Netflix UK review: Black Mirror: Bandersnatch

Review Overview

Cast

9Direction

9Decisions

9David Farnor | On 28, Dec 2018

Warning: This contains mild spoilers for Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Already seen it? You can read our guide to all the available endings here.

“What have you done?” “Chose for you. You OK with that?” “Yeah.” That’s Stefan (Fionn Whitehead) in Bandersnatch, Black Mirror’s first ever film – and, more to the point, its first ever interactive film. Yes, just when you think Charlie Brooker can’t disturb you anymore with his dystopian tech anthology, he’s point-and-clicked into another element of existence to unsettle your brainwaves – namely, free will, or the illusion of it.

There’s something wonderfully fitting about Black Mirror embracing the choose-your-adventure format for a one-off special: it’s a show that delights in placing us in the most awkward, disturbing position possible, and, normally, relishes leaving us passive and unable to halt what’s happening. It’s wince-inducing, anxiety-ridden television at its best. Bandersnatch, though, lets you meddle where you dare – and, just to top it off, also leaves you questioning whether your meddling makes any difference whatsoever.

If that sounds enjoyably meta, hold onto your joystick: we’re only at the first tree branch. The plot follows Whitehead’s 21-year-old programmer, who, in July 1984, has a meeting with a games company to pitch his idea: an adaptation of Bandersnatch, a novel he’s loved since he was a kid. A choose-your-own epic by Jerome F. Davies (no, he’s not real – but a nearly-released game called Bandersnatch is), it’s a fantasy saga that sees the reader grapple with Pax the demon. The book, though, caused Davies to lose his grip on reality, as he began to meditate on the nature of choice and fate, reaching a brutally paranoid conclusion. It’s no surprise to say that Stefan does the same.

That self-aware streak runs all the way through every frame of Brooker’s winding, teasing labyrinth, which nods to Black Mirror’s past – look out for a poster for METL HEDD, a reference to Metal Head, the black-and-white episode that David Slade also directed – and even briefly refers to the concept of Netflix at one point. With Stefan’s end result aiming to be a computer game played by many and reviewed on national TV, there are endless opportunities for your decisions to impact the final outcome of his efforts, and how it might or might not be received.

Or are there?

The film is stuffed with tiny, everyday choices, such as what cereal to have for breakfast, each one raising the unknown appeal of taking the other route – a conscious line between differing realities that perfectly matches the parallel-universe thinking that Stefan finds himself grappling with. And it’s here that Brooker’s handling of the format is so breathtakingly witty and elegant; he deconstructs the idea of a choose-your-own tale with humour and horror, but also rebuilds it into something more surprising, shocking and moving. An initial flashback to a poignant back-story doesn’t appear to give us the option to change events, locking in a trauma that Stefan, like us, can’t avoid or escape.

So when we do have the chance to make decisions, we’re all the more eager – even though each one of those sends our hero further into a spiral of despair, as he begins to question whether someone else (yes, that’s us) is actually making all of his life decisions for him. It’s a remarkably prescient bit of social horror: in 2018, who hasn’t, at some point, felt the fear of not having any control over the events happening around us?

Characters throughout talk about choice and lack of it, almost winking at the proverbial camera, just to really send your mind spinning. Best of all is the fact that, while Netflix’s 10-second rewind button is present and correct, you can’t go rewind to before the last selection you made – once you dive down a rabbit hole, you have to dig your way back out.

The presentation itself is as slick as the more family-friendly choose-your-own specials Netflix has previously released for kids (see Puss in Boots and, more impressively, Buddy Thunderstruck); you’re given a 10-second window for a binary call, or Netflix will decide for you and keep going. In a masterclass of editing, the scene will continue to run past that deadline before cutting to your answer, making the whole thing genuinely seamless.

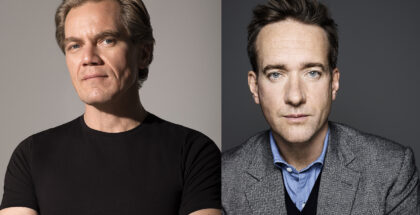

A major part of making that possible is the cast, with each actor having to perform scenes not just with different dialogue, but in different tones and with different emotional responses. Whitehead is great as Stefan, who moves from quietly pondering metaphysics to giddily staring at his computer screen with a manic terror, but he’s got some superb support that make it all feel realistic. People Just Do Nothing’s Asim Chaudhry sinks his teeth into the chance to explore a more dramatic role (watch out for him in Ben Wheatley’s Happy New Year, Colin Burstead) as gaming boss Mohan Tucker, who cares more about profit than people. Will Poulter is also excellent as Colin Whitman, a computer whiz whose own creative process opens windows into the tumbling mental process of assembling (or dis-assembling) an entire world. He delivers drug-addled tirades about free will, about PAC Man being a prisoner in a maze with no agency, but laces those lectures with government conspiracy theories and other gibberish – Slade frames him in garish colours, his blank, reserved features coming to wide-eyed life, to the point where we don’t know whether to buy into his philosophy or laugh it off.

His idea that it’s irrelevant what choices you make, though, because other timelines exist regardless (in which you live, die, have a different bowl of cereal, and so on) does linger in your head – and, as Brooker ramps up the stakes of what’s in play, Black Mirror begins to challenge us with the question of how far we’d go, if we thought that, in the long run, even the most heinous crime would be rendered negligible by time and space. Alice Lowe adds to that intense air as Stefan’s therapist, Dr. Haynes, while also allowing for a vulnerability that’s anchored around Craig Parkinson’s tender performance as Stefan’s dad.

But, and this is something of a relief when Black Mirror could have taken the predictable route of one unavoidable destiny, there are multiple endings to Bandersnatch. (In our play-throughs, we found around four different endings, with various ways of reaching each one.) There is, for example, the option to take things in a darkly comedic direction. (If you end up in a timeline in which one character has to choose whether to kick another, you’ve officially won at Black Mirror, as Brooker seizes an opportunity to go completely unhinged.) There are also amusing references to alternate fates, as one character thanks you for sparing them an ordeal. It all adds a breath of novelty to a series that could easily have become stale by now – after Season 3 and 4 shockingly ventured towards (gasp) the occasionally happy ending, the pressure was on for Black Mirror to find a new way to entertain us.

And yet, inevitably, there are parts of Bandersnatch that we can’t quite steer away from. Navigate too forcefully down a path and you’ll find yourself with an abrupt ending that acknowledges how short it is – or try to avoid a key piece of exposition and you’ll be gently nudged towards it. There’s also a key emotional sequence that keeps cropping up, even when you delay it – and while that’s essential from a storytelling perspective, the peppering of fixed and flexible beats in a random order and at an unpredictable pace leaves you wonderfully on the edge of your seat as to which type you’ve just encountered. By the time you get to the ending you’ve caused, you’ll immediately want to go back and experiment with another one. It’s a testament to how well executed Bandersnatch is that Black Mirror has already anticipated that too – because who needs free will anyway?

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch is available on Netflix UK, as part of an £9.99 monthly subscription.