Is Netflix’s reign over?

David Farnor | On 24, Apr 2022

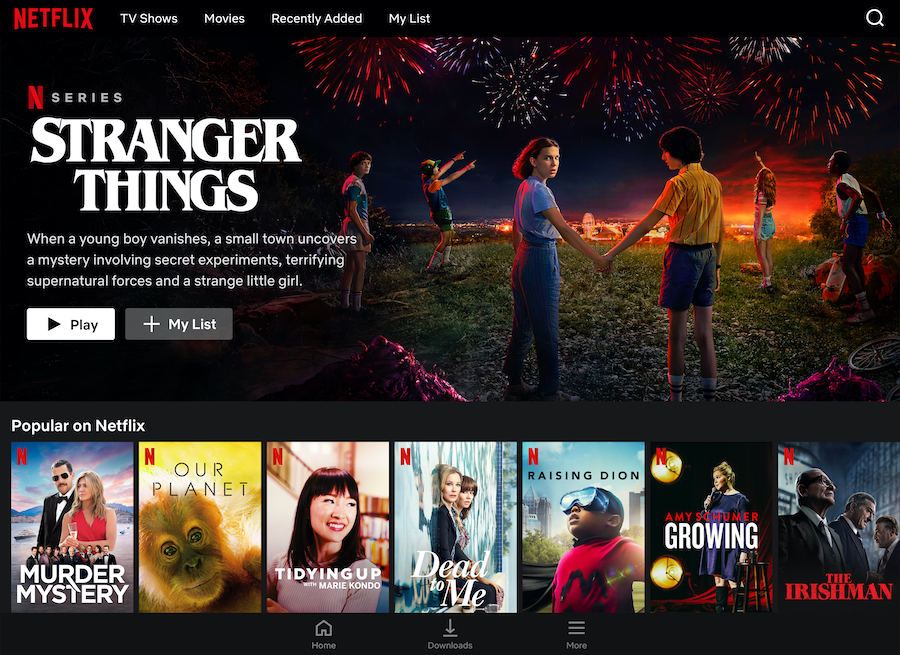

This week saw Netflix lose subscribers for the first time in 10 years. The streaming service saw its overall number of households drop by 200,000 in the first three months of this year, the first time it has seen a quarterly drop in net total customers since October 2011.

Share prices fell after the announcement, with the company admitting that it’s performing below its forecasts and expectations – and even forecast another drop in subscribers (by 2 million) over the coming quarter. All this has led many to wonder whether Netflix is down for the count, with the service about to collapse under the cumulative weight of its own market dominance.

Is this really the beginning of the end for Netflix?

Hefty headwinds

It’s certainly a formidable set of headwinds that the streaming giant is facing. The competition from rival services has surged in recent years, with the launch of HBO Max, Disney+, Peacock, Paramount+ and Apple TV+. Netflix has long enjoyed the first-mover advantage of a genuine disruptor, changing the way that we consume entertainment and sending ripples throughout the film and TV industry. Now, however, is the difficult stretch of time when the rest of the industry mounts its response, which means that audiences have more choice than ever to find entertainment elsewhere.

Many of those options are also cheaper, with Netflix raising its prices this year (not for the first time) in order to keep funding its operations and attempt to stay ahead of its rivals. All this is coming at a time when households are facing a serious financial squeeze, due to the cost-of-living crisis in the wake of Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Ukraine-Russia conflict. The latter has also seen Netflix cease operations in Russia, which cost it 700,000 subscribers.

Netflix was quick to try and highlight the trend of people sharing their Netflix accounts with other households as a factor in its challenging situation. It’s not a new problem for the company, but it’s now aiming to recoup any financial losses it can, either cracking down on that practice or encouraging households to pay a small extra fee to share their accounts with other households – it’s even been running a trial along those lines in several Latin American markets.

All this is happening at a time when Covid-19 restrictions have been lifting around the world, with people looking to return to normality. While thousands signed up to streaming services during lockdowns when staying indoors required entertainment, audiences are now looking to make the most of their chance of things returning to normal, away from their screens. (Kantar’s Entertainment on Demand study released last week found that 1.51m subscription vide-on-demand services were cancelled by households in the first quarter of 2022, with more than half a million cancellations attributed to saving money.)

Competition – for content

Netflix has previously welcomed or dismissed competition for eyeballs, with the broader philosophy that any subscription streaming service encourages the broader take-up of on-demand viewing compared to linear TV. More recently, it has recognised the impact of competition, but the consequences go deeper than just an alternative destination for films and TV.

The majority of new streaming services arriving on US and UK shores have their roots in much older entertainment forces, as the veterans of Hollywood respond to the relatively new contender on the block. They come with a valuable resource: IP. From HBO Max’s Warner library and Disney+ offering both Disney and Fox titles to Peacock’s NBC catalogue and the Paramount+ vault, they each come with a colossal collection of existing movies and shows, many of them with recognisable franchises that already hold some currency with audiences. Disney, for example, has made no secrecy of its strategy to mine the Star Wars and Marvel universes for new properties. Even Amazon, in response to this wave of legacy players, has acquired the whole of MGM to boost its own line-up of familiar titles.

Netflix, meanwhile, like Amazon Prime Video, has seen its catalogue lose a number of titles that were previously licensed from third parties. What began as an appealing aggregator of established favourites for one low-cost fee has had to transform its own business model, as the producers of those third party titles have reclaimed them for their own direct-to-consumer platforms.

Netflix, therefore, has upped its investment in original content, looking to produce and co-produce more and more titles itself so that it can hold titles exclusively and indefinitely. In this increasingly shifting landscape, one truth remains constant: content is king.

Quality vs quantity

Netflix’s rapid – and rapidly increasing – investment in original content initially gave the platform the edge against Amazon Prime Video and other rivals, giving it a foothold and library that’s already a formidable size. But the more it ups its quantity, the more the question of quality comes to bear, and Netflix right now is facing a serious test of its own model.

With new titles more effective at bringing in new audiences, it becomes more logical for Netflix to save money by not renewing (and prematurely cancelling) existing TV series that don’t generate enough of an ROI – especially as shows such as Stranger Things come with bigger price tags, due to its cast becoming more established stars, or production costs climb due to Covid-19 safety requirements and higher demand for crews and equipments. (Netflix’s high-profile, pricey deals with showrunners and other talent to develop programmes have also bought into the streaming hype in a manner reminiscent of the dotcom boom.)

What has therefore happened in recent years is that what once felt like a new, exciting disruptor operates more like a traditional media company. Perhaps the emotional connection Netflix had with audiences has dipped as a result. Perhaps the scale of consistent additions has led to things feeling less personalised – despite the company’s leading algorithm for pinpointing what people do like.

Asking for people to pay more each month requires them to feel like they’re getting more of precisely what they want, but by trying to appeal to everyone, Netflix has possibly lost some of its distinctive brand; it’s become not just a prestige TV producer or an international TV hub, but also a reality TV giant, an arthouse Oscars frontrunner, an investor in mid-budget films that lack traditional studio support, a supporter of controversial comedians and a purveyor of mainstream blockbuster movies. It’s also a mobile games developer, a graphic novel publisher and a podcast producer.

And then there’s the question of quantity. Even with the Covid-19 pandemic halting production for the past couple of years, slowing down the pace of original releases or resulting in periods where there weren’t many big hitters on the horizon, Netflix has continued to add new titles at a dizzying rate. However, with so many programmes and films landing in such quick succession, its focus on scale means that each show has a window of relevance that’s about a fortnight, or maybe a month – after that, the bubble of conversation moves on to the next new addition.

It’s at odds with the strength of on-demand entertainment in the first place – that, no matter when you sign up to a service, you have a library of original titles available at your fingertips, even those produced years ago. When you’re driven by marketing and promoting your service based on what’s new and coming soon, you condition audiences into shortening that shelf life.

The opposite approach is what has helped Apple TV+ enjoy such strong success in its early years. In addition to a consistent hit rate in terms of quality, Apple has amplified that by not rushing to build quantity. Driven by the need to keep subscribers with a drip-feed of new titles, it has dropped episodes of its original shows weekly – and that approach, reminiscent of the ongoing success of linear TV’s event programmes, such as Line of Duty, has had the effect of sustaining the conversation around its titles for longer than just a couple of weeks. It’s no coincidence that Netflix has decided to drop the final seasons of Grace & Frankie and Ozark in two parts this year, extending that conversational shelf life.

Down – but not out?

All these elements of Netflix’s diversifying and developing model – and the maturing, and fragmenting, nature of the streaming landscape – means that things are looking challenging for the company that started the SVOD ball rolling in the first place. The right decision for the company 5 years ago may not be the right decision for the company now.

It might seem surprising how bullish Netflix’s CEO Reed Hastings sounded in his letter to shareholders, in which he said: “Our plan is to reaccelerate our viewing and revenue growth by continuing to improve all aspects of Netflix – in particular, the quality of our programming and recommendations, which is what our members value most.” He also highlighted that Netflix’s programmes are “very popular globally” – the company’s recent move to publicise viewing figures is a conscious move to emphasise its size and reach compared to the competition.

And yet it’s easy to forget just how big Netflix is – it currently holds more than 220 million subscribers worldwide. While it considers trying to monetise account sharing, and maybe even introducing adverts for a lower-priced subscription, the company has a long way to fall before it actually crashes or burns. If it loses 2 million subscribers in the coming three months, for all the complex factors outlined above, it will still remain one of largest VOD players at the table, which will impact its revenue margins, but will mostly mean the company needs to reframe its definition of success away from constant expansion and growth.

In Russia, curiously, Netflix users have taken the step of suing the company for suspending its operations in the country, in an attempt to get it to reintroduce its service once more – a sign that Netflix’s appeal, in the face of the above, is still strong. And, with this weekend seeing the debut of three talked-about originals – new series Heartstopper and returning franchises Russian Doll and Selling Sunset – it seems likely that current reports of Netflix’s death have been greatly exaggerated. Netflix’s uncontested reign may soon be over but for now, the streaming giant is down but not out.

For more in-depth articles about the current VOD landscape, see our The State of Streaming series.