore calm.

It turned out that this was no organised terrorist attack, but a mentally ill and desperate man, acting alone. This fact was soon discovered, and covered up, by the Prime Minister, Philippe Deleuvre (Philippe Magnan) and his team, including his spin doctor Ludovic Desmeuze (Grégory Fitoussi, playing against type as a morally bankrupt, “toxic” cad).

Enter Simon Kapita (Bruno Wolkowitch), former spin doctor partner of Ludovic, pulled away from his exciting job at the UN in New York for the funeral of his close personal friend, the President. When Kapita is made aware of what everyone constantly refers to as the “state falsehood” (possible Spin drinking game – take a drink every time someone utters this phrase), he is convinced to stay and fight for the good guys, and expose the lie behind the bombing. Kapita persuades Anne Visage (Nathalie Baye), the late President’s mistress, still grieving for her lover, to run for Prime Minister.

This being France, everyone seems to have both previously worked with (and slept with) everyone else. Ludovic’s current squeeze, Valentine (Clémentine Poidatz), had an affair with Kapita, which led to the breakdown of his marriage (though, to be fair, it seems as though she wasn’t his only extra-curricular activity); Ludovic bought Kapita out of his business and seems to have some sort of Oedipus complex as far as his former mentor is concerned (hopefully, in the second season, Ludovic will make a play for Kapita’s ex-wife); not happy with taking Kapita’s business and bedding his ex, Ludovic also wants to professionally crush him. It’s all très audacieux, in a specifically Parisienne way.

Halfway through the series, Kapita’s ex-wife Appoline (Valérie Karsenti), a journalist, goes to Mali to interview the only witness to the bomb: the man who was left literally holding the bag of the bomber, the only person who knows the bomber’s real (non-jihadi) motives. Unfortunately, Valentine, who now works for Kapita, lets this slip to Ludovic during some pillow talk, and Ludovic sees to it that Appoline is thrown into a Mali jail for a few hours, the one recording (yes, there was only one copy of this very important tape, no back-ups, and certainly no computer evidence – it wasn’t quite recorded onto VHS but it may as well have been) destroyed by the authorities. The witness, meanwhile, makes it back to French soil, protected by special security agent Gendre (Abdelhafid Metalsi), only to be swiftly discovered and mown down in the street, barely mourned, and never spoken of again.

The rest of the season involves beautiful French apartments, bugged hotel rooms, suicide attempts, private jets and references to Mitterand’s meeting with Chirac in 1981, which probably makes it sound more exciting than it is.

The problem is that, despite the political machinations, the formations of strange and unlikely alliances, the betrayals and backstabbings and schemings, there are no real moral conundrums – everyone is just willing to do what it takes to get to the top. The only person with anything resembling a conscience is Appoline, and she, like the poor, dead witness, is pretty much dispatched mid-season, seen again only to serve Kapita divorce papers and to stare sadly at a TV screen. The programme also seems keen to take itself very seriously – there is no humour, just old, grey, French men being very touchy feely and assuming their attractiveness to women less than half their age, before threatening to destroy one another politically outside their ex-lover’s hospital room (très Francais).

It is perfectly normal in a political drama for no one to emerge politically or socially pristine. What generally drives the tension, though, is that characters will have their morality challenged, or are driven by something other than professional ambition. Not so in Spin. Each and every camp resorts to dirty tactics without a second thought.

“It was a sickening campaign. For me, spin has always been about conviction,” says Kapita, towards the end of the season, mourning the days when spin doctors were spurred on by real progressive, uncynical beliefs (no, me neither). The people doing it now, he continues, are “businessmen and products”. While this may be something Spin sought to highlight, as entertainment, it sadly falls into the same trap.