Interview: Nev Pierce talks Promise, jumping from journalism to short films and impressing David Fincher

David Farnor | On 19, Aug 2018

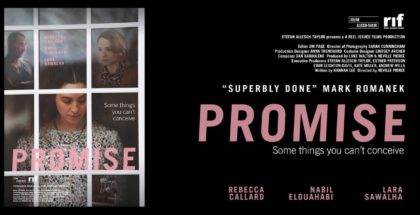

This summer sees the release of Promise, a new short film from Nev Pierce. A film journalist turned writer and director, his work has won praise from David Fincher and Mark Romanek, and starred everyone from Tim McInnerny and Jason Flemyng to Alice Lowe.

Promise is a moving adaptation of Genesis 16 for the modern day, telling a story of a couple and their relationship with a Syrian refugee. (Read our review here.) We chat to Nev about making connections, jumping from film reviewing to filmmaking and putting a script in front of David Fincher:

Going back to Bricks and Lock In, there’s a vein of social realism in your work that feels very rooted in your stories’ surroundings.

That’s a very nice thing of you to say. This is a really unglamorous answer: I just think of how difficult it was to find the location! Part of that is you’re looking for something that’s practical, but also the catch is the mood and the space you can work in, and also something that matches what’s in your head. Especially with Bricks, I think… because I’d been trying to make films for such a long time and Bricks was the first one, I felt (and a lot of this was probably imagined pressure – because ultimately, who cares?) ‘I’ve got to make it brilliant, it’s got to the best it can possibly be, because I’m a film journalist becoming a filmmaker, so I only get on shot at it’. So I was very specific and very picky about getting the right space – and ended up pushing production several times because of it, and also because of issues getting the actors.

I think that’s one of the things you look for in a short film, right, because usually, you have a limited budget, so with Bricks, it was very much ‘What sort of story can I tell in a confined environment?’ – then, that idea came to fruition when I discussed it with Jamie [Russell], who I wrote it with, who mentioned the Edgar Allan Poe story, which I’m presuming I must have read as a teenager and just subconsciously ripped off, and yeah, you just find all the things you can layer into it. I don’t know if that answers the question!

Promise must have been a bit of relief then, being shot mostly in a home

You’d think so! [Laughs] The issue with that was finding a house where we could use the whole house within the M25 where people were flexible enough to give us the time we needed. We scouted a few places and it ended up that Susannah knew one of the producers and offered her house and we were fortunate to get it. Making it I was reminded – and this is tonally very different – but I remember interviewing Fincher about Panic Room and people thinking shooting it in one house is the easy way. But no, it’s a nightmare! The scene in Promise where Lara is throwing up in the bathroom, I am crouched in the shower with a monitor about 3 inches from my face, trying to make sure the sick is the right consistency, thinking ‘How many takes can I do before Lara says ‘I’ve had it’?’ No one complained. All the actors were fantastic.

Promise is written by Hannah Lee – do you prefer writing and directing, or just directing?

I think I write in order to direct. It’s not so much about writing the story as it is about telling the story, so it doesn’t necessarily have to be one I’ve originated, just something that you just feel the urge to go with. That sounds incredibly pretentious! I’m a judge on a competition called The Pitch and Hannah had pitched it, and she hadn’t won that year but she was in the top three, and I just thought: ‘This is something that needed to be out there in the world. If the only way for that to happen is me to direct it, let’s see if I can raise the money to put it together.’ I couldn’t tell you why that was: it was only really on set that I realised in a conversation with an actor one of the main reasons I was making the film, which is not something I can reveal. It’s related to a feature I’ve written, but in a way I hadn’t really realised. In the limited time I’ve been making films, I’ve learned don’t question it too much, just follow your nose. Don’t strategise too much. It doesn’t mean you should have a devil-may-care attitude, but every time I’ve tried to game the system, you just fall on your arse. You should just do the thing you’re passionate about.

I’ve had a couple of people going ‘Why are you making a short drama about an asylum seeker based on a Bible story?’, with kind of the implication of what’s wrong with me, but I don’t know, the story’s just compelling to me. And I’ve been looking to do something with Renecca Callard for a while. I think we just got to know each other through Twitter and I thought she was terrific. I think there are sides to her ability or personality that have not been fully explored in the stuff I’ve seen on screen. She’s terrific, but she’s got a whole spectrum of things to offer, and when Hannah spoke about the story, I thought about Rebecca and thought she’d be really good for this.

How about Nabil?

You know what? I really can’t remember! I think I was just idly doing a Google search looking for actors and his name popped up and I thought ‘He’d be great’, and I contacted his agent. Nabil saw I’d worked with Nicholas Pinnock [on Lock In] and he knew Nicholas and knew he was quite particular about who he worked with, and then we met and got on well. He did a bit of schedule juggling and he came on board with it. It was Nabil who recommended Lara, because they’d done stage work together. I got an email the day after I met him saying ‘I understand you’ve got a short film…’ and that’s very flattering, when an actor says to a friend ‘Oh, you’ve got to get involved with this’. And I met Lara and I thought she was tremendous… it’s very hard to do these interviews without just gushing! [Laughs] It’s weird being on the other side of it. The thing is when you’re doing the interviewing, you can edit yourself and make your questions seem so erudite. ‘It’s like a work of art this interview!’ Anyway, that’s a very rambling answer, but I think that covers it.

You’ve worked with people like Jason Flemyng too. How much have your journo connections helped with casting and drawing big names to your work?

I think it’s invaluable. The Flemyng I had met on the set of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I was on set for Zodiac, then that – I’ve been on set for each of Fincher’s films since Zodiac – and I hear this familiar cockney voice behind me and I turn around and I’m like ‘Why is Jason Flemyng in this Brad Pitt movie?’ I mean, obviously, they’d worked together on Snatch, but it was surprising to find he was there playing Brad Pitt’s dad. He was surprised to find a British journalist there and we got chatting and ended up, naturally, going for a few beers. I talked about the fact that I wanted to make films at some point. Bless him, he said ‘If you ever need anybody, just call me’ and gave me his email address. Cut to: seven years later. I emailed him and said, ‘Okay, I’m ready Jas.’ And genuinely he was like: ‘Great, yep, let’s go.’ We had to juggle a bit, as he’s got features and stuff. He’s a stand-up guy, one of those people who has never lost his enthusiasm for what he does, and is super grateful for what he does. And that helps to have him, you’ve got somebody who’s really good quality, so then if you approach other people, it’s like ‘We’ve got this actor involved’. And that then can snowball – basically what happened with Nabil. Nicholas Pinnock I’d met at Wellcome Trust drinks and we just got on really well, and he gave me some really good personal, life advice, and when Lock In came up, I thought it might be something for Nicholas. So you absolutely do use every connection you’ve developed as much as you possibly can.

It’s a funny thing, this film journalism thing. It’s absolutely a blessing the things you learn and the time you spend with great filmmakers. I think it’s given me a slightly warped perspective or a misplaced sense of expectation of where I should be coming into the industry: I’d had an idea for a feature film that was probably slightly too big for a feature film, and that’s because I guess, a lot of the people I was hanging around with, they made big feature films. That kind of maybe led to an unconscious arrogance? Or an over-confidence, I don’t know. Equally, it’s also amazing if you spend time with great filmmakers and try to learn from them.

You started screenwriting professionally back in 2011, around 12 years after you started working on Total Film. Was filmmaking always the dream end goal?

I think it probably was. I don’t know if I would’ve admitted that to myself. I wrote my first screenplay. No, wait, I started my first screenplay that I subsequently finished when my eldest son was six weeks old. My son is now 6ft 3 and he’s just done his GCSEs, which gives you an indication of the length of time in writing! But there are big gaps in that, you know, so I wrote that screenplay, which was a $100 million Western based on The Iliad and obviously, everybody died, which gives you an idea of a. how pretentious I was, and b. how unrealistic I was. Then I met Jamie Russell and we wrote a script together and we put it in a drawer for five years and I went to Total Film and he went abroad and he did his own thing. It was only five years later, and it was a zombie film, and the zombie movie thing just kept on getting bigger and bigger, and we took it out of the drawer and rewrote it, and that’s when I showed it to David Fincher. He was very complimentary about it, and that’s the moment I thought ‘Right, OK. I guess I can be good enough to do this’. Which would’ve been around 2010, 2011.

Showing your script to David Fincher – how nerve-wracking was that?

I think, yeah, ultimately by that point, he either likes it or he doesn’t. You know what I mean? He doesn’t like it, well, big shock. One of the filmmakers with famously the most high standards in the world doesn’t like your work, fair enough. I can’t run as fast as Usain Bolt either. There are certain things where you’re like well, OK, I’m not that upset. I’d known him for five years or so before I even told him I wrote scripts, because what I didn’t what to do was be one of those people who meets somebody and goes ‘Oh, how can you help me? How can you help me?’ We all have those people in our lives and those people are not friends; those people are leeches. And i didn’t want to be a leech. I wanted to have earned the right to have a conversation and be like OK, this is natural outflow of a professional relationship that then became a friendship, so it would be reasonable to say ‘Would you have a look at this?’ But that was the moment I thought ‘I guess I can do it professionally’.

But it’s a business of cul-de-sacs and false starts and hurry-up-and-wait. There’s, you know, times I’ve taken my foot off the gas completely with the journalism, where I’ve signed a contract and thought ‘I’m gonna make £150,000 this year’ and then the film has not been made, and you go ‘Huh, I guess I shouldn’t have tuned down that freelance work’. And that’s the weird thing about it. I guess I was a little naive in thinking yeah, I can do it now. David Fincher likes my work, I’ve got an agent, this is gonna happen, this script has been sold, I’m directing this thing, bang bang bang, it’s gonna be great. I think I’ve been very fortunate as a journalist that I’ve done quite well quite early, and maybe felt the same was going to happen with filmmaking. It turns out that’s not the case!

I think filmmaking is inherently a little bit arrogant. Like, even if you’re the most deferential person in the world, some part of you is saying ‘I have a story that deserves to be heard and you have to listen to me’. Even if you’re really soft spoken, physically unprepossessing, there is still some germ of ‘You must listen to me’ that must be part of you somewhere. I can’t remember the point I was making at the start of this paragraph…

So if someone asked you for advice on becoming a filmmaker, you wouldn’t suggest becoming a film journalist!

Oh, absolutely not! [Laughs] And I don’t know how one starts in film journalism now. There are less outlets than there were, there’s less money than there was. The way people leave staff positions on magazines is when they die. People get their feet under the table and they stay as long as they can. I think the proximity to something you love can be really useful, but I think it can also potentially stop you just taking the plunge and going for it yourself. I read an Edgar Wright interview in which he said ‘The way to make films is to go to make films’. People talk about Shaun of the Dead as his debut, but obviously, he made A Fistful of Fingers before that, which I think he refers to as his amateur film, but he still talks about it as his first film, and he just made it with his mates. There’s something to be said to just going and making stuff, and I think that is now more of an option than it used to be, making stuff without necessarily presuming it even needs to be seen. When I made Bricks, I was like ‘This has to be seen, I’m making this to a certain standard’, but if it had been 10 years earlier, and I hadn’t been a film journalist, maybe I’d have made a bunch of shorts. You know, Shane Meadows started just by doing stuff with his mates and there’s a good argument to be made that he’s our best contemporary British filmmaker. Granted, he hasn’t made a film in 10 years, but that’s painful – people should give the guy a blank cheque.

While journalism’s struggling to adapt the web, it does feel like the web is now finally catching up with short films, that there’s a more viable platform for that work now

I think it’s a lot easier to get your work out there and give it a possibility of being seen. But I think it’s a lot harder to get attention for your work, especially if you’re trying to tell stories and not do stunts or do VFX-laden shorts. Which is not to knock those things – I probably say that partly out of jealousy! I’d love to have a viral film where people go ‘Man, 100,000 people have seen this, let’s give him a picture at 20th Century Fox’, but again, you do the thing that compels you. For me, those sort of things have been thrillers and dramas that have hopefully been fully-formed stories even in 10 to 15-minute films. I don’t know that people watch a lot of short films. I don’t know that I watch a lot of short films. I don’t know what that is. There’s so much material out there. I think if short films were on Netflix or more accessible on Amazon Prime… I would hope that would happen.

So what’s next for you?

Me going over these answers for an hour and wondering ‘Did you say anything vaguely coherent?’ [Laughs] I’m debating what to do. I’ve got a couple of scripts done, one that I co-wrote, one that i’ve written by myself. I’ve got another script I’m attached to direct, which is being produced by someone I really admire. That’s early stages. As for which one is happening next, I’ve learned not to predict that!

Promise, Bricks, Lock In and Ghosted are available to watch online now on Vimeo. You can read our reviews of them here – and you can find Nev Pierce at @NevPiere.