The Crown Season 4 review: Royal drama raises the bar

Review Overview

Cast

8Hair

9Themes

8David Farnor | On 14, Nov 2020

This is a spoiler-free review of The Crown Season 4, based on all 10 episodes of The Crown Season 4.

“First and foremost, I’m a wife and a mother,” declares Princess Diana (Emma Corrin) in Season 4 of the Crown. It’s a key line from the the first wife of Prince Charles (Josh O’Connor), as she seeks to reinforce her identity – and her priorities – in the face of enormous political and personal pressure.

Peter Morgan’s royal drama has repeatedly mined the gulf between the public and private to chart the life of Queen Elizabeth II, a life that was thrust into global view when she was crowned at the age of 25. This season’s dig into the nation’s past is the most richly rewarding yet, as the territory draws closer to the present and closer to a tragedy that many viewers will still remember within their lifetime. That’s partly thanks to Olivia Colman’s sterling performance as the long-reigning monarch, building upon the exceptional turn from Claire Foy in Seasons 1 and 2, but it’s also because Season 4 introduces so many other key players to the stage, and the ripples that these modern figures spread are riveting to watch.

Princess Diana’s shadow has always loomed large over The Crown, and it’s remarkable just how well this season lives up to that anticipation. Emma Corrin is sensational as the young princess, an idealistic girl excited to meet Charles and soon swooped up in the potential of being his wife. She thrives on the outpouring of affection and attention that ensues, as much as she’s wary of it – she undercuts every public appearance with her coy side-glances – and she pours herself not only into the public’s hearts but also into looking after her offspring – torn between her personal life and her professional obligations.

The very notion that she could put her new son, William, above the requirements of the royal family is enough to put the rest of the family’s noses out of joint – especially when they resent and crave the kind of love she inspires from their subjects. For Princess Anne, someone who has consistently kept herself away from press scrutiny, the apparent ease with which Diana’s charm and beauty captures the UK’s imagination is enough to turn her sour, while even Prince Charles struggles with the notion that his partner is going to upstage him at every official occasion. Princess Margaret (Helena Bonham Carter), meanwhile, is as withering towards her as she is to any outsider who dares come near.

But underneath all that resentment is a simple envy of Diana’s emotional sincerity, an attachment to her son above all else that, contrary to accepted wisdom, endears her to the public further. It’s the kind of open-hearted concern that Elizabeth has never shown her own kin; while Diana is a wife and mother first and foremost, the Queen has been raised to put the Crown above all else, and that cool, repressed manner has instilled a frosty detachment throughout her dysfunctional household. The very notion that someone could come into their world and not follow suit, instead behaving like a normal person, rankles all of them.

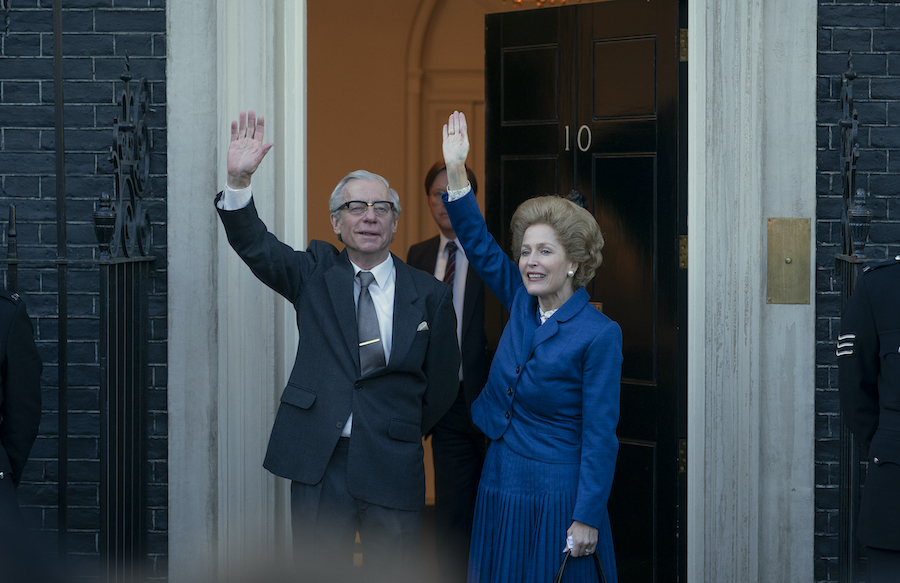

Season 4 doubles down on that idea of interlopers upsetting the norm with an elegant dovetailing between the intrusion of Diana and the rise of Margaret Thatcher. If Emma Corrin inhabits the role of Diana with a beguiling charisma and confidence – an evocative solo dance sequence set to Blondie is one of the boldest things The Crown has done to date – Gillian Anderson disappears into the role of Margaret Thatcher with an uncanny accuracy, capturing the rasping vocals and steely resilience of Britain’s first female prime minister. Both are helped by flawless costume design and impeccable hair; the trimmings enable the actors to do more than just impressions, bringing humanity and nuance to their recognisable faces.

That’s particularly obvious in one standout episode that sees Margaret visit Balmoral, where she and her husband, Denis (a delightfully loyal Stephen Boxer), fail every test set them to try and fit in. Meanwhile, Diana equally slips up when it comes to curtseying and using the appropriate titles, but manages to breeze through it with a warmth and innocence that Thatcher has long since put behind her. We’ve rarely gotten to spend so much time with people outside of Windsor or Buckingham Palace, and Season 4 consciously uproots us to the wider world, including Diana’s days renting in a flatshare, once again allowing us to see the royal family not as they see themselves, but through the lens of how others see them.

Their snooty exclusiveness may be an obstacle for both Maggie and Di, but it isn’t a challenge for a burglar, Fagan, who famously breaks into the Queen’s London residence at the season’s precise midpoint – the closest thing The Crown has to a bottle episode and one that spends half of its time waiting in job centre queues, as it spells out the devastating consequences of Thatcher’s austerity-driven policies. Fagan, we learn, just wants someone to listen to him, and when that person turns out to be the Queen, he doesn’t falter – it’s quietly poignant that the Queen’s apparent eagerness to give an ear to a member of the public displays more care and concern than she’s ever shown to her own blood.

It’s fascinating to see Olivia Colman’s Elizabeth grappling with these contradictions, and Season 4 sees its protagonist really grow into a complex character. Positioned elegantly next to Claire Foy’s still-resonating stoicism, Colman’s older matriarch has turned that facade into her persona at all times, but perhaps for the first time begins to see herself as others do. One of the most amusing, endearing and heart-wrenching moments comes when Prince Philip asks her who her favourite child is – his playful prodding of her unflappable exterior not only shows how well he knows her, but also challenges her to voice feelings that she’s consciously buried for so long that she isn’t even sure herself.

Tobias Menzies has made Matt Smith’s shoes all his own over these past two seasons, and he delivers a masterclass in finding maturity amid a petulant family. He manages to be affectionate, reserved, self-aware and imperiously intimidating, often all at the same time. Perhaps more than anyone else, Menzies’ sharply dressed Philip understands exactly what is required of him in his role and has made peace with it. His scenes with Princess Anne, before and after a nervous equestrian tournament, are as tender as his moments with Diana during a key party, even as he goes on to scold and warn Charles’ wife about what lies in store.

If Elizabeth and Philip’s hard-won contentment is a joy to see reach full bloom, Season 4 neatly parallels that with the torment of Charles and Diana, who repeat their feat of touring Australia. With William in tow, what Elizabeth and Philip hope will be a trial that pushes them closer together instead becomes an excruciating crucible that heats up their divisions further. The ever-present chemistry between Emerald Fennell as Camilla Shand and Prince Charles only makes the reality grimmer to observe – a dinner scene between her and Diana is as painful as Diana’s private eating sessions, which are unflinchingly but sensitively depicted. In between them, Josh O’Connor excels as Charles, radiating immature entitlement and thoughtful selfishness from his toes all the way up to his hunched shoulders. O’Connor embodies Charles so seamlessly that even his ears deserve awards – in two seasons, he’s turned the likeable boy who would be king from a sweet antihero to the least sympathetic person on screen.

Anderson, by contrast, humanises Thatcher in a way that would be surprising in any other context. We see Maggie facing down the fierce hostility from others in her own party, yet also cooking food for the cabinet at her house. An attempt to tie together her fears about her missing son with her determination to keep hold of the Falklands isn’t exactly subtle, but it again positions her as a mother as well as a politician, and that only makes the differences between her and the Queen more striking. The scenes where they meet for a few minutes every week are electric, as we get to see Colman and Anderson go head to head – one brief moment of vulnerability aside, it’s a barbed clash of principles that’s utterly gripping.

In the same way that Diana isn’t portrayed as a victim or villain, just a young woman thrust into a messy situation with messed-up people, The Crown crafts provocative suspense by refusing to make Maggie a pure and simple enemy, with her and Elizabeth both able to expose each other’s weaknesses – the Queen’s reference to the Commonwealth as her “family” is all too telling.

With all the time spent on Thatcher and Diana, the other members of the ensemble get somewhat short shrift. An opening chapter involving Charles Dance resorts to an on-the-nose hunting metaphor to set up its themes, leaving less time to explore Lord Mountbatten’s role as a father figure for Charles. Princess Margaret, meanwhile, has a melancholic episode that sees her grapple with depression, but moves from a scene-stealing sideshow to an under-used sidekick.

But there’s a neat triangle of themes at play here, as The Crown juxtaposes its central female figures: Thatcher, with a vision for the country’s future, Diana, with the potential to embody the royal family’s future, and the Queen, who is focused on maintaining the traditions of the past. That smart examination of three important forces that shaped the history of the nation and the royal family helps the show to avoid superficial melodrama, even as it becomes more soap operatic than ever – combined with its lavish cinematography and stylish editing, it feels less like it’s dressing up history as prestige TV and more like it’s living up to a larger-than-life legacy.

Throughout, the thing that ties these women together is a stubbornness that their way is the right way to approach their positions. Anderson’s Thatcher has a chilling certainty in her ideology that harsh treatment is needed to “cure” society’s problems, and that gritting one’s teeth through the pain is necessary to make things better. The Queen, according to Morgan’s portrayal, disagrees with Thatcher’s chosen medicine (having witnessed its cruel results), but she also believes that grinning and bearing with one’s personal anguish is the path to eventual happiness – a belief that she’s pushed upon her children. In the words of Philip Larkin’s This Be The Verse, half the time they’re soppy-stern and half at one another’s throats. The result is misery that breeds resentment, and it paves the way for the tragedy we know is only another season away. The Crown just raised the bar even higher for its next generation.

The Crown Season 1 to 4 is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.