True Crime Tuesdays: The Innocence Files

Review Overview

Detail

10Injustices

10Emotional impact

10Helen Archer | On 30, Jun 2020

On Tuesdays, our resident true crime obsessive gets their fix with a documentary film or series. We call it True Crime Tuesdays.

It’s not just the length of Netflix’s latest true crime series that makes it a behemoth of documentary-making, but the amount of information contained within its nine episodes and its sheer ambition. While much true crime involves the details of the felony itself, and the impact on both victims and accused, The Innocence Files weighs the human interest with a forensic look at the fundamental failures of the US justice system. But more than that – it busts the myths of what has previously been seen as “watertight” evidence, and offers solutions to help fix a corrupted system.

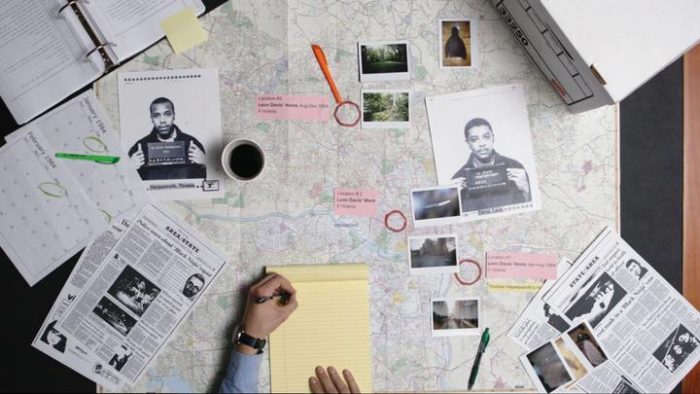

Split into three sections, directed by doyens of contemporary true crime programming, this is not your generic binge-watch. So much is packed into each episode that it does good to take your time and let the information settle before allowing the next to autoplay. Structurally, it splits into different aspects of criminal justice – evidence, witnesses, and prosecution – and focuses on a case per episode (though some are connected) to look at people who have been sent to prison, sometimes for decades, on the back of false evidence.

The Innocence Project is the thread that weaves their stories together. Founded in 1992 by Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, it’s seen as the “court of last resort”, and receives hundreds of letters per year from all over the US, written by people claiming to be wrongly convicted. They are only able to take on around 1 per cent of such cases, and these are some of the “successful” ones.

The current criticisms of policing practices and demands for judicial reform in the US adds this series an extra air of urgency and relevance, which it may not have had when first released on Netflix, a mere two months ago. It almost goes without saying that the majority of the men featured here are African-American. Two are white, one is Hispanic. Their stories are remarkably similar, as are the portraits of the different parts of America, with confederate statues standing proudly outside court buildings, and prisons linked to slavery and plantations.

The first three episodes, by Oscar-winning director Roger Ross Williams, look at junk science – the various unreliable methods used in evidence against an alleged criminal. The “CSI effect” is said to have legitimised everything from hair follicle matches to footprints and tyre prints – and yet such “science” is deeply flawed, even as people have made profitable professions of their “expertise”. Ross Williams focusses specifically bite-mark evidence, used to incarcerate two separate innocent men for the child murders someone else had committed, while the final part of the trilogy looks at how the same unapologetic “expert” featured in the first two episodes was integral in putting another man behind bars for a rape he didn’t commit.

The second section deals with witness testimony, and the myriad ways in which this can fail, be it through coercion of witnesses, manipulation of line-ups, or through flaws which are built in to the system. The incarceration of Franky Carrillo, who was falsely identified as a drive-by shooter, demonstrates corrupt police work, while Liz Garbus directs an episode that details how the wrong man was found guilty of a series of rapes. The way in which people process trauma is but one of the explanations behind false identification – problems of inter-racial face recognition also play a part.

The final three episodes – the first of which is directed by Alex Gibney – look at unscrupulous prosecutors who will do anything for a result, even if it means withholding evidence and deliberately sending the wrong people to prison. In each trilogy, whether dealing with “experts”, detectives, or prosecutors, their own potential reputational damage overrides justice, with tarnished careers seen as a fate worse than the incarceration of innocent people.

The Innocence Files is serious yet accessible, powered by a righteous yet not over-the-top anger, and it hopes to change things – or at least open people’s eyes to the things that need to change. Despite its detail, though, it feels as though it’s merely scraping the tip of the iceberg. What stays with the viewer are small moments caught on camera. Whether it’s Chester Hollman staring at the prison he’d spent 28 years in, from the other side of a bridge he thought he’d never cross, or Levon Brooks spending the last few months of his life a free man, looking after his chickens and working on the art which helped him survive his 16 years in prison. The mothers and fathers who died fighting, without living to see justice for their children. The terrible tragedy of lives, stolen.

The Innocence Files is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.