The eyes have it: Looking back at the timeless memories of Blade Runner

Review Overview

Humans

10Machines

10Eyes

10David Farnor | On 30, Sep 2017

Director: Ridley Scott

Cast: Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young

Certificate: 15

Warning: This contains spoilers. For more on where to watch Blade Runner online without reading spoilers, click here.

“If only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes…”

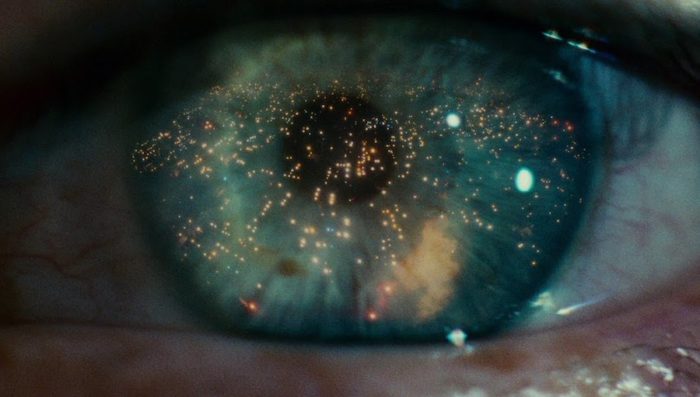

From the very beginning, Blade Runner is obsessed with eyes. Ridley Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece, which remains timeless 35 years on, begins with a startling vision of the future steeped in the past: a cityscape of Los Angeles in 2019, a place of pyrotechnics and pollution. And immediately, we see that city reflected in the eye of Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), a gazing, blue iris shot through with glistening flames. Roy is one of several rogue Nexus 6 replicants, androids so advanced that they’re almost impossible to detect – apart from through the Voight-Kampff test. The thing it detects? Eyes. Or, specifically, involuntary dilations of the pupil, which only occur in humans, as they react emotionally to certain scenarios. When it comes to telling the difference between man and machine, determining the presence of a soul, the eyes have it.

That motif extends throughout the film, which, fittingly, is visually jaw-dropping. Scott’s direction, in conjunction with Jordan Cronenweth’s cinematography, Doug Trumbull’s effects and Lawrence G. Paull’s production design, still looks as beautiful as ever, combining the down-to-earth grime of the LA streets with the neon signs that float above it. Somewhere between Raymond Chandler and Edward Hopper, it’s a universe that consists of silhouettes and scummy pavements, loneliness hard-boiled into every figure. Accompanied by Vangelis’ haunting score, which fuses new-age synths with romantic 1940s saxes, it’s less noir-tinged and more noir-tainted. We never really see daytime throughout the movie’s runtime: with a large chunk of the population having fled Earth, we see it as a place of perpetual rain and endless nighttime. No wonder the fixation on eyesight.

For Roy, his hunt for the person who made him begins with his ocular organs: he visits Hannibal Chew (James Wong), the scientist who designed them, and it’s during his interrogation of the geneticist that he serves up his first of many delicious lines of dialogue: “If only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes…”

Rutger Hauer is iconic in the role, delivering the script with a knowing glint in his eyes – one that can give way without notice to an ice-cold stare. That’s most apparent in one of the most famous lines in the film, a poignant soliloquy uttered just before his demise at the end.

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,” he begins, before rattling off dazzling images of far-flung miracles that we never get to see. Hauer wrote half of the speech himself, the night before it was filmed, choosing to replace Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples’ screenplay with something he saw as more natural.

Perception, here, is everything, and what’s so remarkable about Blade Runner’s profound, philosophical worldview is that it’s born of people viewing things entirely differently.

The movie’s based on Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, a novel about a man, Rick Deckard, whose job is to hunt down the rogue Nexus 6 androids and kill them (a “blade runner”). In the text, we spend a lot of time in his day-to-day, post-nuclear-war existence, where humans live in abandoned apartment blocks trying to rediscover their sense of connection with each other. There’s a whole religious cult built around it, Mercerism, powered by tiny networked boxes.

The film jettisons a lot of that to focus on the more action-driven detective story, but the fusion of empathy and technology is still central to the whole story. Harrison Ford’s take on Deckard is a marvellous portrait of restraint and dispassion: he’s a cool, methodical bounty hunter with a determined edge that means he can get his grisly job done. Even as he falls for Rachael (Sean Young), the icy receptionist working at the Tyrell Corporation (who created the Nexus 6 models), their love scenes are harsh and mean, more bullying than compassionate.

Harrison and Hauer are the epitome of binary opposites: as Harrison becomes more and more a killing machine (even relying on computers to study photographic evidence in detail), Hauer becomes more and more animated; Rick doesn’t smile or laugh, but Roy is forever grinning; Deckard’s speech is terse and blunt, but Batty’s final dispatch is now regarded as pure poetry.

It’s that juxtaposition that sparks the movie’s biggest question: is Deckard a replicant or not? An origami unicorn and a dream sequence featuring one hints at the bleak answer, but the film never comes down on either side of the argument. Why? Because nobody making the film saw eye-to-eye. The suggestion that he might be a machine only came about because Fancher and Peoples had crossed wires when exchanging drafts of the script. Scott, as he has said since, is convinced Deckard is an android, but Ford is certain that his gumshoe cop’s not a computer. The distinction is made even muddier by studio interference, which initially removed the unicorn dream sequence (and the implication that such visions had been implanted in Deckard’s head) and added a happy ending with a cheesy voiceover that was so forced Ford ironically did sound like a robot recording it. (Note: The version of Blade Runner on Sky Cinema and NOW is this 1982 theatrical cut – we recommend hitting pause at 1:47:51.)

In total, there are now seven versions of the film, with the 2007 Final Cut arguably the definitive one (this and the theatrical version are the cuts available to buy and rent online, except for TalkTalk TV Store, which has the director’s cut). Yet curiously, Dick’s novel isn’t even about the Deckard question: after writing The Man in the High Castle, he was partly inspired by Nazi diaries to explore the deliberate dehumanisation of enemies perceived as alien and inferior, in a collapsing, morally corrupt civilisation. In Scott’s hands, that story becomes one that was perhaps meant to feel closer to home, as he crafts a world where commerce and capitalism rule over a melting pot of cultures – The Crystal Maze’s Industrial Zone writ large, in which people are reduced to consumers, and, in the case of synthetics, literal products. But there’s still an element of moral horror that remains, as Batty and Deckard’s climactic confrontation (made longer, more visceral and violent for the screen) results in Batty saving Deckard’s life – in a brightly-lit shot, complete with dove flying towards the heavens, this purportedly inferior saviour expires as the better man.

Humans, certainly, don’t come across very well: all of their female androids are largely male fantasies, from the flexible pleasure robot Pris (Daryl Hannah) to Zhora (Joanna Cassidy), a snake-wielding erotic dancer, gunned down in a see-through raincoat in slow-motion amid the strip joints and cheap noodle bars. When they do make something in their own image, they treat them as a force for labour. “Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it?” says Batty, at the finale. “That’s what it is to be a slave.” With the Tyrell Corporation’s headquarters towering over the city as an extravagant pyramid, humankind has taken great technological leaps forwards, but has made no real progress at all (see also: Channel 4’s Humans).

Talking to Dr. Tyrell (Joe Turkel), who wears gigantic glasses that mask his eyes, Deckard quizzes him about the way they created the more advanced models more stable and humanlike: by giving them false fragments of childhood details, a cushion for their mind to fall back on. “Memories,” muses Deckard. “You’re talking about memories.” When Batty comes to deliver his famous speech, that’s exactly what we get.

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,” he intones. “Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

What’s so bewitching about these memories is they’re real: actual memories that Roy has forged himself as a slave working off-world, memories that the authentic, original humans stuck on the rain-soaked Earth will never see.

Whether you see Roy as the hero or not, there’s an unspoken truth in Batty’s quest to meet his maker: he’s racing to beat an expiry date that was installed in him from the beginning. Why have that four-year deadline at all? It’s not because the androids are sub-human, but because they’re becoming super-human, as they develop raw emotions and even empathy, based on their new experiences. The Tyrell slogan is “more human than human”, and that’s precisely what the humans live in quiet fear of: that this species it has fashioned is not just similar, but even better.

No wonder the film’s only swear word comes when Roy does confront Tyrell: “I want more life, fucker,” he demands. And then, he kills his father, by gouging out his eyes. Sight plays heavily upon the consciousness of these beings, who have repeatedly had no option but to see things that humans wouldn’t believe. Extinguishing the windows to another person’s soul becomes as final a gesture as it gets.

But if there’s an oedipus techs tragedy at the centre of Blade Runner, there’s hope, too, in the signs of compassion that we glimpse. It’s too bad these people, man or machine, won’t live forever, but affection is pretty good, even between a man and a toaster (in the words of Harrison Ford), regret is tangible, as Roy mourns Pris’ death, and, as Deckard and Batty face one another, empathy is essential.

The result is a gorgeous, melancholic study of morality and memory, one that appears as fresh now as it did in 1982, thanks to its pitch-perfect cast, astonishing world-building and, most of all, the endless ways to view its main protagonist. Lost in time? Not a chance. Part of cinema’s magic is how it acts like memory, the camera lens able to see all these moments through its characters’ eyes and save them for the future. In its own way, Blade Runner remembers humanity – and, like all great movie masterpieces, helps to define it. All you have to do is look.