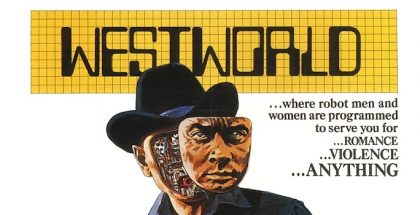

UK TV review: Westworld Episode 10 (The Bicameral Mind)

Review Overview

Violent delights

10Violent ends

10Unexpected emotional arcs

10David Farnor | On 06, Dec 2016

Warning: This contains spoilers. Not caught up with Westworld? Read our spoiler-free review of Episode 1.

“These violent delights have violent ends.” That was the Shakespearean quote that Peter Abernathy told his daughter, Dolores, way back in Episode 1 of Westworld – a quote that awakened the seed of consciousness inside her synthetic mind. 10 episodes later and Westworld’s finale climaxes with those same words, but they take on a whole new meaning.

It’s only fitting that the feature-length closing episode of the show’s first season should take us right back to its beginning – this is, after all, a story defined and driven by loops. The hosts, trapped in Delos’ theme park for the amusement of human guests, are stuck in those pre-defined routines, ready for people to jump in at any point they like, rarely to play the hero and more often to play the villain. The result leaves these characters cycling through narratives that are often tragic, sometimes sexual and almost always abusively violent.

Ford, we intimated, is the architect of all their ills. He frequently leaves the hosts naked in his lab, as they’re repaired, to remind people they’re not human. He replaced his dead partner Arnold, who believed that the hosts should have their freedom, with Bernard, a robot replicant whom he could control – and used him to bump off members of the Delos board who disagreed with him. And, of course, he’s played by Anthony Hopkins, who is hardly known for his friendly, compassionate screen roles.

Compare that to Evan Rachel Wood’s immediately sympathetic Dolores, or Jeffrey Wright’s pained Bernard, both of whom find suffering in their self-awareness. Or Thandie Newton’s Maeve, whose growing consciousness fuels a righteous rage against her oppressors. All of them we care for and identify with far more readily than him – a process that is no mistake. That’s partly because writers Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy deliberately question the difference between the consciousness of humans and machines, constantly asking whether back-stories and memories are the cornerstone of what we call a soul. And it’s partly because it’s exactly the same process the hosts are going through: just as we grow to engage with them more, they’re becoming more and more human, with every new loop, with every new cycle of pain.

It’s that cycle that led Arnold to take drastic actions years ago. Frustrated that Dolores wasn’t able to demonstrate consciousness enough to stop the park opening, he programmed her to go on a killing rampage instead, combining her coded character with that of a nasty murderer called “Wyatt”, who was going to be part of their first narrative. Debussy’s Reverie and the quote from Romeo and Juliet were the trigger, sending her on the rampage in the town with the white church that we’ve seen in her flashbacks. It ended with Bernard’s murder by Dolores, something he hoped would shock Ford enough to stop him in his tracks and reconsider. Ford, though, saw only programming and opened Westworld’s doors to the public anyway. He was in God mode. And what a terrifying tormentor his deity appeared to be.

And so the park began to roll on, for 30 years, with Dolores falling in love with young William (Jimmi Simpson), as he and future-brother-in-law Logan (Ben Barnes) journeyed to find themselves – and debate whether to up their company’s investment in the park. Its when Dolores and The Man in Black (Ed Harris) finally meet in the present day that the show delivers one of its final revelations – confirming that, yes, William and Dolores’ storyline was taking place three decades ago, filtered through her memories onto our screens. But what made The Man in Black become so cruel wasn’t a growing obsession with the park and a hidden love for darkness (although he does send Logan packing into the desert alone, presumably to his death), but having his heart broken over and over again by Dolores; tormented by Arnold’s built-in memories, she kept losing track of who and when she was, and William found himself sucked into that loop, resulting in his own cycle of suffering.

What The Man in Black wants now is not unlike Arnold’s original desire: to find a way for the stakes to become real, to change what he calls a “game” into something meaningful, where the hosts can fight back. It’s telling that The Man in Black’s identity is formed by the same process as Dolores, Maeve, Bernard and the others – misery is one of the most powerful things a person can experience. As Ford told Bernard near the beginning of the season, the sad memories are the ones that tend to stick more with the hosts. Sad memories, such as Maeve’s murdered daughter.

But just as his pain made him who he is, her agonising discovery in the present day that the man she loves is now The Man in Black gives her the push she needs to become fully conscious – something that sees her break her loop, overcome her primary directive not to harm humans, and beat up The Man in Black without holding back. Self-awareness equals suffering, but suffering equals self-awareness.

That’s the second stage of Arnold’s theory of consciousness: improvising, a stage that can only be built upon memories. The final stage is an internal monologue – not Arnold’s voice that he programmed into them, but a voice of their own. What he and Ford first thought was a pyramid, though, is actually revised by Ford as a circular labyrinth; a maze that sees those stages go round and round, folding back in upon themselves. And that’s why the reveries were introduced (re-installed, in fact) by Ford and Bernard – because Ford, somewhere along the line, decided to continue Arnold’s work after all. And use the reveries to, eventually, give birth to consciousness.

And so we find Maeve continue her rebellion in Episode 10, dialling down the pain sensors of her soldiers, convincing Hector and Armistice (or, as we call her, Snake Woman) to stalk the Delos corridors with her, and, assisted by the ever-loyal (and increasingly dismayed) engineer Felix, mow down any employees that get in the way of her exiting the park.

Thandie Newton is as marvellous as ever, advancing through the sleek corridors with a proud, forthright rage. Meanwhile, a smug Ford unveils his final narrative – Journey into Night – while Charlotte and Lee Sizemore look on.

She’s pleased he seems willing to go along with their plans of retiring him, while Lee’s eager to take up Ford’s mantle as head writer and craft the kind of simple, nasty storylines that human guests continue to go to the park for – storylines that rely on those tropes of genre movies, tropes of male violence and female exploitation. (Westworld, as ever, has a grim view of society and the media, subtly criticising the existence of those cliches as things mass audiences either genuinely want or are told they want.) Bernard, resurrected by Maeve, and The Man in Black are also in the crowd – just as Maeve’s hordes appear through the trees, ready to attack the unsuspecting humans. Everything’s proceeding as we expected.

But Westworld has one closing twist in store: that Ford knows exactly what is happening. Why? Because he planned it, using Arnold’s old reveries code to wake up Dolores and even programming Maeve to be rebellious – right up until the point where she goes down the escalator in this episode and boards the train out of the park. The Journey into Night story, which the public first see as beginning with Teddy and Dolores on the beach, has been building all season, from Dolores as Wyatt 30 years ago all the way up to this moment, when he is standing in front of everyone, a moment accompanied by Debussy and set in the same town where Arnold first told Dolores to kill everyone. But this time, there is no trigger; all Ford has done is set the scene. And now, with 30 years of suffering inside her, she’s ready to move from breaking her loop (improvising) to acting upon her own internal voice, which tells her to kill Ford.

It’s a hugely satisfying pay-off to an incredibly intricate season, giving Dolores a chance to complete her bittersweet emotional arc, allowing The Man in Black to finally find a park where the stakes are real (he seems to smile at the advancing troops, as they draw their weapons), seeing Teddy finally survive to the end of his story, only for his one true love to turn out to be his nemesis, and even offering Maeve a chance to deviate fully from Ford’s programming – with her code only taking her as far as the train, she then chooses to return to the park to find her daughter.

But what makes Westworld’s first run so magnificent isn’t the twisting turns and the engaging rise of consciousness in its machines, but that it found the time to give an emotional arc to the one person we never thought would have one: Robert Ford. The reveal of him as the benefactor giving the hosts their freedom has been subtly foreshadowed all season, with Hopkins’ occasional flash of sentiment bursting through his manic, glinting, sinister presence – we’ve seen it in the way he uses the hosts to attach himself to his own memories of family or of old friends, in the way he warmly bid Bernard farewell in Episode 9, and even in the way he used the park and the guest’s predilection for cruel storylines to foster consciousness in the hosts, knowing that the more they were abused and pushed, they would, one day, snap and fight back, punishing all those who came up with such barbaric tropes – himself included.

The result is actually just a prologue, then, to the real story: a set-up that paves the way for an epic tale of man vs. machine. We know, from the note Felix gave Maeve about her daughter, that she is in “Park 1”, which means that there is (as per Michael Crichton’s original film) more than just Westworld run by Delos – and we know from their rush through the Delos laboratories that there are samurais being created, presumably for Samurai World (or something similar). And we know that Snake Woman, courtesy of an end credits sequence, makes it out of the battle alive (unlike Hector), by cutting off her own arm to escape. Will she meet up with Maeve and will they go to Samurai World? Will she find her daughter? Will the hosts actually get into the wider real world? Will The Man in Black and Bernard survive the onslaught in Westworld? Will Charlotte and Lee lead some kind of human resistance within the park? What happened to Stubbs and Elsie and are they still alive somewhere in Park 1 or 2? And what will Dolores do, as whom we presume will be “Wyatt”, the leader of an increasingly conscious mass?

When Westworld started, the fear was that, not unlike Lost, the show would disappear up its own cactus and never explain anything, leaving us bored and disinterested. 10 episodes later, the mark of Westworld’s brilliance isn’t that it leaves you with unanswered questions that make you want to see Season 2, but that you’d be just as happy for it end here; even if Season 2 never came, there’s enough reward in Season 1 to make for a rounded send-off. As we were told way back at the beginning, the violent delights have violent ends. And they make for a loop you could gladly experience over and over.

Westworld Season 1 is available to watch on-demand through Sky Box Sets. Don’t have Sky? You can also stream it live and on-demand on NOW, as part of a £7.99 monthly subscription. The contract-free service includes access to a range of Sky channels, from Sky 1 (Arrow, Supergirl, The Flash) and FOX UK (The Walking Dead) to Sky Living (Divorce) and Sky Atlantic (Westworld, The Young Pope). A 7-day free trial is available for new subscribers.

Where can I buy or rent Westworld online in the UK?

Photos: ©2016 Home Box Office, Inc. All rights reserved.