VOD film review: 12 Angry Men

Review Overview

In front of the camera

10Behind the camera

10Idealism

10David Farnor | On 30, Aug 2015

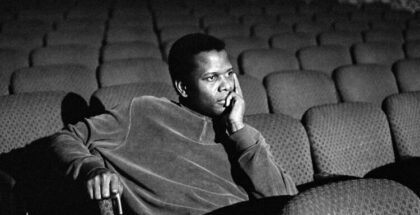

In the world of cinema, one man cannot make a masterpiece. Even Sidney Lumet, a film-maker spoken of in the kind of revered tones used for that most loved of modern auteurs Christopher Nolan, had a team of people around him to make something as outwardly simple as 12 Angry Men.

The story needs no introduction – a jury deliberate the fate of one young suspect in a murder trial, with a single member of the group arguing the “Not Guilty” case – but the rest of the film makes it worth revisiting, almost 60 years after it was made. With 12 actors at the top of their game in front of the camera, it’s easy to overlook the sublime work happening elsewhere, from the lighting and camerawork to the precise positioning of the smallest object. “There’s always one…” sneers Ed Begley’s Juror #10, when Juror #8 – Henry Fonda (who else?) – counters the “Guilty” consensus. But in fact, there’s a multitude of people creating that iconic moment: everyone in front of the camera and behind it is working their black-and-white socks off.

The colour scheme is the most notable, and perhaps most discussed, aspect of the production, as Fonda’s lone crusader for justice wears a white suit in a room full of darker jackets: he jumps out of the screen visually, as well as verbally, his calm, charismatic approach carrying the kind of confidence needed for a brightly-coloured suit. As the jurors, one by one, come over to his way of thinking, the rest of the cast sell their individual traits far beyond the basic stock types they could have been, from the elderly Juror #9, whose age brings him wisdom and – in Joseph Sweeney’s hands – a likeable, fragile way of expressing it, to the young, careless Juror #7, who is more concerned with the baseball game taking place that evening, an attitude given a blasé delivery by Jack Warden. He even wears a hat.

What’s most impressive, though, is the way they move about the set. Deviations from the group’s thinking, or solo musings aloud, are accompanied by individuals rising from the table and pacing the room: those in the defendant’s corner are literally standing up for him. During the heated climax, Juror #10’s racist rant – “You all know he’s guilty. He’s got to burn. You’re letting him slip through our fingers.” – sees the rest of the room turn their backs on him, leaving him speaking to a brick wall. With the electric fan near the door broken, the group even start to take off their jackets, the whiteness of their shirts echoing Fonda’s outfit.

Lumet came to the big screen from theatre and TV, a background that would have left him both familiar and trained in the art of blocking, especially within confined spaces: along with a fondness for rehearsing in depth with his cast, the result is a finely honed piece of choreography, where each gesture adds to the shifting dynamic of the room. The tension between these conflicting views isn’t just in the air; it’s

there for all to see.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the screenplay was penned by Reginald Rose, a writer who had (and went on to have) extensive experience in television. That small-screen background certainly left some critics taking against the director during his early cinematic career, but there is visual flair on display even in this most basic of set-ups. The single-room premise may reek of a low-budget TV special, but Lumet knew how to use that to his advantage: he begins with a bravura opening shot that tracks through the whole place, introducing each actor in turn, a feat of planning and execution that is even more effective given the space available. He goes on to shoot the action from high up in the room but, as the film progresses, the camera gradually lowers, taking us down to the level of these increasingly petty men. By the end, the ceiling has started to loom at the top of the frame, which, combined with a knack for long takes (contrasted with short cuts to dramatic close-ups), emphasises the claustrophobia of the whole thing. Even the light changes from sunny daytime to a stormy night – the pathetic fallacy is hardly subtle, but the symbolic weather means that Fonda’s suit stands out even more in the darker room, while the sense of freedom and fresh air when the men finally walk out of the courtroom is palpable.

Not bad for a director making his first feature. But 12 Angry Men also marks the start of not just Sidney’s technical prowess, used in service of the script in hand, but a thematic preoccupation: it was the start of a parade of angry men to be caught on Lumet’s camera, from Network’s mad-as-hell-and-not-going-take-this-anymore Howard Beale to Al Pacino in Dog Day Afternoon and, in 2007, the desperate brothers of Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. While not always present, his tales often seem to include an individual railing against the corruption in (usually New York’s) society – a soft spot for anti-conformity that’s hard not to sympathise with.

In the current world, 12 Angry Men’s moralising is just another quality that marks it out as a classic – it’s hard to imagine something with so much optimism being written today, let alone being released. Indeed, Before the Devil, which came a staggering 50 years later, sees even Lumet succumb to the more cynical modern worldview, with his jewellery-robbing duo (Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman) facing the consequences of their cruel actions. “The world is an evil place,” it teaches us. “Some people make money from it, some people are destroyed by it.” The fast-cutting, non-linear approach makes 12 Angry Men seem idealistic by comparison.

There is a sly ambiguity, though, to the juror’s heated discussions. They are full of modal verbs and their substitutes, all conveying a sense of uncertainty and a lack of knowledge. “Maybe” this. “Suppose” that. “You can suppose anything,” observes one. Henry Fonda’s governing principle, meanwhile, isn’t that the defendant (who, in another Lumet tradition, is an outsider – in this case, an unspecified ethnic minority) is innocent, but that he might not be guilty.

Written at a time when cinema was helping to shape a country’s perception of itself – the presentation of “America” vs America – there is an old-fashioned hope to the notion that a stranger can defend another’s right to be presumed innocent. If that makes 12 Angry Men corny by contemporary standards, it only makes the work more admirable in its unabashed sentimentality. One man’s voice can make a difference, Lumet reminds us, but he can’t do that alone. It’s a group statement from an accomplished team; a unanimous masterpiece.