The election’s the thing: How House of Cards Season 4 got its Shakespearean groove back

David Farnor | On 03, Mar 2016

This contains spoilers for Seasons 1 to 3 of House of Cards.

“I thought you hated politics,” says one analyst to another halfway through Season 4 of House of Cards. “I do, but anger and seduction? Those are interesting.” It’s the kind of conversation you can imagine two punters having while debating whether to see a historical play – and Netflix’s show, which has always owed a debt to The Bard, is firmly back in Shakespeare territory.

Richard III was the initial touchstone for Frank Underwood’s rise to power, as Kevin Spacey’s unctuous politician worked his way up the corridors of power, talking to us as he slithered. Spacey revelled in the role with an uncanny ability to charm an audience – and he was perfectly matched by Robin Wright as Claire Underwood, Frank’s statuesque wife with even less of a conscience than her husband. As the show unfolded, though, that to-the-camera style faded. Psychological drama turned to soap opera hysterics. We jumped from the corridors of power to the bedroom of power, as House of Cards focused on the fallout of Frank’s actions upon his and Claire’s marriage.

Season 4, though, is something of a return to form, as the couple’s personal conflicts become political once more – their disagreements are dragged back out of the bedroom and onto the campaign trail.

In the real US election, of course, there’s already a scary male figure attempting to hoover up all the attention: Donald Trump. Where showrunner Beau Willimon might have conjured up an equivalent figure to mock, the writer chooses to stick to House of Cards’ more timeless approach of context-free archetypes. Topicality still looms. Gas prices remain an issue. Russia’s leader (Lars Mikkelsen) is back for more sleazy negotiation. Corbyn-esque rival Heather Dunbar (Elizabeth Marvel) rides a wave of moral outrage that could have started on Twitter. A brush with the Ku Klux Klan, something that has troubled Trump in recent weeks, also haunts Frank, while the events of Ferguson can be felt in the introduction of Doris Jones (an amazing Cecily Tyson), a Texan congresswoman with whom Frank and Claire must make peace.

“I’m appealing to your goodwill,” Frank tells her, during one heated conversation. “When we stop getting beaten and shot, you’ll have my goodwill, Mr. President,” comes the reply.

The focus, though, is more and more upon the past.

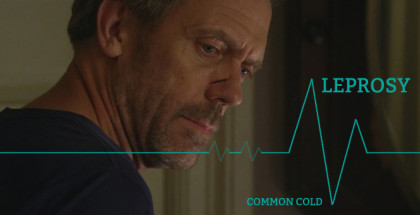

Underwood’s betrayals and bumping-offs become ever more pertinent here, in an election race where things start to stack against him – even now, years after Zoe Barnes and Peter Russo, their deaths are waiting to spring out at our protagonist with an unexpected bang.

It’s that feeling of raised stakes that gives Season 4 its weight, but also relocates us at a different point in Richard III’s narrative: the final acts, where the king’s downfall begins. The friendly banter with the audience dries up, replaced by rebellions, paranoia and genuinely creepy nightmares.

“They’ve already lost the election, they just don’t know it yet,” argues one analyst during a pessimistic chat. It’s the kind of ominous declaration you could almost imagine Underwood dreaming. Certainly, the visual style of the show has changed, as we’re dragged into the darkening recesses of Underwood’s struggling mind. Even the introduction of Claire’s mother, Elizabeth (a gloriously ruthless Ellen Burstyn, every bit as calculating as her daughter), has a ghostly feel, as we see her walk through her eerily empty family estate.

Within the first six episodes of Season 4 made available in advance to the press, the smell of blood in the air is strong, as everyone from our lead couple to Doug Stamper burst into moments of violence. That growing air of doom, mixed with an almost supernatural sense of past sins haunting the present, pushes us further and further away from Frank; a detachment that’s emphasised by both increased screentime for the supporting cast (including the Vice President) and, yes, those now-rare asides. After three seasons of moral disgust, though, that distance is actually satisfying. For the first time, we begin to wonder what the show could be like without its lead character. Could we finally be about to witness his comeuppance? And what would that mean for Season 5, which has already been announced?

Showrunner Beau Willimon is in his element here, his ballot box dispatches recapturing the cynical glint that made The Ides of March (and House of Cards’ opening season) so gripping. That’s partly because he seems to have rediscovered his inner Richard III, but also because this is an election year – and House of Cards feels at its best in an election year. This is a time when primaries and caucuses are words that trip off everyone’s tongues, not just those in the industry, when debates and double-crosses genuinely impact how people vote, when all the contrivances that would otherwise seem absurd on screen pale in comparison to the bizarre election drama of real life. It’s a theatre of artifice and mistrust, which allows House of Cards to play its most brazen cards without anyone blinking. Blood drips from taps. Mirrors shatter. You might be able to picture the whole thing without Frank, but it’s hard to imagine it without Willimon, who will depart the head writing chair at the end of this run. In his hands, House of Cards isn’t just politics: it’s anger and seduction, high themes presented to the public through low thrills. It’s hard to think of anything more Shakespearean.

All episodes of House of Cards Season 4 arrive on Netflix UK on Friday 4th March. Come back then for additional spoilers for Episode 1 – and stay tuned for our reviews of each episode, as the season unfolds.

Photo: David Giesbrecht/Netflix