Auteur for hire: The ‘real’ world of Kiki’s Delivery Service

Simon Kinnear | On 01, Feb 2020

With Studio Ghibli films now available on Netflix UK, we look back at what makes them so magical.

How do you tell a true auteur apart from other directors? Not by the passion projects they dream into being, but by the work they take under necessity. Famously, Studio Ghibli boss Hayao Miyazaki was never meant to direct Kiki’s Delivery Service. Already hard at work on My Neighbour Totoro, he assigned alternative screenwriters and directors, until things (as he diplomatically puts it in an interview on the Blu-ray) “fell apart”. So he stepped in, first writing the screenplay and ultimately directing it.

The result is among the most interesting of Miyazaki’s films for the tension between its atypicality and the way he invests the material with those undeniable flourishes of his. On one level, it’s practically a checklist of things you expect to see in a Miyazaki film: flying; fantasy; a young heroine. And yet it’s the inverse of so many Miyazaki classics. Unlike My Neighbour Totoro or Spirited Away, when normal girls enter the dream world of Miyazaki’s imagination, here the narrative concerns a witch’s efforts to get by in the real one.

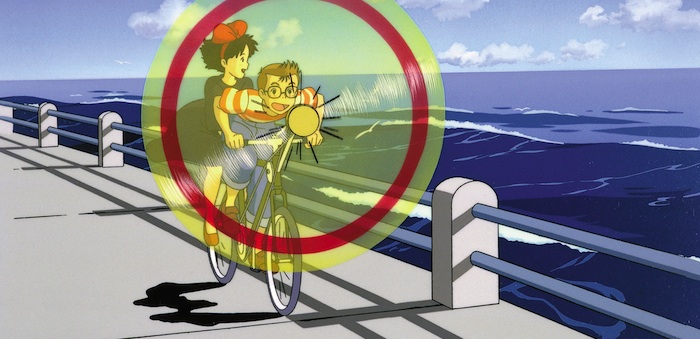

© 1989 Eiko Kadono – Nibariki – GN

Realism isn’t a word that is commonly applied to Miyazaki, which is why so many reviews of his recent swansong The Wind Rises listed it as a departure. That’s not strictly true, of course – Miyazaki wrote the screenplay to teenage romance Whisper of the Heart, a film of gorgeous verisimilitude and Studio Ghibli’s hidden masterpiece. But Miyazaki didn’t direct it himself, entrusting to his protégé, the late Yoshifumi Kondo. Tonally, that film would sit oddly alongside the outright fantasies of Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind, Princess Mononoke and the rest. Yet, among the films that Miyazaki directed, its closest companion is Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Forget, for a minute, that Kiki is a witch. That’s actually easy to do, because Miyazaki pares back the mythology to the barest of essentials: a broomstick, a black cat and an arcane tradition that, on turning 13, a novice witch must take a gap year to train herself out in the big wide world. That’s it. The only other witches we see (members of Kiki’s family, another trainee passing by) are gone within the first 15 minutes. Otherwise, it’s just Kiki, and Kiki wants, perhaps needs, to downplay her credentials in order to fit in. In every other way, she’s a typical teenage girl, aloof with the boy she fancies and yearning to buy pretty clothes.

Kiki’s Delivery Service

© 1989 Eiko Kadono – Nibariki – GN

It would be so easy to have made this film an action-packed adventure in which Kiki’s powers manifest themselves as something mysterious and magical to help the people of her adopted town. The nearest the film comes to that witch-as-Superman plotline is in its startling climax – a variation on the scene in the 1978 Superman film when he rescues Lois Lane from a stricken helicopter – but even that achieves its emotional impact thanks to its metaphorical value of restoring Kiki’s faith in herself. Instead, there is a brisk matter-of-factness to her abilities; they are utilitarian, a source of income as much as power.

The result, as the title implies, is a film about starting a business, run by a shy teenager in need of a confidence boost. There are no weird creatures and no complex narrative; the story is simplicity itself – naïve, even, in its childlike innocence, given what calamities might befall a 13-year-old girl arriving in a strange place with no friends and no accommodation. The wisps of plot would probably wither without the detail that Miyazaki invests in them in order to suspend our disbelief. Kiki’s mercurial shifts between disorientation, panic and exhilaration are captured by the sheer density of texture in Miyazaki’s depiction of the ‘real’ world, with its bustling crowds, traffic and richly-detailed buildings.

Note: that’s ‘real’ in inverted commas, because Kiki’s workplace is no-place. The basic model is the Swedish town of Visby, a place Miyazaki had visited and loved – but, famously, he never went back during pre-production, preferring his memories to the physical facts of its geography. That enabled him to mix in elements of other cities (a bit of San Francisco here, parts of Paris there) to create a hyperreal, idealised vision. It is a stunning achievement, and a testament to Miyazaki’s imagination, that ranks alongside his more overtly fictional story worlds.

Similarly, Miyazaki deliberately toys with our sense of time. Microwave ovens and live news feeds suggest the modern day, yet black-and-white television sets and the dirigible that becomes central to the film’s climax are from a much older age. It’s the same post-modern trick that David Lynch pulled off in Blue Velvet, albeit to the opposite effect: not to bewilder us, but to comfort us, creating a sense of benign timelessness.

© 1989 Eiko Kadono – Nibariki – GN

By controlling time and place, Miyazaki removes all conflict and tension from the narrative, which means everything rests on Kiki. In doing so, he creates a character whose crises are psychological, a youngster determined to live up to tradition and her own high standards, yet still finding the maturity to control her emotions. She is variously defiant, petulant and self-pitying, yet there’s a core of ambition and kindness that overwrites her flaws. Miyazaki goes to the trouble of including a lengthy scene where Kiki goes out of her way to help an old lady bake a cake for her granddaughter’s birthday, only for the latter to be revealed as a spoiled brat unappreciative of the time, love and hardship involved in preparing and delivering her gift. That girl is the anti-Kiki, yet Miyazaki is so warm-hearted that this character, the nearest to a villain the film has, is hardly in it.

Kiki’s biggest setback sees her losing her powers, a self-inflicted defeat brought on by neurosis. It’s the most atypical thing in the film (a director, who is known for fantasy, getting rid of the fantasy entirely) but that’s precisely the point: the auteur defining himself by the absence of auteurist elements. Revealingly, Kiki befriends a painter, who helps her overcome her despair by admitting that she, too, gets blocked sometimes. The profession isn’t a coincidence. The painter talks of how she struggled to find her voice, of how she had to learn to stop copying others and find her own style. Suddenly, this work-for-hire becomes personal, pertinent and something that only a true auteur would create.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.

Note: This was originally published in 2014. For our full Studio Ghibli retrospective, see The Magic of Miyazaki.