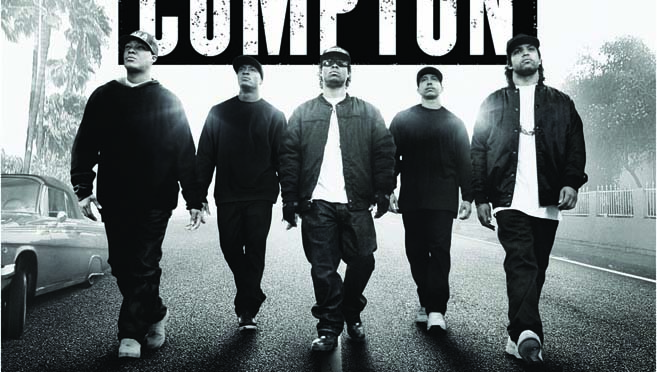

VOD film review: Straight Outta Compton

Review Overview

Performances

9Tightness

6Josh Slater-Williams | On 19, Jan 2016

Director: F. Gary Gray

Cast: O’Shea Jackson Jr., Corey Hawkins, Jason Mitchell, Paul Giamatti

Certificate: 15

The problem with most biographical dramas, particularly those concerning musicians, is that they can often play like greatest hits samplers rather than a cohesive, insightful character study. Some of the best music biopics are those that take a formally interesting approach that feels akin to the spirit of the artist/s in question, rather than trying to box their persona into a rigid formula; Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There is one example, as is the recent Love & Mercy, which offers a dual performance to depict two decades in the life of subject Brian Wilson, but also sonically innovative soundscapes to convey the troubled genius’ artistic process.

This is not to say that the traditional music biopic formula is of inherently dubious quality. As with any genre, execution is key. Straight Outta Compton, a portrait of N.W.A. (though mainly members Ice Cube, Dr. Dre and Eazy-E) from director F. Gary Gray, is one such example of the formula done very well. Or, at least, up to a point.

For the most part, Straight Outta Compton is an often exhilarating snapshot of late-80s America that relies on a rhythmic flow just as much as the songs at its forefront. When it comes to conveying the creation and meaning of those songs, it succeeds where so many music films fail in getting across the power and essence of the art; art, not just hits. There’s urgency, catharsis, an actual engagement with the social and political aspects of the music, and three greatly charismatic lead turns at its centre. O’Shea Jackson Jr. (a dead ringer for father Ice Cube) and Corey Hawkins as Dre are both great, but the film’s standout is the electrifying Jason Mitchell as Eazy-E. Fellow N.W.A. members MC Ren (Aldis Hodge) and DJ Yella (Neil Brown Jr.) are sadly given the short shrift in terms of screen-time or, really, any notable character arcs, but then that is possibly a side effect of Cube and Dre being major creative forces behind the scenes of this film. One might say that Hodge and Brown Jr. aren’t given any beats by Dre to play.

For about 90 minutes, this is a classically told, well-crafted take on a musical form still marginalised when it comes to large-scale, mainstream depiction on the big screen. Unfortunately, the film still has another hour to go after this. And go on and on it does. Where the film’s earlier sections thrive on honing in on a specific creative period (though acknowledging the rapid nature of the actual events and sudden success), the latter ones are preoccupied with skimming glimpses of a lot of notorious events that the screenwriters seemingly thought had to be in the movie solely because of their notoriety. So we get a lot of violent encounters involving Suge Knight. We get “hey, look” appearances by Snoop Dogg and Tupac. We get references to the making of Friday, which F. Gary Gray happened to direct.

There’s not a lot of outright bad material in Compton’s final hour, but too much of it feels like infamous incidents rather than necessary parts of the story. What begins as a vital reflection of its three principal players’ place within the American cultural landscape descends into a self-serving, protracted wallow in the muck of endless contract disputes; the fiery drive of the first half gives way to what’s effectively an aimless, extended epilogue, culminating in an end credits highlight reel of all the stuff Cube and Dre have done since. One might be a little more forgiving if they’d got Jackson Jr. to re-enact Cube’s buffet table breakdown in 22 Jump Street.