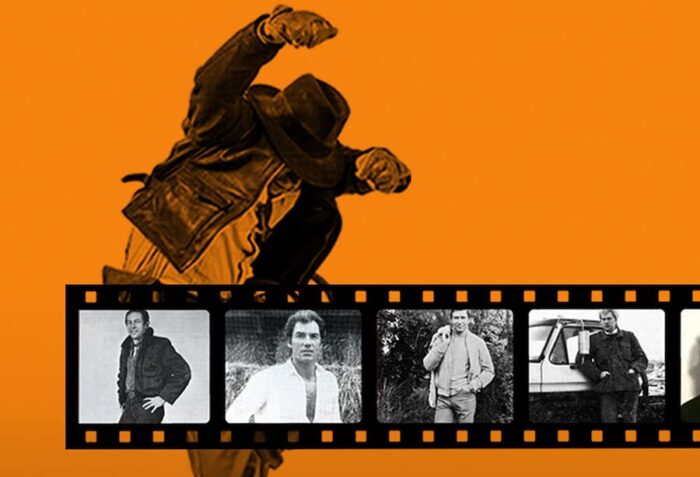

Interview: Stunt legend Jim Dowdall talks Bond, Indy and Hollywood Bulldogs

David Farnor | On 27, Jun 2021

“There are very few jobs that I’d fit into comfortably on a 9 to 5 basis,” jokes Jim Dowdall, who has been in everything from James Bond to Indiana Jones. His isn’t a name that you’ll know, but he’s one of countless unseen heroes of the silver screen, who make the impossible possible: a stunt person.

It’s not a career that he expected to end up in. When he left school aged 16, he knew he was “good at the physical stuff”. And so he joined the circus.

“It isn’t normal to be feeding tigers at 9pm or be grooming horses or whatever it was we were doing,” he admits. “I used to bring elephant poo back in the saddlebag on my motorcycle for my mother to put on our roses. She would say, ‘I’m the only woman in the street who’s got her roses grown on elephant poo.’ From there, I did a variety of jobs, then I went to work for this armourers and I worked on The Dirty Dozen.”

That was the gateway to a profession that would see Jim put his life on the line again and again. What’s alarming from the documentary Hollywood Bulldogs, which features Jim and a number of other stunt people in the 60s, 70s and 80s – from Vic Armstrong to Frank Henson – is how unprofessional the industry was, with health and safety checks at a minimum and no union in place until years later.

“We used to sign these things called a bloodshed, which is basically a certificate, you know, absolving the company from any responsibility of whatever happened to you whether a lamp fell on your head, or whether, you know, they blew you to pieces,” says Jim. “It was a lot cruder. In that lovely sequence from You Only Live Twice with everybody coming down through the roof, I saw that and thought, ‘Jesus, if one of those guys gets it wrong, he’s just gonna keep going and go through the floor.'”

Was there any appeal to that risk?

“I don’t mean to glamourise some aspect of us all being pirates. It was a much smaller fraternity in those days. You knew other people’s skills and you knew who you could go to. Now we’ve got 465 members of the British Stunt Register. In those days, where about 60 or 70 of us.”

That sense of camaraderie is captured by Jon Spira’s documentary, with each stunt person clearly trusting and respecting each other’s abilities.

“There is a bond between us because we’ve all been in situations where we’ve looked after the other person’s safety,” Jim observes.

“We had a lot of fun,” he adds. “In those days on set, when you were on a Bond movie, it was like a family, we’d all get together every 18 months or two years and do another film and everybody knew each other. People who work on them today tell me that it’s very different. We used to fuck about on the Bonds, but as long as you pulled it out of the hat when the camera was rolling, that was what mattered. There was a joy in the filmmaking we did.”

While Vic Armstrong went on to double Harrison Ford in the Indy franchise, Dowdall leant more into co-ordinating stunts.

“Vic and I came into the business more or less at the same time,” recalls Jim. “He was always a much better performer than I ever was, because I didn’t have some of the skills that he did.”

But Dowdall’s knack for working out how to do things safely has been with him since his very first gig at the age of 18.

“I got a call to go down to Twickenham Studios and do a live ammunition job with real bullets. I’m 18 years old, I’m a rocker. I’ve got black leather jacket with studs, and long greasy hair. And I strap these guns on the back of my motorcycle, I don’t know what the film is, I’m too busy being a rocker. And I’m taken on to the set, which is the interior of a castle, about the 1900s. And there’s a painting on the wall of a woman and they said to me, ‘Well, we want to shoot holes in that.’ So I spent the morning with it and we made a bullet-catcher behind with sandbags and bits. At lunchtime, I’m told, ‘Right, we’re going to meet Mr Lawrence Olivier.’ So I’m wheeled into the great man’s dressing room. And he gets up and he comes over and he shakes hands. And he says, ‘Hello, my name is Laurence Olivier, thank you so much for coming.’ This is , you know, arguably one of the greatest actors of his time. And he says, ‘We intend to do this shot as a separate shot at the end of the day, but do you think there is any way that we can do this in one take? Now?'”

“I was cocky,” laughs Jim. “I said, ‘Yes, sir. I think if I stand on a stepladder, just behind the camera, and you take the revolver and you turn your back to the camera. Now you can cue me, as you fire a blank, I’ll fire over your left shoulder.’ He said, ‘Do you think that’s safe?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, it’s fine. You just need to put some wax in your left ear, because it’ll be a bit of a bang.'”

That early experience taught Jim not only about being careful but also about the importance of teamwork, with everyone on set listening to each other and taking into account everyone’s experiences.

“There have been some unnecessary injuries in our business,” he notes, “which are caused through a mixture of ego and ignorance.”

The focus, though, is realising what the director’s vision is. For Jim, that’s ranged not only from serious action to comedies such as Mindhorn. How much does the nature of the work change when working on a set piece that needs to be funny?

“You have to think, ‘Are we looking at slapstick here?’, which can actually be more dangerous,” he explains. “For slapstick you need a spontaneity that’s going to surprise the audience. So rather than telegraphing something slightly ahead, as you might do in a normal fight sequence, when you’re doing comedy, you’ve got to try and rehearse something, but not over-rehearse it. If you get a crew laughing, you’re on the right track.”

Co-ordinating things effectively but also safely is what gives Jim the greatest satisfaction.

“If a director comes to me at the end of the shoot and goes, ‘Thank you, we really, you know, we appreciate your input’, that’s all I require. I’ve been co-ordinating since the 70s and I like to think that I haven’t hurt anybody with my performance or with actors. I try and make things possibly too safe, because I’ve worked with co-ordinators in the past where I’ve been the performer and I’ve been the monkey on the stick, where they don’t care about you. I’ve finished up in the hospital getting some stitches, and whatever, and that’s fine, but you learn from the mistakes. I got bitten on on Dad’s Army, and I got hurt quite badly. Because I pointed out what the way that we should have been doing it in my eyes. And the co-ordinator said no. I like to listen to my stunt performers, because there are things that they’re going to see in the rehearsal, and they’re going to come to me and say something. I’ve tried never to be egotistical.”

In the age of CGI, there’s something about stunt performers that could be considered old-fashioned, but Jim highlights the tangible value to practical effects and spectacle that hasn’t gone away.

“You can buy extraordinary CGI packages to use on your Mac at home and there are kids who are 12 and 14 that can do now what visual effects people were doing 20 years ago. They just go diddily diddily dee and suddenly this car explodes. But audiences are also taking far more interest about how the stunts are done when it’s done in camera, not in a computer. And we’re going back to a realisation that there is still a texture that CGI cannot reproduce. There is a texture about it, where your eyes see people doing it for real. And that’s valued, I believe, by the audience.”

Decades ago, films were the end goal for a stunt performer or co-ordinator, as they led to longer contracts and higher pay. Today, though, the industry is also changing in the way that TV has become more cinematic.

“The element of spectacle is reducing down to this small screen,” agrees Jim. “But if you look at The Night Manager and shows like that, with the quality of the script and the acting and the action combined together, you wouldn’t be able to delineate that between cinema and TV.”

As for Jim, he still does the “odd little car crash” and other work “just to keep my hand in”. His most recent credit is Tenet.

“I was just precision-driving some cars,” he says. “George Cottle was the stunt co-ordinator and does all Christopher Nolan’s films. I gave Georgie one of his first jobs in the industry. And he’s a very, very bright boy, an absolute credit to us. He just said, ‘I’d like you to come in and do a little bit on it.’ So there was nothing dangerous, daring or anything else, it was a question of being able to drive and arrive absolutely on the mark, with people passing in front and cameras and that kind of stuff. Precision-driving is one of the things that I’ve specialised in, I’ve done nearly 300 car commercials. I’ve jumped over things, I’ve driven along the tops of buses, I’ve driven up the inside of lighthouse…”

But even now, Jim is still in love with the process of film-making.

“It’s very interesting watching how Christopher worked, because he’s clearly a man who’s very focused. He knows what he’s doing, but he’s working off the wrist, rather than working to a set storyboard. On Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, I played a villain in a fez with a moustache and we’re doing this speedboat chase. When we arrived on the set, there was a big board there with every single frame, with the lens size and everything else, because Spielberg has done an animatic and essentially cut the entire film together. And all we’re doing is film this storyboard. It was very clinical. 15 years later, we’re doing Saving Private Ryan and suddenly Spielberg’s got four camera crews and he’s doing things where his experience has completely changed his modus operandi and making movies. I would love to ask him about that. I just like film history, you know?”

Hollywood Bulldogs is available on BritBox, as part of a £5.99 monthly subscription.