Why Britain believes in Rev

David Farnor | On 03, May 2014

Last month, UK Prime Minister David Cameron said that he believed “we should be more confident about our status as a Christian country”. The comments, written in The Church Times ahead of Easter Sunday, prompted 50 notable public figures to write a letter in response, saying that Britain is not a Christian country, that many polls showed most individuals are not Christian in belief or religious identity. “Constantly to claim otherwise fosters alienation and division”, it added.

Why, then, is Rev, a sitcom about a vicar in the Church of England, so popular?

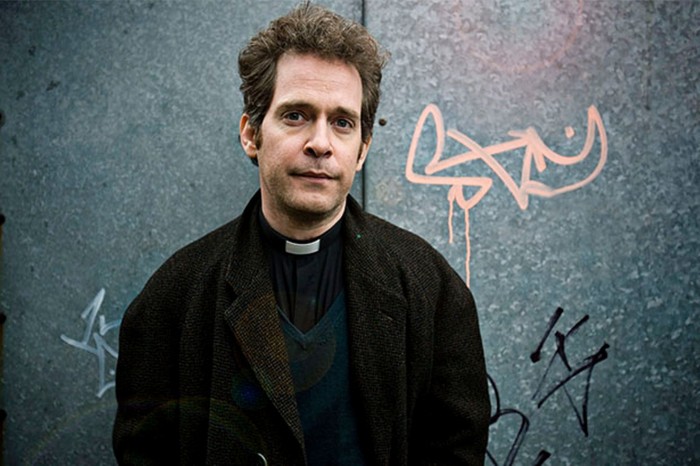

The secret largely lies in its star and creator, Tom Hollander. The actor has described himself in interviews as an atheist but grew up as a choirboy, an upbringing that stuck with him – and inspired him, following a friend’s christening, to write the show with James Woods.

The result was a series that highlights the individual over the institution; a story about a man struggling with faith in the face of modern, urban life, while dealing with issues ranging from gay marriage to hypocritical parents using the church to get into local schools. He smokes. He drinks. He’s friends with a drug addict (Colin – played by Steve Evetts). The Vicar of Dibley, it ain’t. It was a hit, winning a South Bank Award for Best Comedy in 2011 as well as a BAFTA for Best Sitcom.

Three years on, and Reverend Adam Smallbone (Tom Hollander) is still trying to keep St. Saviour’s in East London open. His congregation is shrinking, the coffers are empty and the church seniors are running out of patience – much to the annoyance of uptight lay reader Nigel (Miles Jupp) and the amusement of social-climber Archdeacon Robert (a delightfully snide Simon McBurney).

Sound bleak? That’s because it is. And that’s a good thing. Rev’s strength has always been in its ability to take the serious with the silly: more sit than com, it’s drama first, entertainment second. The supporting cast (from Jupp to Evetts) occasionally slip into stereotypes but Holland himself (and Adam’s wife, Alex, played by the perfect Olivia Colman) feel absolutely genuine.

A crucial part of that is the programme’s treatment of Adam’s faith. Jokes are inspired by it, not made at its expense.

Adam pray, for example, at any time of the day about trivial things as well as serious – a voiceover that Holland delivers timidly, with the odd swear word thrown in. It’s precisely the kind of device that shouldn’t work but that Rev pulls off easily.

Season 3’s Easter episode sees Rev suspended due to accusations of a fling with local headteacher Ellie, whom he desperately fancies. Penitent and wasted, he stumbles home to his pitying wife, only to remember he has to deliver a crucifix to a nearby church. He stumbles through the capital’s streets shouldering the burden of a cross – a literal metaphor that could’ve have been heavy-handed, but because we like Adam, we accept it, right down to the symbolic washing of the hands by his Deacon (Ralph Fiennes). The morning after, Rev wakes up on a hill, only to be greeted by a glowing Liam Neeson. “I saw God” he splutters at Alex. She looks bemused.

Even those who aren’t religious swallow these moments. Their reverent irreverence make them engagingly sincere, which means that when we’re not laughing, we’re caring. There are criticisms of the church in there – Adam’s services are attended by weirdos and drunkards and he’s frustrated at not being allowed to perform gay marriage – but these are presented not as scathing satire but rather as natural extensions of Adam’s own failures; everything and everyone is flawed.

The show’s ongoing consultation with the church (Richard Coles of St. Paul’s, Knightsbridge, Andrew Wickens of St. Botolph’s, Boston Stump are both credited as consultants, while they’ve also held roundtables with vicars) suggests that it might be somehow pro-establishment, while evangelical denominations have complained it’s the opposite because of its focus on a white, middle-class male. But millions up and down the country sympathise with, if not identify with, the vicar.

Hollander’s charisma makes him likeable, both as a man of the cloth and a man of the people; a perfect match for the show’s own stance on religion. Those in the pews can share in his uncertainty. Those behind the altar can laugh with him (and at themselves). Those outside can agree with its negativity or be won over by it. It’s a series full of shortcomings, a showcase of divine imperfection – a quality that defines the UK more than anything else.

Britain is not a country of churchgoers any more. But if they don’t believe in God, they certainly believe in Rev.

Rev is available on BritBox, as part of a £5.99 monthly subscription.