Bingeing on disillusion: Why we are more engaged with House of Cards than real politics

David Farnor | On 02, Apr 2015

“It’s mostly so I can pose for the photos,” Russian President Viktor Petrov tells Frank Underwood in House of Cards Season 3. They’re talking about surfing.

“Plays well with the young people,” he adds. “It’s important that they see their President has fun, doesn’t take himself too seriously.”

At the same time, in the less dramatic reality land, David Cameron was chatting to Woman & Home magazine. “I enjoy life [and] I’m fun,” he said of how he hoped his friends saw him.

It’s not the first time that a parallel has stuck out between Netflix’s drama and actual politics. It certainly won’t be the last. But away from the digs and the critiques, the show and the real world couldn’t be further apart.

We live in an age where a generation are disillusioned with politics and politicians. People, led by figures such as Russell Brand, campaign for other people not to bother voting at all. It’s an illogical argument I won’t go into here, but the point is this: disengaging from democracy has become, for some, a viable, justifiable option.

When Nick Clegg turned up at the 2010 general election, he energised a group of previously disenchanted voters: there was, he promised, another way. Soon after, though, he formed a coalition government with the Conservative Party, a move that has seen Liberal Democrat fans feeling betrayed like many others.

It’s a trend that is evident from the average turnouts for general elections. In 2010, it was 65.1%, down from the circa 80% that was once recorded in the 1950s.

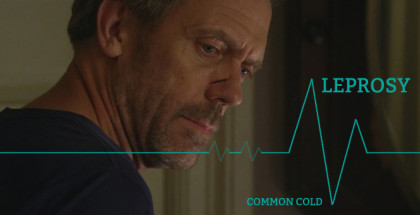

And yet we live in age where political drama has never been more in vogue. Years after The Thick of It and In the Loop, the BBC just blew its budget on an adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. Armando Ianucci has fled for the US, where Veep is about to start a fourth season. And, of course, Beau Willimon’s House of Cards just premiered its third run.

This is the wonderful paradox of today’s younger generation: in 2012’s local elections, just 31.3 per cent of people took 10 minutes to vote, but 1 per cent of Netflix subscribers in Europe gave up an entire weekend to watch all 13 episodes of House of Cards Season 2. We couldn’t care less about politics during the daytime, but we binge on it all night behind closed doors.

Even on social media, the juxtaposition is striking: Kevin Spacey has 3.9 million followers on Twitter, ahead of the official Prime Minister account on 3 million. David Cameron has 951,000 followers, ahead of House of Cards’ 512.9k, but Netflix UK has 214.5k, ahead of Labour (187k), the Conservative Party (142k) and the Liberal Democrats (86k).

The gap becomes even more bizarre when you consider the types of shows we enjoy watching: by and large, our fictional politicians are despicable, or at least untrustworthy, exactly the qualities that turn us off leaders in real life.

Clegg’s U-turn on various promises made during the 2010 election have left a swathe of voters unsure where to put their cross on the ballot. Underwood’s back-stabbing up the power chain, though, has made him one of the most celebrated anti-heroes of the modern age; a powerhouse of death stares and smiling deceit.

“I wouldn’t be here if I had a choice,” he tells the camera, while visiting his dad’s grave in Season 3, “but I have to do these sort of things now. Makes me seem more human. And you have to be a little human when you’re the President.”

That’s perhaps the crucial difference: he’s dishonest, but he’s honest about it.

It’s a characteristic that also defined Mark Rylance’s wonderfully engaging Cromwell in Wolf Hall, whose sideways glances left us in the loop, while everyone else fell victim to his cheating. Politics was a joke and, for once, we were in on it.

Even someone like the occasionally well-intentioned Selina Meyer in Veep is surrounded by an incompetent system that doesn’t work. And In the Loop, where the public perception of politicians matters significantly, concerns surrounding a toppling brick wall in a garden is laughable to MPs, while Steve Coogan’s consituent member is the butt of a joke.

In this time of scathing satire and bitter displeasure, The West Wing has never seemed more out of date. Aaron Sorkin’s highly watchable show is binged upon as a shot of hope from a bygone era. Now, we figure, it’s less about principles and more about who can pose better with a surfboard, an attitude that is reflected in the culture we produce; someone has to write House of Cards before we can watch it.

“Some say it’s really cynical,” Beau Willimon told the Wall Street Journal. “Others say it’s closer to the truth than you could ever want to imagine.”

Willimon should know to some extent: he worked for Senator Chuck Schumer’s 1998 campaign for Senate and for Howard Dean’s 2003 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Regardless of how truthful it is, we certainly want it to be: these kind of shows provide a feedback loop that we can use to power our own sense of dissatisfaction, Willimon included.

“There’s still an authenticity to the desire for power that I think all politicians have,” he added.

Last year, though, something happened that offered a lightning bolt to the political world: the Scottish independence referendum. Given a choice to change the system entirely, a whole country became engaged in a debate that could actually transform their future. With voting ages extended to those aged 16 and 17 – the ones most likely to have their heads buried in Netflix rather than party manifestoes – turnout was a staggering 84.59 per cent.

Even while the result was to maintain the status quo, it revealed a forgotten truth: people care about politics, if they’re given something to care about.

In the current TV landscape of negative politics, it takes a show from another country entirely to represent that possibility: Denmark’s Borgen, which has previously drawn half a million odd people on Saturday nights to watch a subtitled programme about the non-existent Birgitte Nyborg, an honest PM with an unabashed optmistic streak.

Over here, meanwhile, the dominance of downbeat democratic drama has even spread to the politicans themselves. David Cameron’s ideal night in? “Watching a good detective drama on TV, or House Of Cards,” he told Woman & Home.

“I wish things were that ruthlessly efficient,” Obama joked recently at a meeting with Silicon Valley types (including Netflix’s honcho Reed Hastings). “This guy’s getting a lot of stuff done.”

Are these statements true? Or just answers someone on their teams thought would play well with the public?

The fact that we question it at all says a lot – but not as much as them being possible fans too. If they buy into the portrayal of politics as a field of double-crosses and Machiavellian machinations, are they as jaded as the rest of us? If so, what hope does the system have of ever really changing and winning over this disillusioned generation?

3 million tuning into the Cameron vs. Miliband programme last Thursday on Channel 4 and Sky News suggests that there are still people out there interested in watching real politics on the TV. Tonight’s debate of all seven party leaders, meanwhile, is the kind of scene that Willimon, who scripted The Ides of March, could turn into gripping entertainment. Because, if anything, Season 3 of House of Cards confirms one continuing truth: Frank Underwood always plays well with the young people.

Photos: Nathaniel Bell for Netflix / Company Productions Ltd